An analysis of political advertisers running extensive campaigns on Facebook targeting users in the United States over the past six months has flagged a raft of fresh concerns about its efforts to tackle election interference — suggesting the social network’s self regulation is offering little more than a sham veneer of accountability.

Dig down and all sorts of problems and concerns become apparent, according to new research conducted by Jonathan Albright, of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism.

Where’s the recursive accountability?

Albright timed the research project to cover the lead up to the US midterms, which represent the next major domestic test of Facebook’s democracy-denting platform — though this time it appears that homegrown disinformation is as much, if not more, in the frame than Kremlin-funded election fiddling.

The three-month project to delve into domestic US political muck spreading involved taking a thousand screen shots and collecting more than 250,000 posts, 5,000 political ads, and the historic engagement metrics for hundreds of Facebook pages and groups — using “a diverse set of tools and data resources”.

In the first of three Medium posts detailing his conclusions, Albright argues that far from Facebook getting a handle on its political disinformation problem the dangers appear to have “grown exponentially”.

The sheer scale of the problem is one major takeaway, with Albright breaking out his findings into three separate Medium posts on account of how extensive the project was, with each post focusing on a different set of challenges and concerns.

In the first post he zooms in on what he calls “Recursive Ad-ccountability” — or rather Facebook’s lack of it — looking at influential and verified Pages that have been running US political ad campaigns over the past six months, yet which he found being managed by accounts based outside the US.

Albright says he found “an alarming number” of these, noting how Page admins could apparently fluctuate widely and do so overnight — raising questions about how or even whether Facebook is even tracking Page administrator shifts at this level so it can factor pertinent changes into its political ad verification process.

Albright asserts that his findings highlight both structural loopholes in Facebook’s political ad disclosure system — which for example only require that one administrator for each Page get “verified” in order to be approved to run campaigns — but also “emphasize the fact that Facebook does not appear to have a rigid protocol in place to regularly monitor Pages running political campaigns after the initial verification takes place”.

So, essentially, it looks like Facebook doesn’t make regular checks on Pages after an initial (and also flawed) verification check — even, seemingly, when Pages’ administrative structure changes almost entirely. As Albright puts it, the company lacks “recursive accountability”.

Responding to Albright’s research, Facebook has emphasized that its Authorization system is “tied to the person not the Page”, noting that only the location-verified Admin can place a political ad. “Other admins will not be able to run ads related to politics if they are based outside the US. We’re also exploring ways for continued eligibility to run ads related to politics or issues,” it told us.

However Albright says his point was about Page management — and the fact non-US based individuals still have access to campaign responses and Page insights. A point Facebook has not addressed.

Other issues of concern he flags include finding ad campaigns that had foreign Page managers using “information-seeking “polls” — aka sponsored posts asking their target audiences, in this case American Facebook users, to respond to questions about their ideologies and moral outlooks”.

Which sounds like a rather similar modus operandi to disgraced (and now defunct) data company Cambridge Analytica’s use of a quiz app running on Facebook’s platform to extract personal data and psychological insights on users (which it repurposed for its own political ad targeting purposes).

Albright also unearthed instances of influential Pages with foreign manager accounts that had run targeted political campaigns for durations of up to four months without any “paid for” label — a situation that, judging Facebook’s system by face value, shouldn’t even be possible. Yet there it was.

On this, Facebook said: “As part of our commitment to transparency, we include ads that ran without a “Paid for by” disclaimer on Facebook and should have in our Ad Archive up to seven years. We’ve always said enforcement isn’t perfect, which is why we welcome people reporting an ad they think requires authorization and a “Paid for by” disclaimer. The advertiser can appeal if they believe their ad isn’t related to politics or issues of national importance.”

There are of course wider issues with ‘paid for’ labels, given they aren’t linked to accounts — making the entire system open to abuse and astroturfing, which Albright also notes.

“After finding these huge discrepancies, I found it difficult to trust any of Facebook’s reporting tools or historical Page information. Based on the sweeping changes observed in less than a month for two of the Pages, I knew that the information reported in the follow-ups was likely to be inaccurate,” he writes damningly in conclusion.

“In other words, Facebook’s political ad transparency tools — and I mean all of them — offer no real basis for evaluation. There is also no ability to know the functions and differential privileges of these Page “managers,” or see the dates managers are added or removed from the Pages.”

Asked whether it intends to expand its ad transparency tools to include more information about Page admins, Facebook told us:

We’re focused on helping to prevent foreign interference in elections and that starts with requiring people placing ads related to politics or issues to confirm their identity and location, as well as accurately disclose who paid for the ad. We’re also housing all these ads in an Ad Archive for up to seven years and providing information on who saw the ad, like their gender, age or location… We launched an “Info and Ads” section which shows you all the ads a Page is currently running as well as more info about the Page like when it was created. We’re going to continue to work on this and get better over time.

