Coinbase utterly crushed its most recent quarter. Its results came in far ahead of street expectations, with the U.S. crypto exchange posting net revenues of $2.49 billion, net income of $840 million and adjusted EBITDA of $1.21 billion. In comparative terms, Coinbase’s Q4 2021 results bested its full-year 2020 results by a huge margin.

And yet, Coinbase shares are up just over a point in pre-market trading, and the company is worth around $70 per share less than its direct listing reference price; Coinbase is also down around 57% from its recent highs. The company’s incredibly profitable 2021 — net income of $3.62 billion from $7.35 billion in total net revenue — has led to a less valuable Coinbase, at least according to recent trading.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on TechCrunch+ or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

For a company worth $8 billion back in 2018, a 2022 market cap of $47 billion is far from a failure. But it’s still a fraction of what Coinbase was worth just months ago and around the time of its public-market debut.

No one knows what anything is worth.

It’s a theme we’ve touched on before, but a recent repricing of the entire technology market makes the point once again.

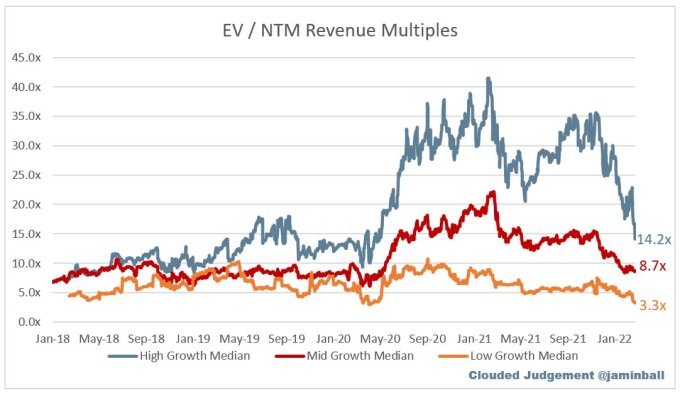

There’s more to the matter than just Coinbase, however, even though it’s curious that it appears to be valued on a profit multiple today more than a revenue multiple. The surge in SaaS valuations has come back to Earth, with Altimeter Capital’s Jamin Ball reporting this week that “high growth software revenue multiples have now normalized back to where they were pre-covid for the first time since the pandemic started.”

The former venture capitalist also writes that the fastest-growing cohort has performed “worse than low and medium growth software” companies this year. It’s upside-down season in terms of what software companies are worth, with the growth premiums falling sharply.

I think this is why we’re seeing reports that the late-stage capital cannons of 2021 are pulling back from such deals. Tiger, D1 and others were betting that they could flood the middle- and later-stage software markets with capital — and reap the rewards when their portfolios followed an open IPO window into welcoming public markets. If the IPO window had stayed open, and if software valuations hadn’t tumbled so sharply in just a few months, the strategy could have been incredibly accretive in the near term.

The opposite happened, however. So where does that leave late-stage startups? In trouble, I reckon.

Are they really in trouble, or are you just being pessimistic on a Friday, Alex?

I hear you, but consider the following chart from Ball:

Image Credits: Jamin Ball. Used with permission.

You can see the period of time in which high-growth software multiples surged into the 40x range among public companies. And now it’s less than half of that.

Furthermore, PitchBook data concerning the U.S. venture capital market in 2021 indicates that average valuations for late-stage startups shot to $753.3 million in 2021, up from around $400 million or so in 2020. Up went the startup prices, and then down went the market. The rising gap between them is a chasm that we might label something akin to “here there be monsters” on a map.

But all of that is just numbers and charts and other bullshit. Let’s engage in a little thought experiment.

Let’s say you run a software company that raised money in 2021. Market conditions were hot and investors were falling over themselves to get into deals, and so you raised, let’s say, $100 million at a $900 million pre-money valuation. That made your company a post-money unicorn. And thanks to high public multiples, you snagged the capital with just $15 million in ARR. You figured that you could grow into the number by the time you needed to raise again, keeping the game going until you exit. Congrats.

But now the market isn’t paying 66x ARR multiples for software startups — unless they are among the very best. So your plan to reach $30 million ARR and raise at a flat multiple and roughly $2 billion valuation in your next round is now harder. How much harder? Let’s say you can still raise that next round at a 33x multiple, or half. (Given the above chart, that might be a generous discount, frankly.) You’ll need $60 million worth of ARR now to get the price you wanted in your next round, twice as much.

So you don’t get the price you want, I think. Why? Because the compression of valuation multiples consumes the result of revenue growth when we consider future value; if multiples compress, revenue growth can become water-treading from a valuation perspective.

For late-stage startups that raised at high prices in the last year or two, if their growth rates stay strong, I reckon many can attract more capital at flat-ish prices this year, pending changes to market conditions, of course. But if growth is decelerating at a late-stage unicorn at anything close to a material clip, it’s going to be hard to do so. Everyone can run the math on what slowing growth and cash burn are worth on the public markets, and it’s a very, very different number than it was last year.