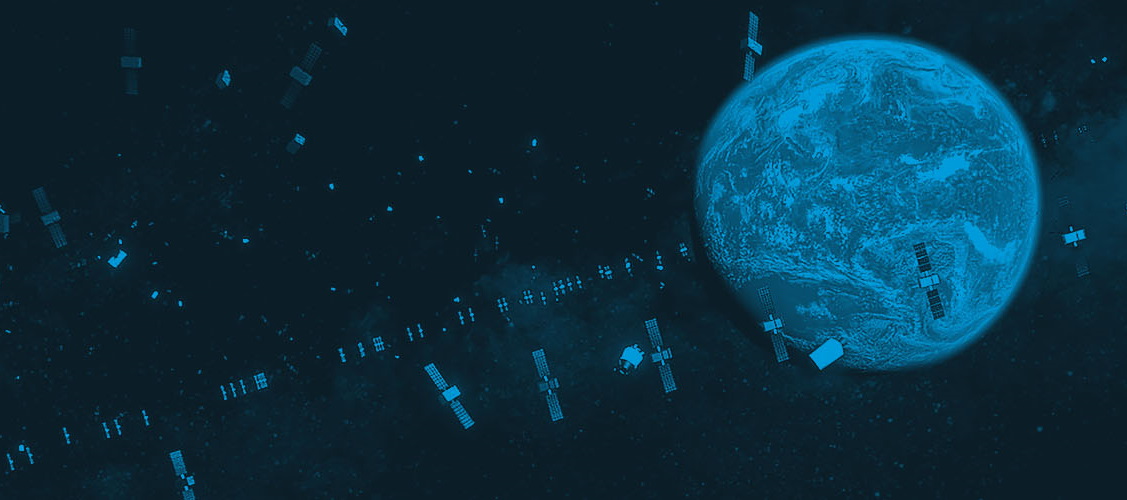

The space economy in the last few years has been in large part driven by the increasing cadence and reliability of launch services, and while that market will continue to grow, the new economy enabled by those launches is only just beginning to take off. If you thought the launch boom was big, just wait for when it combines with the private satellite boom.

The consensus among experts, company leadership and investors in the space sector is that launch has commanded an outsize share of both money and attention, both because it’s so broadly appealing and because it was a prerequisite to any kind of space-based economy.

If you thought the launch boom was big, just wait for when it combines with the private satellite boom.

But as we’ve seen over the last year, and as is expected to be further demonstrated in 2021, the launch industry is moving from investor-subsidized R&D and testing to a full-fledged service economy.

“To date the launch industry has received 47% of the industry’s venture capital, even though it’s less than 2% of the global space economy,” said Meagan Crawford, managing partner at SpaceFund, at TC Sessions: Space last week. “We feel like that’s a problem that’s been solved, or that’s being solved. What we want to know is what is enabled by launch, right? What are the new things that can happen now, the new business models that close today that didn’t close three years ago when launch was not as frequent, reliable and low cost?”

Within the launch industry this view seems to be shared, even at companies that have yet to take a payload to orbit. Their focus is not just on proving their launch vehicle can do it, but taking their place in a massively supply-constrained (on the launch side) market by differentiating and appealing to new business models. That involves far more than building a working rocket.

“It’s not just about mass to orbit,” said Mandy Vaughn, president of VOX Space. “It’s about all those other elements of, how can we react quickly? How can we design and produce something quickly, as well as deploy that capability, maybe in a unique way from an unexpected location? In terms of the investment landscape, it’s not just about the technology of one rocket, or what’s your ISP [in-space propulsion] compared to another’s. It really is, what is the complete vertical infrastructure and business model beyond just mass to orbit?”

Tim Ellis, founder and CEO of Relativity Space, which will launch its first fully 3D-printed rocket in 2021, concurred in a conversation we had outside the conference.

“The thing we’re watching closest is not, while it’s fun, the different launch providers, but how many new satellite companies are getting to orbit,” he said. “We’re still seeing the market growing faster than the launch vehicle companies have been able to keep up with.”

Another of those new launch providers is Astra, which just had its first successful test launch last week and plans to serve customers looking for a quicker, cheaper ride to space.

Image Credits: Astra/John Kraus (opens in a new window)

“On the demand side, you see literally thousands and thousands of satellites that need to go up. At some point we may see supply and demand come into balance, or be imbalanced in a way that we need fewer of these companies to do it. But not right now,” said Chris Kemp, CEO and founder of Astra, in a panel.

“A few years ago we had a couple of startups that were buying secondary payload opportunities on large rockets,” he continued. “But there’s a new groundswell of companies that are finally getting out of that development phase, and they’re starting to buy for their constellation deployments. I think we have now two dozen launches on manifests representing over 100 spacecraft.”