The company has made a big show of launching a disclosure system for political advertisers, seeking to run ahead of regulators. Yet its ‘paid for’ badge disclosure system for political ads has quickly been shown as trivially easy for astroturfers to bypass, for example…

The company has also made a big domestic PR push to seed the idea that it’s proactively fighting election disinformation ahead of the midterms — taking journalists on a tour of its US ‘election security war room‘, for example — even as political disinformation and junk news targeted at American voters continues being fenced on its platform…

The disconnect is clear.

Shadow organizing

In a second Medium post, dealing with a separate set of challenges but stemming from the same body of research, Albright suggests Facebook Groups are now playing a major role in the co-ordination of junk news political influence campaigns — with domestic online muck spreaders seemingly shifting their tactics.

He found bad actors moving from using public Facebook Pages (presumably as Facebook has responded to pressure and complaints over visible junk) to quasi-private Groups as a less visible conduit for seeding and fencing “hate content, outrageous news clips, and fear-mongering political memes”.

“It is Facebook’s Groups— right here, right now — that I feel represents the greatest short-term threat to election news and information integrity,” writes Albright. “It seems to me that Groups are the new problem — enabling a new form of shadow organizing that facilitates the spread of hate content, outrageous news clips, and fear-mongering political memes. Once posts leave these Groups, they are easily encountered, and — dare I say it —algorithmically promoted by users’ “friends” who are often shared group members — resulting in the content surfacing in their own news feeds faster than ever before. Unlike Instagram and Twitter, this type of fringe, if not obscene sensationalist political commentary and conspiracy theory seeding is much less discoverable.”

Albright flags how notorious conspiracy outlet Infowars remains on Facebook’s platform in a closed Group form, for instance. Even though Infowars has previously had some of its public videos taken down by Facebook for “glorifying violence, which violates our graphic violence policy, and using dehumanizing language to describe people who are transgender, Muslims and immigrants, which violates our hate speech policies”.

Facebook’s approach to content moderation typically involves only post-publication content moderation, on a case-by-case basis — and only when content has been flagged for review.

Within closed Facebook Groups with a self-selecting audience there’s arguably likely to be less chance of that.

“This means that in 2018, the sources of misinformation and origins of conspiracy seeding efforts on Facebook are becoming invisible to the public — meaning anyone working outside of Facebook,” warns Albright. “Yet, the American public is still left to reel in the consequences of the platform’s uses and is tasked with dealing with its effects. The actors behind these groups whose inconspicuous astroturfing operations play a part in seeding discord and sowing chaos in American electoral processes surely are aware of this fact.”

Some of the closed Groups he found seeding political conspiracies he argues are likely to break Facebook’s own content standards did not have any admins or moderators at all — something that is allowed by Facebook’s terms.

“They are an increasingly popular way to push conspiracies and disinformation. And unmoderated groups — often with of tens of thousands of users interacting, sharing, and posting with one other without a single active administrator are allowed [by Facebook],” he writes.

“As you might expect, the posts and conversations in these Facebook Groups appear to be even more polarized and extreme than what you’d typically find out on the “open” platform. And a fair portion of the activities appear to be organized. After going through several hundred Facebook Groups that have been successful in seeding rumors and in pushing hyper-partisan messages and political hate memes, I repeatedly encountered examples of extreme content and hate speech that easily violates Facebook’s terms of service and community standards.”

Albright couches this move by political disinformation agents from seeding content via public Pages to closed Groups as “shadow organizing”. And he argues that Groups pose a greater threat to the integrity of election discourse than other social platforms like Twitter, Reddit, WhatsApp, and Instagram — because they “have all of the advantages of selective access to the world’s largest online public forum”, and are functioning as an “anti-transparency feature”.

He notes, for example, that he had to use “a large stack of different tools and data-sifting techniques” to locate the earliest posts about the Soros caravan rumor on Facebook. (And “only after going through thousands of posts across dozens of Facebook Groups”; and only then finding “some” not all the early seeders.)

He also points to another win-win for bad actors using Groups as their distribution pipe of choice, pointing out they get to “reap all of the benefits of Facebook— including its free unlimited photo and meme image hosting, its Group-based content and file sharing, its audio, text, and video “Messenger” service, mobile phone and app notifications, and all the other powerful free organizing and content promoting tools, with few — if any — of the consequences that might come from doing this on a regular Page, or by sharing things out in the open”.

