Earlier this month, Canalys used the word “freefall” to describe its latest reporting. Global shipments fell 6.8% year over year. At 313.9 million, they were at their lowest level in nearly half a decade.

Of the major players, Apple was easily the hardest hit, falling 23.2% year over year. The firm says that’s the “largest single-quarter decline in the history of the iPhone.” And it’s not an anomaly, either. It’s part of a continued slide for the company, seen most recently in its Q1 earnings, which found the handset once again missing Wall Street expectations. That came on the tail of a quarter in which Apple announced it would no longer be reporting sales figures.

Tim Cook has placed much of the iPhone’s slide at the feet of a disappointing Chinese market. It’s been a tough nut for the company to crack, in part due to a slowing national economy. But there’s more to it than that. Trade tensions and increasing tariffs have certainly played a role — and things look like they’ll be getting worse before they get better on that front, with a recent bump from a 10 to 25% tariff bump on $60 billion in U.S. goods.

It’s important to keep in mind here that many handsets, regardless of country of origin, contain both Chinese and American components. On the U.S. side of the equation, that includes nearly ubiquitous elements like Qualcomm processors and a Google-designed operating system. But the causes of a stagnating (and now declining) smartphone market date back well before the current administration began sowing the seeds of a trade war with China.

Image via Miguel Candela/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

The underlying factors are many. For one thing, smartphones simply may be too good. It’s an odd notion, but an intense battle between premium phone manufacturers may have resulted in handsets that are simply too good to warrant the long-standing two-year upgrade cycle. NPD Executive Director Brad Akyuz tells TechCrunch that the average smartphone flagship user tends to hold onto their phones for around 30 months — or exactly two-and-a-half years.

That’s a pretty dramatic change from the days when smartphone purchases were driven almost exclusively by contracts. Smartphone upgrades here in the States were driven by the standard 24-month contract cycle. When one lapsed, it seemed all but a given that the customer would purchase the latest version of the heavily subsidized contract.

But as smartphone build quality has increased, so too have prices, as manufacturers have raised margins in order to offset declining sales volume. “All of a sudden, these devices became more expensive, and you can see that average selling price trend going through the roof,” says Akyuz. “It’s been crazy, especially on the high end.”

In the last couple of years, ultra-premium flagships have broken the $1,000 barrier. As CCS Chief Research Analyst Ben Wood recently told CNET, “[Apple] did the whole industry a favor. That gave all the other manufacturers some breathing space and I can imagine there was a certain delight in the corridors of Samsung and Huawei and others.”

When it was announced in fall 2017, the iPhone X’s $999 starting price was a tough pill to swallow. In the intervening year and a half, however, there’s been a dramatic shift. Samsung followed suit, with the S10 matching that thousand-dollar price point. It’s become a kind of vicious circle — prolonged upgrade cycles have helped manufacturers justify raising prices, while four-digit flagship costs have offered an even more compelling reason for consumers to hang onto their phones for longer.

The bright spot in all of this comes from an unexpected place. In January, Huawei CEO Richard Yu made a bold prediction. “Even without the U.S. market we will be number one in the world,” he told the press. “I believe at the earliest this year, and next year at the latest.”

In most cases, such a statement would feel like executive posturing. CEOs love nothing more than cheerleading. But in the month or so between CES and MWC, it felt like a very real possibility. The last couple of years have been a bullet train of success for the Chinese smartphone and networking giant.

Even in the face of growing concerns over government ties and Iranian sanction violations that landed CFO Meng Wanzhou in Canadian detention, the company has managed to buck global smartphone trends. The company has managed to blow past Apple, becoming the world’s second largest smartphone seller. By IDC’s count, it secured that spot last summer, with 15.8% of global smartphone shipments, between Samsung’s 20.9% and Apple’s 12.1%.

Image via Andrea Verdelli/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Huawei has been a rare bright spot in what has been an absolutely dismal year for the smartphone market. The company’s meteoric rise may well be the result of a honeymoon period, with its truly premium devices having really started to arrive in earnest over the past couple of years.