One of the largest of those companies is certainly Amazon, which is beginning the massive effort of putting thousands of spacecraft into orbit for its proposed Kuiper communications constellation. The question for Amazon, and for Dave Limp, who heads the project, is not simply one of securing enough rides to orbit but of establishing an entirely new mass-manufacturing and distribution process for satellites.

“At constellations of this size, it’s not aerospace as usual. You have to kind of reinvent aerospace,” he told TechCrunch’s Darrell Etherington. “Because we have to produce, you know, not a satellite a year or a satellite every two years, but a satellite every couple days, or maybe even every day depending on how the launch capacity looks. So that takes reinvention of not only how you think about and design the satellite itself, but how you’re going to manufacture it, how you’re going to transport it, how you’re going to get it into a fairing on different types of launch vehicles and get it into space.”

“This does not come with a small price tag,” he added. “We’ve already committed $10 billion to this effort — and it may require more.”

There are several ways in which the industry must advance in order to accommodate such enormous ambitions. One is simply by organizing the information out there better, said Tim Ellis.

“I still haven’t seen great data where someone looks at the number of satellites that needs to be launched, total mass, launch opportunities, etc. — the supply and demand mapping for launch and spacecraft markets,” he said. Some of this is publicly available, such as through FCC filings, but some is fuzzy, secret or otherwise inaccessible.

If launch is to exist as a logistics solution, then like other logistics industries the data needs to be available for people to make informed assumptions and long-term plans. As VOX Space’s Vaughn explained, there needs to be more cooperation within the industry at the business level for that to happen.

“What I would like to see is just that it’s not necessarily a special niche thing, but just that the industry as a whole just has this kind of inherent flexibility, that payloads can easily move or change their schedule,” she said. “Rather than rideshare being this unique niche thing, it just kind of becomes normal, we can change our airline reservations at the last minute. if we’ve got a ride, and it’s going to the place that you’d like to go, how can we make that easy and transferable across the industry?”

This has occurred, of course, just not quite as easily as Vaughn suggests it ought to be. Capella’s recent launch with Rocket Lab was originally scheduled to go up with SpaceX. It’s not so long since the days when swapping providers like that wouldn’t be possible at all.

One aspect of the industry that may be at an inflection point is the lifespan of satellites, and whether they can be refueled, repaired and refitted. As Astra’s Kemp noted, “You wouldn’t service a satellite if it costs you as much as the cost of the satellite to service it. But if you can service it or upgrade it at a fraction of the cost, that would be really attractive to all parties.”

In a panel focusing on this very possibility, I spoke with leaders at three companies planning orbital servicing experiments in 2021. The general idea is to show that the practice is no longer a mere possibility but could be a serious consideration for any spacecraft being designed today.

“If you can launch smaller subsystems payloads and whatnot, and then be able to assemble things in space, maybe change out a certain aspect of what that satellite is doing … Why can’t we go up and actually change out a power subsystem, change out a camera mechanism, a computing element, whatever the case may be?” asked Lucy Condakchian, GM of robotics at Maxar Technologies.

Her company is working with NASA on OSAM-1, a sort of omnibus orbital servicing mission that will show off on-orbit refueling, assembly of a multipart antenna using a robotic arm (Condakchian’s team specializes in this, having supplied multiple Mars landers), and 3D printing of a long composite beam.

