Amid the chaos of the COVID-19 pandemic and the murky path to profitability for shared electric micromobility, an increasing number of companies have turned to subscriptions. It’s a business model that some founders and investors argue hits the profit center sweet spot — an approach that appeals to customers who are wary of sharing as well as paying upfront to own a scooter or e-bike, all while minimizing overhead costs and depreciation of assets.

Many investors think the subscription model will broaden the micromobility market, positioning it essentially as a software-as-a-service business, which achieves a higher multiple.

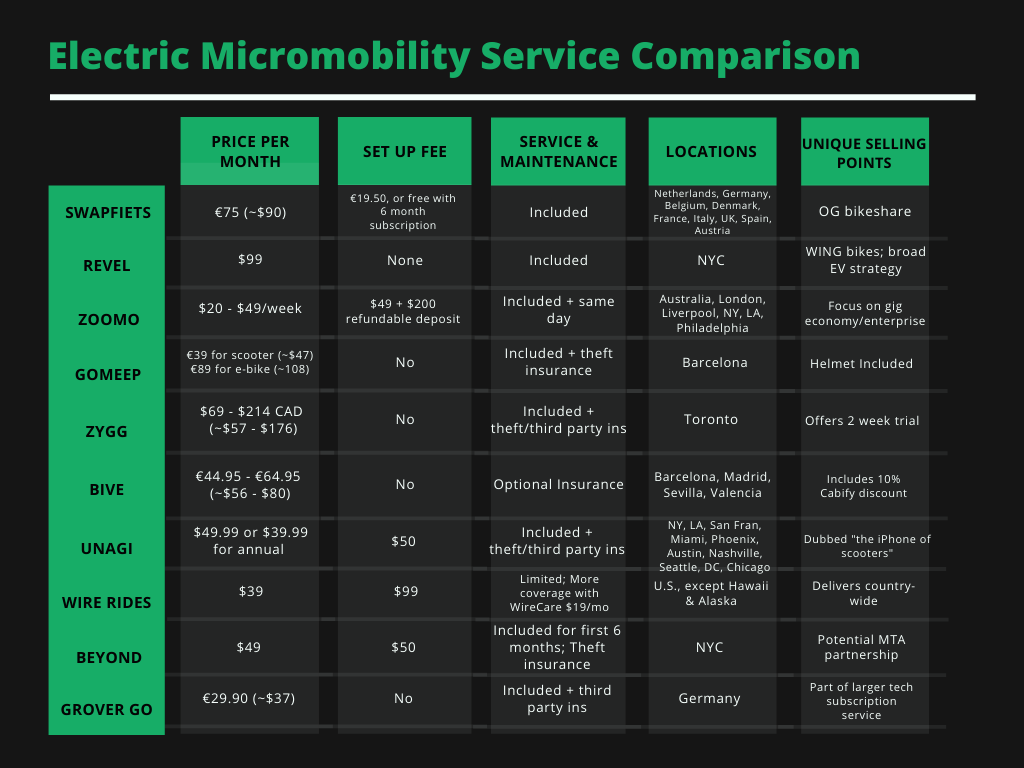

Across the United States, Europe, some of Canada and at least eight Middle Eastern cities, existing mobility companies are adding a subscription business line to their repertoire, and entirely new companies are being formed on the basis of the hardware-as-a-service model. But will this new playbook push the unit economics of micromobility in a positive direction? And what will determine which companies win at the subscription game?

In general, subscriptions for everything from groceries and streaming video to exercise equipment and clothing are on an upward slope. Subscription businesses are expected to grow at a rate of 30% this year, according to a 2021 study by digital services monetization company Telecoming.

Micromobility vendors keen to follow other industries into this model are focused on several factors, according to experts following the industry: the ease of scaling, return on investment and cost-per-mile to operate.

“Subscription services for a single vehicle are far more interesting and scalable than the subscription model that was trialed by the shared mobility services,” Oliver Bruce, angel investor and co-host of the Micromobility Podcast with Horace Dediu, told TechCrunch. “The cost per kilometer is just an order of magnitude smaller, and it’s not constrained by citywide caps.”

Shawn Carolan, managing director at Menlo Ventures, is also bullish on the micromobility subscription model because it makes more sense for the consumer, as most people will prefer to pay a low monthly fee rather than a higher upfront fee.

