Since Isaac Asimov first laid out the three laws of robotics in 1942, human safety has been the No. 1 concern of the inventors, innovators and futurists who have pondered our place in the age of robots.

But for robots to be able to ensure human safety, those robots must be able to see humans and recognize them as humans. That’s where Veo Robotics comes in.

The Cambridge, Mass.-based company sees itself as building the brains for robotic systems — the ability for these robots to be aware of their surroundings.

It’s also something that Veo’s founding team — chief executive Patrick Sobalvarro; Clara Vu, the company’s vice president of engineering; and Scott Denenberg, Veo’s senior director of hardware — have spent a combined 50 years addressing through work in robotics, artificial intelligence, sensor perception and industrial automation.

For Sobalvarro, the former president of Rethink Robotics, the eureka moment was discovering that what his previous company’s industrial customers really wanted weren’t small robots that worked the assembly line, but a way for the massive, giant, deadly industrial robots already installed in factories to be able to work with humans more effectively.

“We can override the controls on that robot and allow it to behave in a responsive way to the presence of a human,” says Sobalvarro. “That’s different from what happened in the previous generation of collaborative robotics.”

Sobalvarro compares the multi-million dollar robots currently whirring away on factory floors around the globe to the plow horses agrarian farmers used to furrow their fields in those halcyon days before the industrial revolution.

“In the same way that a farmer might use a plow horse and be confident that the horse will not step on the farmer, we make robots see where people are and then respond to their presence,” he told me.

The problem for manufacturers isn’t that they can’t already replace human workers with machines, the problem is that if they do that, they’ll get pretty crappy products.

Bryce Durbin

“If you do use complete automation and no people in a factory, you end up with an inefficient system and quality problems,” Sobalvarro says. “We want to give you big robots that are very precise and very strong without taking away the intelligence that people bring to manufacturing.”

Big manufacturers think about this frequently, and it was one of the reasons why Veo was able to snag its initial seed funding from Next47, the investment arm for the German industrial manufacturing giant, Siemens, says Sobalvarro.

There’s no denying that manufacturing is on the cusp of a robot revolution. China alone plans to be able to manufacture 100,000 robots annually by 2020. The country already occupies the pole position in the robotics race. It’s home to more industrial robots than any other country and is continuing to lap what’s a $30 billion market (ahead of South Korea, Japan and the U.S.).

China is also a market where Veo has yet to plant a flag, according to Sobalvarro. “We spend a fair bit of time in Europe, and, of course, in the U.S. We work with Japanese manufacturers in the U.S. as well… we do not, so far, have any partnerships in China,” he said.

At Veo, China’s rise is an issue for another day. Right now, the company is focused on getting its robot “brains” into machines in the near term.

That’s the reason why it brought on the additional financing from Lux Capital and GV to fuel further research and development and the eventual product roll out.

Veo’s founders and its investors believe that a focus on robot awareness and human safety can actually move to assuage fears that robots will replace humans.

“For decades we’ve been told robots were to blame for the dearth of manufacturing jobs in the U.S., but that’s about to change,” said Bilal Zuberi, partner at Lux Capital, and a new director on the company’s board, in a statement. “If you improve the robots, manufacturers will be able to hire more people for better jobs. Veo is giving industrial robots the gift of perception and intelligence so these helpful machines can still do the dangerous heavy lifting, yet safely work alongside humans.”

As for how Veo works, here’s a description of the technology from our previous coverage:

