Yesterday, we asked how low SPAC-led public debuts could go, and the answer was very close to zero. Some now-public companies that rode blank-check companies to the public markets have seen 90% or more of their value deleted.

It’s difficult to overstate how far some SPAC combinations have fallen.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on TechCrunch+ or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

The good news is that while the U.S. SPAC market went bananas last year, other countries’ public markets failed to generate as much blank-check corporate volume. Europe, for example, saw far fewer SPACs during the 2020-2021 boom than we tabulated in America. Does that mean that European startups dodged a bullet? Perhaps, but not to the degree that we may have first anticipated. Why? It comes down to company quality.

Today our exercise is simple. We’re going to look at some Q2 data from companies that went public in the United States via a SPAC to underscore just what a mess we’ve seen in America. Then, we’re going to chat about why we didn’t see this coming, and what the USA could learn from Europe. To work!

Today our exercise is simple. We’re going to look at some Q2 data from companies that went public in the United States via a SPAC to underscore just what a mess we’ve seen in America. Then, we’re going to chat about why we didn’t see this coming, and what the USA could learn from Europe. To work!

Caveat emptor

The obvious root of the SPAC mess is greed. SPACs created a chance for huge financial rewards for their backers, which led to a greater number of them being launched into the market. Backed by equally yield-seeking capital, they had to find something to buy or leave their potential upside unrealized. Thus, we got a bunch of companies that wanted capital as much as SPACs wanted to spend it. So they linked up and put a bunch of eventual messes into the hands of public-market investors.

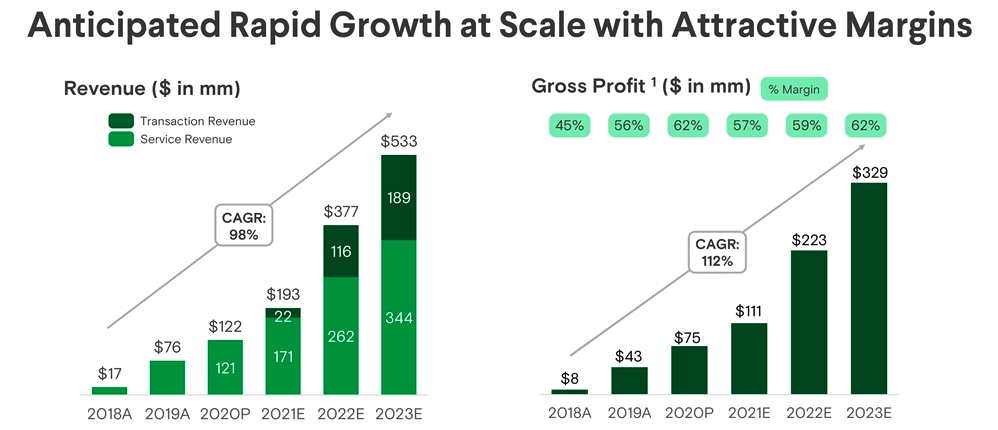

Perhaps only greed could have made those charts in SPAC decks make sense. Dave, to pick on one of the recent SPAC deals we’ve tracked, posted the following brace of charts in its investor deck last June:

Image Credits: Dave investor deck

And now, here’s Dave’s CFO during its latest earnings call, which marked the second quarter of its fiscal year, i.e., calendar 2022:

[W]e’re updating our revenue guidance, which reflects performance in the first half of the year combined with our expectations for the second half of the year taking into account our proportionately lower level of marketing spend. We now expect total non-GAAP operating revenues to be between $200 million and $215 million for the year, narrowing the range from $200 million to $230 million that we gave on our Q1 call.

Not to overdo it with the math, but it’s worth pointing out here that $200 million to $215 million in total estimated 2022 top line is less than the gross profit that the company projected for the period in its investor deck.

And Dave is hardly alone. Bird, the scooter company, projected 1.9 rides per scooter per day (average) in 2022, leading to 76 million rides in the year, $447 million worth of gross transaction volume, revenue of $401 million and a $28 million adjusted EBITDA loss.

In the first half of the year, however, Bird saw just 21.8 million rides generated from 1.3 rides per day per scooter (average), gross transaction volume of just $129.1 million, revenue of $114.6 million and adjusted EBITDA loss of $56.0 million in the six-month period. Those figures do not appear on track to reach projections.

But charts that go up and to the right look great, yeah? Sure. But they belong in Series A decks and not public company merger docs. Sadly, this isn’t even the first time that we’ve had a SPAC boom. And the last one wasn’t even two decades ago.

Have other markets that failed to draw as many SPACs managed to launch the lucky ones in the end?

Dodged bullet?

Things have turned so sour for SPACs that it leaves us with a question: Why did anyone think that this was a good idea again? And when we say “again,” it’s because this isn’t the first time SPACs failed to deliver. Back in 2009, Reuters reported on blank-check companies “which have raised billions but not yet made the acquisitions that money is supposed to be spent on.”

We would love to hear the most vocal SPAC advocates comment on this déjà vu, but unfortunately, they have been unusually silent. What will happen when SPACs fail to find targets remains to be seen, but in the meantime, we can turn to retrospective data and regional comparisons.

According to reports from law firm White & Case, de-SPAC M&A deal value declined significantly in the U.S., dropping from $231.31 billion during H1 2021 to $26.29 billion in H1 2022. That same metric also plummeted in Europe, from $42.53 billion to $20.86 billion. But as the numbers show, Europe’s SPAC market was falling from much lower heights.

It’s not just in deal volume that Europe’s approach to blank-check vehicles differed from the U.S. SPAC craze. As The Exchange noted when Deezer went public in France, “the long-term incentives of blank-check companies and later investors are better aligned in European SPACs than in their U.S. counterparts.”

Aside from less misalignment, a key difference between American and European SPACs is that the latter haven’t typically been open to retail investors. Deezer, for instance, is listed on the professional segment of Euronext Paris, which is restricted.

Although Deezer saw its stock crash on its first day of trading and lost its unicorn market cap, that isn’t particularly bad for a SPAC. With this in mind, it would be fair to say that European retail investors dodged a bullet — Deezer was one of its few SPACs. But French financial outlet Le Revenu suggests investors might want to be picky and cautious even when participating in traditional IPOs, “which are far from always winning [investments] for new shareholders.”

Disappointing public listings aren’t specific to continental Europe. In a spicy chart titled “Top of the Flops,” Bloomberg recapped how several flagship London listings “have crashed since going public in recent years.”

Another way to look at SPACs is to see them as yet another IPO varietal, and the 2022 vintage doesn’t look good for anybody. The dearth of public exits is because bankers have moved their attention from public to private markets. And as for SPACs? One advisory firm pivoted into helping them shut down.

In this context, it feels slightly out of sync that regulators and stock markets are still focusing on making rules more amiable for unicorns wanting to go public. This probably can’t hurt, but we doubt that it will matter much in determining when IPOs will return. We saved the good news for last: These could come back with a bang, and sooner than later.