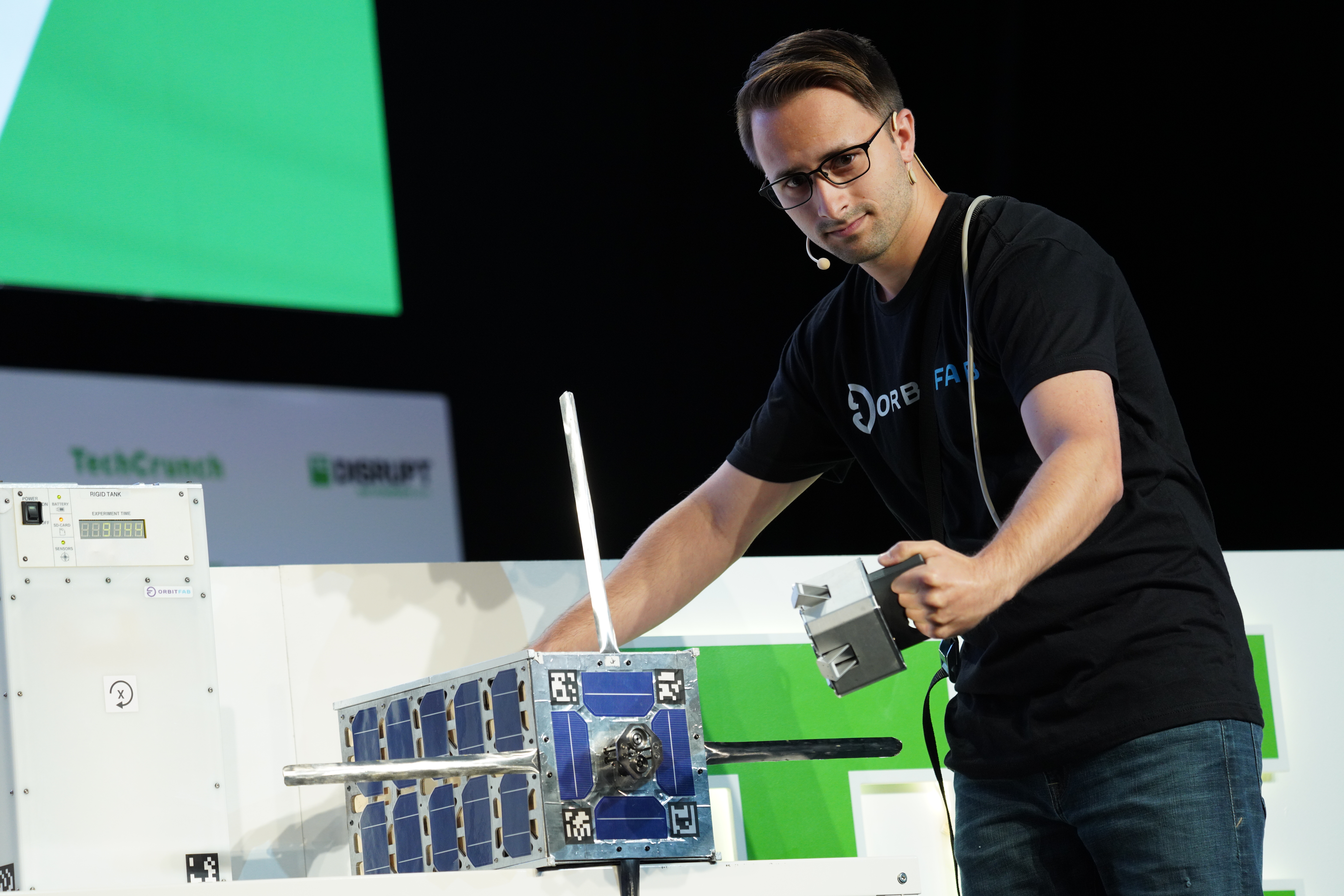

Daniel Faber, whose company Orbit Fab, was a finalist at Disrupt’s Startup Battlefield last year, aims to standardize a new port for servicing and refueling spacecraft. Does it make sense for a cheap cubesat that will only be up there for 3-4 years? Maybe not, but satellites in both low and geosynchronous orbits are often investments meant to last a decade or more — especially if they can be repaired or refueled.

“The GEO life extension market, that’s a market that exists today — it’s real, there’s a need right now,” he said, but the better indicator of opportunity is, as Ellis pointed out, the proliferation of new customers. “If there’s really a way to tell that there’s value to be created in a new capital intensive ecosystem it is the velocity of new entrants getting in.”

“It’s backed up not just by a technology shift where these robotics are now feasible — complex, but feasible — but also by a market paradigm shift where we can see that everybody’s accepting that this is the future, they’re considering building it in. And as it’s become a reality, it’s getting built into the business models … that’s then got the investors following and looking for those opportunities. It’s all come together in really just the last five years.”

One beneficiary of investor confidence is certainly AstroScale, which has attracted $291 million in funding, $51 million of that in a recent E round. Ron Lopez, president of the company’s U.S. division, said that the company’s approach to on-orbit inspection — and if necessary, de-orbiting — reflects the concern of multiple stakeholders.

“There’s any number of different use cases for this kind of capability,” he said. “Insurance claims if there’s an anomaly on a satellite and it needs to be determined what it was that happened, etc., or space situational awareness. Of course, we know that this is a big concern for everybody with the increasing number of objects in space — understanding what’s where, doing what, and is it a threat to other objects in space are all very important.”

Already a major partnership has been struck between SpaceX and LeoLabs, which offers high-fidelity tracking of satellites and debris. Ellis predicts that a robust intersatellite communication system should be a priority going forward.

“Think of creating the internet at first, like laying fiber, setting up network switches, basic compute functions,” he said. “It was super simple. but over time it has become super complex, with all kinds of niches and services that are feeding a huge market. I think there are opportunities in that, whether it’s ground stations, space situational awareness like orbital debris — those are starting to be opportunities as the ecosystem starts to scale. It’s not as sexy, but it plays a huge role, and I think there will be some pretty large companies that will get formed, especially on the ground.”

That last note, “especially on the ground,” is an important one. The opportunities on the ground are multiplying as the industry matures — and many of them can be addressed purely in terms of data and software, providing space for fast-moving companies in a mostly slow-moving sector.