Apple today announced it’s amending the App Store guideline that banned apps created using templates and other app generation services. When the company revised its policies earlier this year, the move was meant to reduce the number of low-quality apps and spam. But the decision ended up impacting a much wider market — including small businesses, restaurants, nonprofits, organizations, clubs and others who don’t have the in-house expertise or funds to build custom apps from scratch.

Apple’s new rule is meant to offer better clarity on what sort of apps will and will not be accepted in the App Store.

Before, the 4.2.6 App Store guideline read as follows:

4.2.6 Apps created from a commercialized template or app generation service will be rejected.

The company’s revised wording now states:

4.2.6 Apps created from a commercialized template or app generation service will be rejected unless they are submitted directly by the provider of the app’s content. These services should not submit apps on behalf of their clients and should offer tools that let their clients create customized, innovative apps that provide unique customer experiences.

Another acceptable option for template providers is to create a single binary to host all client content in an aggregated or “picker” model, for example as a restaurant finder app with separate customized entries or pages for each client restaurant, or as an event app with separate entries for each client event.

This is Apple’s attempt to clarify how it thinks about templated apps.

Core to this is the idea that, while it’s fine for small businesses and organizations to go through a middleman like the app templating services, the app template providers shouldn’t be the ones ultimately publishing these apps on their clients’ behalf.

Instead, Apple wants every app on the App Store to be published by the business or organization behind the app. (This is something that’s been suggested before). That means your local pizza shop, your church, your gym, etc. needs to have reviewed the App Store documentation and licensing agreement themselves, and more actively participate in the app publishing process.

Apple in early 2018 will waive the $99 developer fee for all government and nonprofits starting in the U.S. to make this transition easier.

It’s still fine if a middleman — like a template building service — aids them in this. And it’s also fine if a template-building service helps them create the app in the first place. In fact, Apple isn’t really concerned so much about “how” the app gets built (so long as it’s not a wrapped webpage) — it cares about the end result.

Apps need to offer high-quality experience, the company insists. They shouldn’t all look identical; they shouldn’t look like clones of one another. And, most importantly, they shouldn’t look like the web or serve as just a wrapper around what could otherwise just be the business website or their Facebook Page.

Apps are meant to be more than the web, offering a deeper, richer experience, Apple believes.

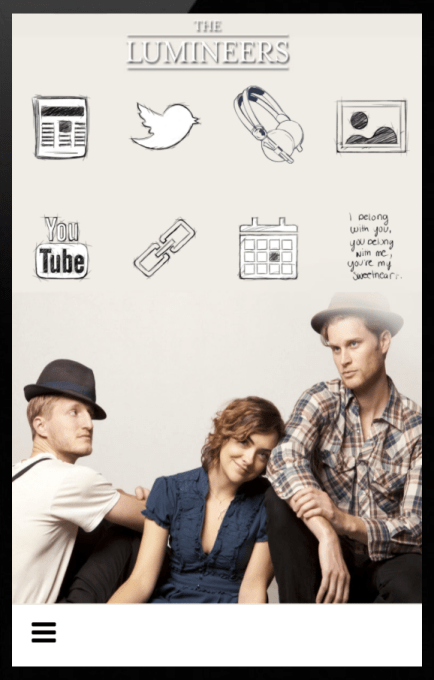

Above: The original version of the Official Lumineers app, built by AppMakr

There is some disagreement on how extensively this rule is being enforced, however.

Today, consumers may interact with one of these “templated clones” — like an app for their favorite taco place, their church, a local band, their school, etc. They don’t know that the app is one of many that look just like it, and they probably don’t care.

In addition, a sort of uniformity to apps in a given space could make them easier to use, some argue. You’ll know where to find the “mobile ordering” feature, or where the menu is located when they’re not all unique snowflakes, trying to be different for difference’s sake.

On the flip side, Apple sees an ecosystem filled with thousands of copycats and clones as a very bad thing. It’s unfair to developers who have custom-built their apps, and it can even crash the App Store when one tries to load some 20,000 apps published under a single developer account.

While most generally agree that low-quality apps don’t deserve to be on the App Store, there’s industry concern that banning template-based apps as a whole has been an overreach.

The move even caught the attention of Congressman Ted W. Lieu (33rd District, California), who told Apple it was “casting too wide a net” in its effort to remove spam and illegitimate apps from the App Store, and was “invalidating apps from longstanding and legitimate developers who pose no threat to the App Store’s integrity.”