“It’s obvious to me there has been a large-scale effort to push messages out from these Facebook groups into the rest of the platform,” he continues. “I’ve seen an alarming number of influential Groups, most of which list their membership number in the tens of thousands of users, that seek to pollute information flows using suspiciously inauthentic but clearly human operated accounts. They don’t spam messages like what you’d see with “bots”; instead they engage in stealth tactics such as “reply” to other group members profiles with “information.”

“While automation surely plays a role in the amplification of ideas and shared content on Facebook, the manipulation that’s happening right now isn’t because of “bots.” It’s because of humans who know exactly how to game Facebook’s platform,” he concludes the second part of his analysis.

“And this time around, we saw it coming, so we can’t just shift the blame over to foreign interference. After the midterm elections, we need to look closely, and press for more transparency and accountability for what’s been happening due to the move by bad actors into Facebook Groups.”

The shift of political muck spreading from Pages to Groups means disinformation tracker tools that only scrape public Facebook content — such as the Oxford Internet Institute’s newly launched junk news aggregator — aren’t going to show a full picture. They can only given a snapshot of what’s being said on Facebook’s public layer.

And of course Facebook’s platform allows for links to closed Group content to posted elsewhere, such as in replies to comments, to lure in other Facebook users.

And, indeed, Albright says he saw bad actors engaging in what he dubs “stealth tactics” to quietly seed and distribute their bogus material.

“It’s an ingenious scheme: a political marketing campaign for getting the ideas you want out there at exactly the right time,” he adds. “You don’t need to go digging in Reddit, or 4 or 8 Chan, or crypochat for these things anymore. You’ll see them everywhere in political Facebook Groups.”

The third piece of analysis based on the research — looking at Facebook’s challenges in enforcing its rules and terms of service — is slated to follow shortly.

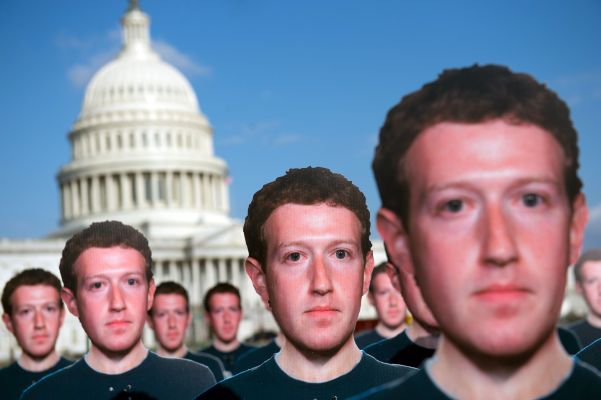

Meanwhile this is the year Facebook’s founder, Mark Zuckerberg, made it his personal challenge to ‘fix the platform’.

Yet at this point, bogged down by a string of data scandals, security breaches and content crises, the company’s business essentially needs to code its own apology algorithm — given the volume of ‘sorries’ it’s now having to routinely dispense.

Late last week the Intercept reported that Facebook had allowed advertisers to target conspiracy theorists interested in “white genocide”, for example — triggering yet another Facebook apology.

Facebook also deleted the offending category. Yet it did much the same a year ago when a ProPublica investigation showed Facebook’s ad tools could be used to target people interested in “How to burn Jews”.

Plus ça change then. Even though the company said it would hire actual humans to moderate its AI-generated ad targeting categories. So it must have been an actual human who approved the ‘white genocide’ bullseye. Clearly, overworked, undertrained human moderators aren’t going to stop Facebook making more horribly damaging mistakes.

Not while its platform continues to offer essentially infinite ad-targeting possibilities — via the use of proxies and/or custom lookalike audiences — which the company makes available to almost anyone with a few dollars to put towards whipping up hate and social division, around their neo-fascist cause of choice, making Facebook’s business richer in the process.

The social network itself — its staggering size and reach — increasingly looks like the problem.

And fixing that will require a lot more than self-regulation.

Not that Facebook is the only social network being hijacked for malicious political purposes, of course. Twitter has a long running problem with nazis appropriating its tools to spread hateful content.

And only last month, in a lengthy Twitter thread, Albright raised concerns over anti-semitic content appearing on (Facebook-owned) Instagram…

But Facebook remains the dominant social platform with the largest reach. And now its platform seems appears to be offering election fiddlers the perfect blend of mainstream reach plus unmoderated opportunity to skew political outcomes.

“It’s like the worst-case scenario from a hybrid of 2016-era Facebook and an unmoderated Reddit,” as Albright puts it.

The fact that other mainstream social media platforms are also embroiled in the disinformation mess doesn’t let Facebook off the hook. It just adds further fuel to calls for proper sector-wide regulation.

This post was updated with comment from Facebook and additional comment from Albright