“The devices that they were building two, three years ago were not as competitive as what they’re building today,” Akyuz explains “If you look at their latest lineup for the last year and a half, I believe they’ve been building some very, very good hardware. Those users who have been buying the latest P Series and the Mate Series, have had [the phones] for less than two years. We might see Huawei running into the very same problem that Apple and Samsung are suffering today.”

While Huawei’s coming of age has put it right in the sweet spot for global growth, a closer examination of the top of the market points to another key element. It’s not that Huawei has helped grow the market, so much as its push into admittedly innovative premium devices has eaten away at the market share of the competition.

Market share has remained relatively stable among top manufacturers, even as many of the also-rans have begun to fall away. Things have consolidated on the high end — as Canalys notes above, market share among the top five smartphone vendors rose from 66.8 to 72% of the total global market — a trend that’s likely to continue as smaller manufacturers struggle to grapple with larger market trends.

“They haven’t grown the pie,” Gartner analyst Tuong Nguyen tells TechCrunch.” They’ve taken pieces of other vendors’ pies by pushing their marketing strategy (to drive their brand perception). “They were also smart about doing this as a dual-brand strategy — to both the high end as well as the mid/low tier. This gives them access to a broader segment of the market than if they were to just focus on the high end and it gives them the aspirational products that mid/low tier users can aspire to own and associate with.”

Huawei’s success with diversification appears to have had a marked influence on the competition. In the past year, Apple, Samsung and Google have all introduced low-cost versions of their flagships. Ahead of the recent launch of the Pixel 3a, Google was very upfront about the strategy.

CEO Sundar Pichai wouldn’t disclose specific Pixel 3 sales figures, but did cite “year over year headwinds” while discussing the device’s struggles.

Ahead of the 3a’s announcement, Google VP of Product Management Mario Queiroz spelled out the strategy for me. “The smartphone market has started to flatten. We think one of the reasons is because, you know, the premium segment of the market is a very large segment, but premium phones have gotten more and more expensive, you know, three, four years ago, you could buy a premium phone for $500.”

The addition of budget flagships like the iPhone XR, Samsung S10e and Pixel 3a aren’t going to turn around the smartphone market, but they will go a ways toward helping companies diversify their offerings. It’s all part of making smartphone sales less beholden to those who are willing to shell out $1,000 every two years for a handset.

Lower-cost devices also open companies to additional emerging markets. There’s a kind of unavoidable saturation point among established markets. With a massive population and a booming economy, China made sense as a place for companies like Apple to grow the market. With the country suffering similar slowdowns as the rest of the world, however, other locations have emerged, including, most notably, India.

New numbers from IDC note that the world’s second most populous country has managed to buck recent global trends. India’s smartphone shipments grew 7% year over year for Q1, even as the global market shrunk 6%. That’s been particularly good news for Chinese manufacturers like Xiaomi, Vivo and Oppo.

Samsung and OnePlus have also found success in the market with their relatively premium offerings ($500+). After stumbling in China, Apple clearly sees tremendous opportunity in the Indian market as well. The company continues to manufacture the iPhone 6s in the country for the local market, keeping the prime of headphone jack alive for a little longer, at least.

Canalys Research Analyst Vincent Thielke tells TechCrunch that Huawei also has tremendous potential to grow in locales where it’s not currently banned. “In markets outside of North America, there is still room for Huawei to keep growing at the expense of other players,” he says. “Overseas, we have noted strong growth by Huawei in all markets outside of North America, including an explosion in Latin America and Central and Eastern Europe, geographies where Huawei’s value for money proposition resonates more with consumers. In these markets, there is an opportunity for Huawei to attract new users and convert them from the likes of Samsung.”

While these emerging markets have tremendous potential, continued success is going to require that manufacturers find a way to sustain growth in existing markets. What’s clear is that manufacturers’ yearly upgrade cycle is doing less to move the needle than it was a year or two back. As companies like Google and Apple increasingly rely on advances in software, AI and ML to improve things like imaging, it’s going to be increasingly difficult to distinguish phones based on hardware innovations.