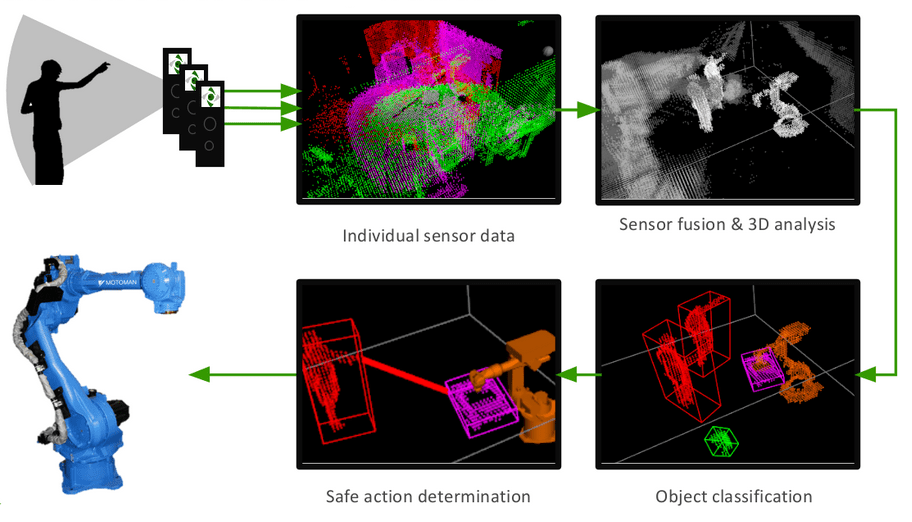

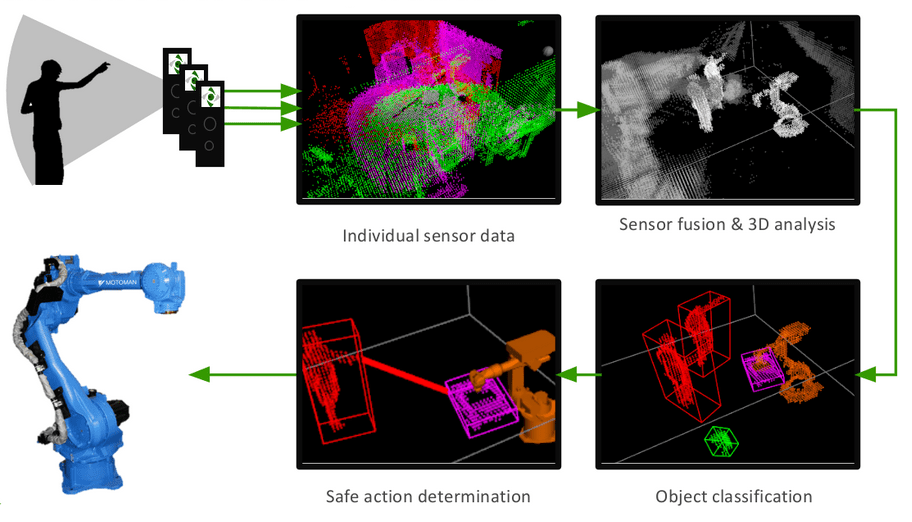

Veo’s system uses a set of four depth-sensing cameras placed around the work space so as to give complete visual coverage. Once you’ve established that, you designate various things as work pieces, forbidden areas and so on.

This logic sits lightly on top of the robot’s ordinary controller; you don’t have to redo everything or add the exact dimensions of girders to be carried and safe places for humans to stand. The robot operates as it would otherwise, except now it knows the exact location and size of everything in its field of view. If a human or vehicle intrudes, or a piece breaks, or there’s some other deviation from the norm, it can slow or stop.

This logic sits lightly on top of the robot’s ordinary controller; you don’t have to redo everything or add the exact dimensions of girders to be carried and safe places for humans to stand. The robot operates as it would otherwise, except now it knows the exact location and size of everything in its field of view. If a human or vehicle intrudes, or a piece breaks, or there’s some other deviation from the norm, it can slow or stop.

Critically, if the system is ever not 100 percent sure that it’s safe — for instance, if a camera is obscured or it can’t see behind a large piece — the robot comes to a full stop.

“There is a significant market opportunity for intelligent software that enables safe interaction between humans and machines in industrial environments,” said Andy Wheeler, general partner at GV, in a statement.

For Sobalvarro there are three trends that continue to drive human relevance in the factory: customization, customer choice and customer expectations.

He said that the mass customization available to consumers means that factories need to be more flexible — and flexible in a way that can’t really be automated to the degree that people think. It’s humans that are swapping out the fine features on an assembly line after the framework of a product is assembled by a machine, he said.

Beyond customization, the increasing number of products available to consumers also requires more flexibility in factories, which, again, means more human employees to do certain jobs. And finally, the speed at which consumption cycles have increased means that factories need to be flexible not just at the product level, but at a product line level — with assembly lines able to swap out one product line for another.

“You put those three things together and what that means is that you’re changing your assembly line all the time,” Sobalvarro said.

He points to the recent problems at Tesla with the rollout of the Tesla 3 as an example of the challenges that manufacturers face.

“The Tesla 3 was being made with a lot of human labor. And it’s not surprising to me that a brand new product would require a lot of that… the most flexible and intelligent resource you have in a manufacturing plant are the human worker. They’re not going to be subbed out til true AI is getting solved.”

While Veo may save people’s factory jobs, the technology isn’t ready for prime time just yet. “You have to run a documented process and you have to be certified,” Sobalvarr0 says of the hurdles it takes to get a service like his onto the factory floor.

The company is working with the certification body, TUV, and expanding its work with the testing company. It will be rolling out in three or four pilot locations in the next six months for additional testing at an auto manufacturer, a consumer packaged goods company, a distribution and logistics company and a household products manufacturing company.

As for the robot takeover, Sobalvarro says don’t buy it.

“That worker on the line is actually key,” he said. “Their intelligence and their creativity is actually key to creating any new product. We see the presence of human workers becoming more valuable and that’s what we hear from manufacturers.”