A new project called Keen is launching today from Google’s in-house incubator for new ideas, Area 120, to help users track their interests. The app is like a modern rethinking of the Google Alerts service, which allows users to monitor the web for specific content. Except instead of sending emails about new Google Search results, Keen leverages a combination of machine learning techniques and human collaboration to help users curate content around a topic.

Each individual area of interest is called a “keen” — a word often used to reference someone with an intellectual quickness.

The idea for the project came about after co-founder C.J. Adams realized he was spending too much time on his phone mindlessly browsing feeds and images to fill his downtime. He realized that time could be better spent learning more about a topic he was interested in — perhaps something he always wanted to research more or a skill he wanted to learn.

To explore this idea, he and four colleagues at Google worked in collaboration with the company’s People and AI Research (PAIR) team, which focuses on human-centered machine learning, to create what has now become Keen.

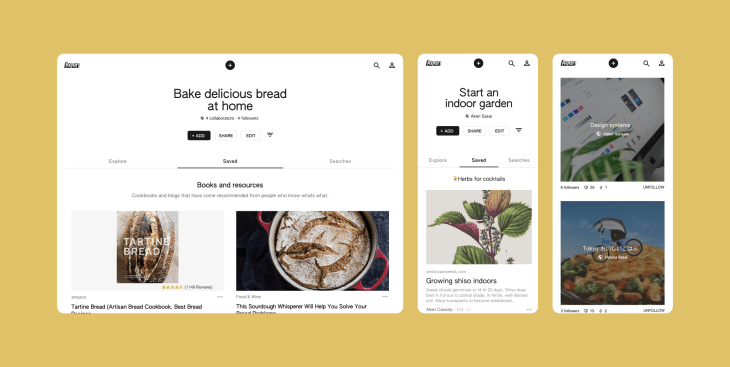

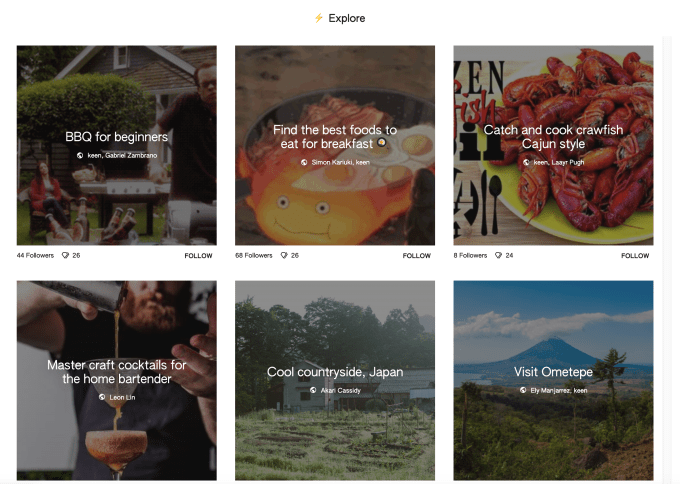

To use Keen, which is available both on the web and on Android, you first sign in with your Google account and enter in a topic you want to research. This could be something like learning to bake bread, bird watching or learning about typography, suggests Adams in an announcement about the new project.

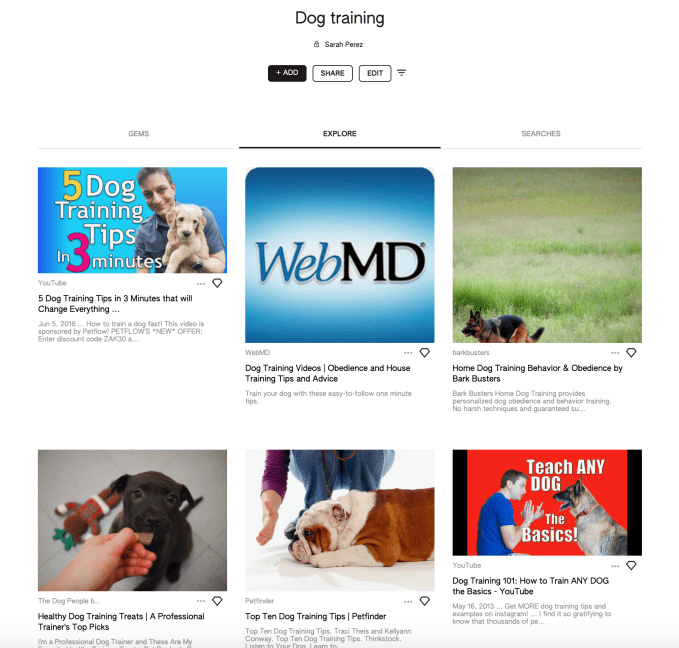

Keen may suggest additional topics related to your interest. For example, type in “dog training” and Keen could suggest “dog training classes,” “dog training books,” “dog training tricks,” “dog training videos” and so on. Click on the suggestions you want to track and your keen is created.

When you return to the keen, you’ll find a pinboard of images linking to web content that matches your interests. In the dog training example, Keen found articles and YouTube videos, blog posts featuring curated lists of resources, an Amazon link to dog training treats and more.

For every collection, the service uses Google Search and machine learning to help discover more content related to the given interest. The more you add to a keen and organize it, the better these recommendations become.

It’s like an automated version of Pinterest, in fact.

Once a “keen” is created, you can then optionally add to the collection, remove items you don’t want and share the Keen with others to allow them to also add content. The resulting collection can be either public or private. Keen can also email you alerts when new content is available.

Google, to some extent, already uses similar techniques to power its news feed in the Google app. The feed, in that case, uses a combination of items from your Google Search history and topics you explicitly follow to find news and information it can deliver to you directly on the Google app’s home screen. Keen, however, isn’t tapping into your search history. It’s only pulling content based on interests you directly input.

And unlike the news feed, a keen isn’t necessarily focused only on recent items. Any sort of informative, helpful information about the topic can be returned. This can include relevant websites, events, videos and even products.

But as a Google project — and one that asks you to authenticate with your Google login — the data it collects is shared with Google. Keen, like anything else at Google, is governed by the company’s privacy policy.

Though Keen today is a small project inside a big company, it represents another step toward the continued personalization of the web. Tech companies long since realized that connecting users with more of the content that interests them increases their engagement, session length, retention and their positive sentiment for the service in question.

But personalization, unchecked, limits users’ exposure to new information or dissenting opinions. It narrows a person’s worldview. It creates filter bubbles and echo chambers. Algorithmic-based recommendations can send users searching for fringe content further down dangerous rabbit holes, even radicalizing them over time. And in extreme cases, radicalized individuals become terrorists.

Keen would be a better idea if it were pairing machine-learning with topical experts. But it doesn’t add a layer of human expertise on top of its tech, beyond those friends and family you specifically invite to collaborate, if you even choose to. That leaves the system wanting for better human editorial curation, and perhaps the need for a narrower focus to start.