“The best customers are repeat customers, commuters or local neighborhood trips,” Carolan said. “Repeatedly paying per ride is both expensive and cognitively taxing. People want low friction in transportation. Getting from here to there shouldn’t require a lot of thought.”

The key players: E-bikes

Bird and Lime might dominate the shared micromobility space, but they’re not leading the subscription market, largely because their bikes and scooters are built to be heavier and more robust in order to handle city usage. Their operating systems are also designed to manage fleets and keep the vehicles in specific territories within a city. Bird and Spin have announced intentions to offer subscriptions, but so far there’s only been a chance to sign up for a waitlist.

Meanwhile, subscription services tend to offer lighter-weight vehicles that can be carried up flights of stairs or even folded down.

Swapfiets, the bike-sharing company with the distinctive blue front wheel, is one of the pioneers in the world of bike-sharing. In 2015, Richard Burger, Martijn Obers and Dirk de Bruijn started the Dutch company as university students in Delft when they realized that owning a bike could be somewhat of a hassle. The Netherlands is renowned for having more bicycles than people, but that doesn’t make it any easier to buy, sell and maintain them, especially with such high fees at bike shops.

“We asked how we could shift this and get only benefits from using a bike to go from A to B and not have all this hassle,” Burger told TechCrunch. “And for us, the subscription model was really the realization that would fix that.”

Swapfiets is now operating in nine countries and roughly 60 cities throughout Europe and has expanded from regular bicycles to e-bikes. It has even launched some pilots for e-scooters and e-mopeds in certain cities.

Dockless shared e-moped company Revel announced in February that it would add an e-bike subscription to its business. Customers interested in subscribing to its pedal-assist WING bikes have been relegated to a waitlist because demand is outpacing supply, the company said. For now, Revel’s e-bikes business is limited to customers in New York City, with the exception of Staten Island.

Other notable companies selling subscriptions include BuzzBike in London, which only rents out pushbikes; Dance in Berlin; Bive in Madrid, Valencia and Sevilla; and Zygg in Toronto. Australian-born Zoomo, which just secured $12 million in an interim capital raise, has geared its subscriptions more toward gig economy workers and enterprise delivery fleets. With these new funds, it’s looking to expand its consumer offerings, as well.

The key players: E-scooters

In the world of e-scooter subscriptions, Unagi has pushed to be the frontrunner. The startup was launched in 2018 by former Beats Music CEO and MOG co-founder David Hyman.

“We were looking at other hardware-as-a-service plays, asking ourselves if there was a market for subscriptions around e-scooters,” Hyman said. “It started as a hunch thinking people would want a Netflix-like experience without commitment.”

Unagi announced in March 2021 a $10.5 million funding round, which it used to expand its subscription service to Austin, Miami, Nashville, Phoenix, San Francisco and Seattle, as well as further entrenching itself in the New York and Los Angeles metropolitan regions. The company also sells its foldable kick scooters. Part of its business model is to repurpose returned scooters and use them for subscriptions.

Beyond, formerly Brooklyness, raised $1.8 million in seed funding last year. It has a similar ethos to Unagi in that design and high-quality parts are of utmost importance to ensure a premium vehicle with a longer life cycle. Both companies design all components of their vehicles and assemble them in-house.

“Our vehicles are designed so they’re super easy to maintain; all the wearable components of the vehicle are easy to access, and we reduce the [number] of components to the minimum,” Beyond founder and CEO Manuel Saez said. “Our thinking is that service or maintenance will be very efficient for us, and in that way, we don’t have a high cost associated with running the service.”

Beyond also sells its scooters, and Saez said if someone has been subscribing monthly and decides they want to buy their scooter, Beyond will put the money they’ve already spent toward the sale of the scooter.

Similarly, Wire Rides, founded in 2018, offers both subscription and sale of its Ohm e-scooter. It appears to be one of the only companies that delivers to 48 states in the country.

“We actually probably have more customers outside of metro areas than inside metro areas,” said co-founder Nick Drombosky, adding that before COVID, they also had college students who would subscribe to scooters for a semester at a time.

In 2019, Grover, the German consumer tech subscription service, launched a monthly e-scooter subscription service called GroverGo. It currently offers its own branded e-scooter, the Grover Rush, but it can get subscribers situated with any number of major brand-name vehicles from the likes of Segway-Ninebot, Xiaomi and iconBIT.