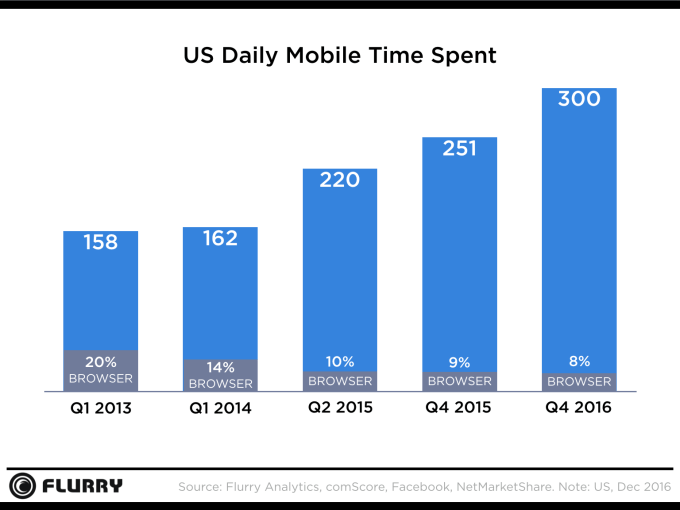

It seemed odd, too, that a company that on the one hand had argued that everyone deserved free and equal access to the internet created a rule that makes it more difficult for smaller companies and nonprofits from doing business on the App Store — especially at a time when accessing the web is more often done through the gateway of mobile apps. (See above chart — the browser is passé).

At the very least, this amended language seems to offer some respite for the templating service providers. They can still act as a middleman for the smaller companies, so long as they build customized apps that don’t look like one another, and the clients publish them under their own accounts. They can even use components to build those apps, as long as the apps have variety to their interfaces and offer an app-like, not web-like, experience.

The rule arguably is meant to offer consumers a better App Store filled with well-built, quality apps, but it will have a sweeping effect on small businesses and their ability to compete with larger entities. Sure, the pizza place could sell through Uber Eats — but at a steep cost. Sure, the nail salon could advertise on Yelp or the mom-and-pop could have a Facebook Page — and many do, of course. Such is the nature of the world. But that also puts the business at the mercy of the larger aggregators, while an app — much like a website — puts the business in more control over their own destiny.

Recently, TechCrunch reported that many companies operating in this space were given a January 1, 2018 deadline for compliance with the revised guidelines. After this date, the App Store Review team told the companies their new apps wouldn’t be allowed in the App Store. Some apps had already fallen under the ban, and were seeing their submissions rejected. (Apps already live were grandfathered in, and could be updated. But it was unclear how long that would be the case.)

Some companies had even shut down their business as a result of these changes.

The adjusted language doesn’t appear to allow them to continue as they did before. Instead, they will need to develop new tools to provide clients with “customized, innovative apps that provide unique customer experiences.”

In other words, be more like Squarespace, less like Google Sites — but for apps.

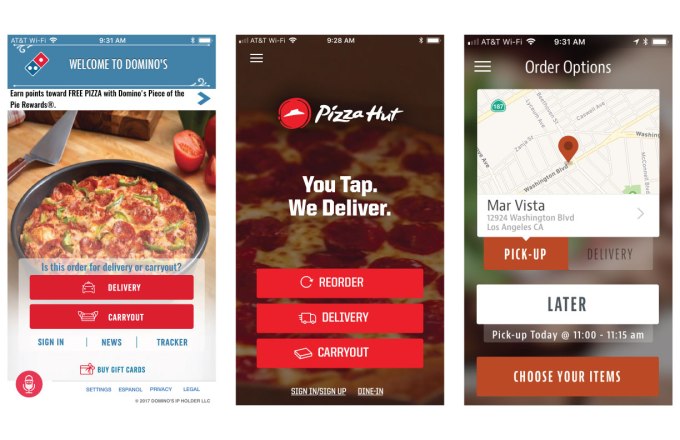

Above: One of these is a template-based app. You can tell, right?

The affected companies weren’t all what you considered “spam” app makers. While of course some that were wrapping webpages made sense to ban, others operated in more of a gray area.

They ranged from those that offered tools for small businesses that wanted their own app store presence to those that served particular industries — like ChowNow, which builds apps for restaurants that want their own mobile ordering systems, or those that build apps for churches, fitness studios, spas, politicians, events and more.

These businesses told us the 4.2.6 (and sometimes the 4.3) guidelines were being cited by the App Review team when rejecting their apps. They also told us they had trouble getting clarity from Apple when discussing the matter in private, one-on-one phone calls.

The former rule (4.2.6) bans the template-based apps, while the latter (4.3) is more of a catch-all for banning spam. The 4.3 rule was used at times when Apple couldn’t prove that the app was built using a wizard or drag-and-drop system, we were told.

[gallery ids="1580398,1580397"]

Above: the wording of the rules before today’s changes

When Apple first announced the changes at WWDC, many of these template providers and app generation services thought they wouldn’t be impacted — the ban was meant to weed out the clone-makers and spammers. That’s why it came as a surprise when Apple reviewers began informing them that they, too, would no longer be allowed to publish their apps to the App Store. They didn’t think of themselves as spammers.

Apple’s newly worded policy provides more clarity on the matter, but it doesn’t really change Apple’s prior intention.

If the app is basically just a website, if it looks like other apps, then don’t bother; the App Store is not for you.