Two recent innovations have the potential to buck that trend, however. 5G and foldable caused quite the stir at Mobile World Congress a few months back. Understandably so. These two pieces have the potential to kickstart stagnant smartphone sales figures, but there are still a number of issues to surmount. For starters, there’s the issue of price. Take the Samsung S10 5G that launched on Verizon earlier this week. The handset starts at $1,300 — but that pales in comparison to the Fold, which will run $1,980 if and when it finally does launch. Huawei’s foldable Mate X, which packs in 5G by default, is even pricier, starting at $2,600. Twice the phone at twice the price, as it were.

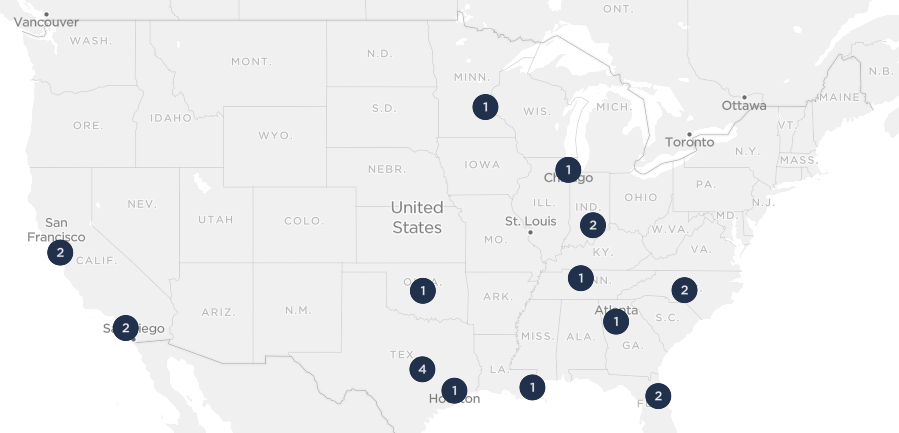

There’s a big issue of the order of the cart and the horse here, of course. Early adopters might shell out that money after companies have teased these technologies for years now. But 5G is rolling out with a trickle in 2019. Here in the States, Verizon’s 5G is available in parts of Chicago and Minneapolis, with additional areas rolling out later in the year. Sprint promises to cover parts of nine markets “in the coming weeks.”

And then there’s AT&T, which has happily muddied the waters with its extremely misleading “5GE” labeling. The carrier has promised nation-wide (real) 5G in 2020. That, fittingly, is also when Apple is expecting to launch a 5G iPhone.

Here’s a breakdown of what things look like right now:

[Source: Speedtest]

I don’t see an issue with manufacturers launching 5G devices at this early stage, so long as both they and the carriers are realistic about what people will be getting for their money. 5G is essentially an inevitability, but it’s far from a mainstream product, meaning it likely won’t start truly driving upgrades until next year at the earliest.

Akyuz concurs, explaining that he expects 5G to become a major sales catalyst in the second half of next year, adding that the technology is still lacking the killer app to make devices compelling at their current price point. Foldables will likely get a slow start, as well.

Way back in 2016, one analyst predicted that foldables would make up about a fifth of the market in 2019. That’s obviously been scaled back a lot. Samsung’s Galaxy Fold, the first truly commercial foldable, simply wasn’t ready for prime time. Chances are the device will launch over the summer, but early units’ tendency to break in reviewers hands have significantly dampened the desire for what was already shaping up to be a niche device.

Anyone who monitors this stuff with even the slightest hint of pragmatism will tell you there’s no magic bullet for an ailing smartphone market. There is hope, however. Canalys notes that Samsung’s latest flagship hit solid sales numbers, proving that a solid device with nice new features can still convince cautious consumers to upgrade.

“There is a role for new hardware innovations in reviving downward sales, and this is especially true in North America,” says Thielke. “We saw the S10’s hardware innovations help drive regional growth for Samsung, and we expect Apple will see a relative improvement in North America next year with its September hardware refresh.”

With those notes of hope just over the horizon, however, it seems that the smartphone’s honeymoon is over.