Abu Dhabi-based e-scooter operator Fenix, which recently launched a 10-minute food delivery service via its shared scooters, also has a subscription business called MyFENIX which is active in eight cities across three countries.

Image Credits: Rebecca Bellan / TechCrunch

Who’s investing

The field of VCs investing in the idea — and business — of micromobility subscriptions is small and growing.

Maniv Mobility, an Israeli VC that specializes in early-stage mobility companies, is one of the more bullish of the firms on subscriptions. The VC participated in rounds for Zoomo, Revel and Fenix.

“There are just so many variables because there’s different hardware and there’s different pricing models,” said Michael Granoff, founder and managing partner at Maniv Mobility. “I think the numbers can certainly work, and we’ve seen it a bit alongside free-floating vehicles and the ownership model. We haven’t seen it at scale, though, so I can’t say whether it would work as a standalone business.”

Narrative Fund and Brooklyn Bridge Ventures co-led Beyond’s seed round that was announced in December 2020. Social Capital, SOSV and Spacestation, a New York multimedia company, also participated.

Menlo Ventures, which has invested in tech wins like Uber, Poshmark and Betterment, led Unagi’s seed round. The firm made a bet that customers would take better care of a high-quality scooter they get to “own” for a time, leading to a longer lifetime for the hardware, Carolan told TechCrunch.

“That ultimately translates to higher lifetime value (LTV) per scooter,” Carolan said. “This stands in contrast to the shared-scooter model that typically includes the risk of damage and theft in the price. That cost that traditional scoot-share players incur either gets handed to the consumer via higher price-per-mile (discouraging some riders) and also shrinks the LTV per scooter.”

Many investors think the subscription model will broaden the micromobility market, positioning it essentially as a software-as-a-service business, which achieves a higher multiple, according to Carolan.

Other investors have put capital toward startups pushing subscriptions, including Dance’s backers HV Capital and BlueYard, which participated in the company’s €15 million Series A last October, and Ponooc, which has a majority share in Swapfiets. Ponooc would not disclose funding amounts.

What’s next?

The business of selling micromobility subscriptions is still fresh, as is the usage of electric scooters and bikes. Experts have forecast growth on both fronts. Subscriptions are likely to make up a third of the micromobility market, with sales and rideshares taking up the other two pieces of the pie, according to a joint study by Unagi and UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business.

Meanwhile, outright sales of e-bikes are also projected to rise, leading some companies to try the dual sales and subscription approach. Electric bike sales grew by 145% in the U.S. from 2019 to 2020. In Europe, industry experts have forecast the number of e-bikes sold each year could increase from 3.7 million in 2018 to 17 million in 2030.

Simply offering subscriptions doesn’t guarantee a profitable enterprise. Company founders told TechCrunch that diversification, data and analytics, and customer retention are areas being prioritized.

“In order to scale to the level that we want to be, we will need to get a lot better at profiling people and being able to target people specifically,” said Saez of Beyond. “We haven’t had that problem so far, as it’s been a lot of referrals. That’s been key for us, and what we’ve been doing is building all the tools to make that easy for them.”

Beyond picks up its most valuable data by asking its customers about what they do and how they use the scooters, Saez said.

“Seventy percent of our customer base is what we call ‘blue collar,’ so nonspecialized trade, and they use it mainly for commuting,” he said. “Those are people that live in the outer borders that used to walk 20 minutes to the train. Now that just is a quick scoot and they get half an hour to an hour back in their lives.”

Customer service and maintenance plans are among the hot opportunities for scooter- and e-bike-adjacent software companies to enter into the market as they’re key to retaining existing subscribers. Some startups such as Beyond are taking those software efforts in-house.

Carolan was of a similar mind. With any subscription business that uses an expensive asset, it’s imperative to dial in the unit economics, and that means minimizing fraud and theft and handling repairs and servicing, he said. Keeping up will require continuous improvement, but Carolan said it’s well within the scope of available technologies.

“The job to be done is reliability,” Bruce said. “Maintenance and repairs is still a nascent sector, but for people who want to have a reliable option for travel and don’t know or care about how to maintain their brakes or gears, it’s a really good option. Proper servicing will open up micromobility to a far wider group, especially when paired to safe infrastructure and favorable transport policies.”