He might not want to run for office any time soon, but Mark Zuckerberg has perfected the time-honored political art of talking a lot without saying anything.

In a sprawling letter consisting mostly of feel-good mumbo jumbo and a light sprinkling of feature ideas, the Facebook visionary laid out 5,700 words’ worth of nonspecific stuff that sounds nice. Like fellow Facebook feel-gooder Sheryl Sandberg, Zuck was sure to drive home the warm/fuzzy message of his ad-dollar factory, hitting isolated human interest anecdotes with more frequency than the evening news.

While his desire for corporate self-reflection is mildly admirable in an industry loath to introspect, all of those words don’t manage to add up to the sum of their parts. (Seriously, that’s kind of a lot of words.) Of course, Zuck is right that Facebook does have a uniquely huge opportunity to do novel things at massive scale. But what can you really pull off if your number one goal is to avoid rocking a boat full of nearly two billion people?

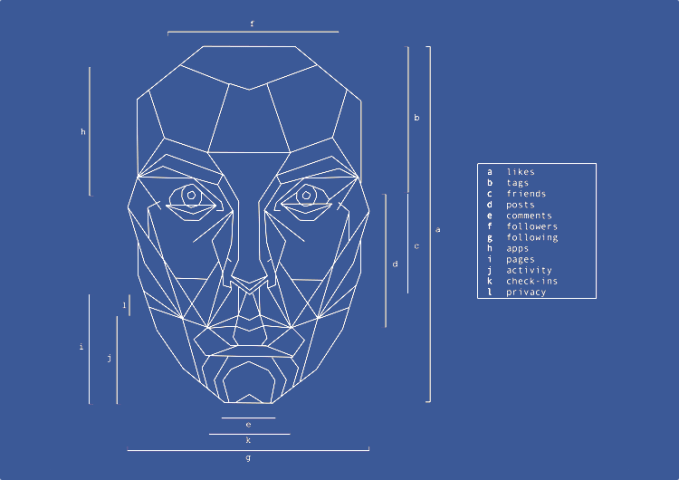

For a snapshot of what the letter discussed, we broke down a few topics by number of mentions:

- Social infrastructure: 15

- Global: 26

- Politics/Political: 10

- Trump: 0

- Harassment: 1

- Fake news: 1

- Hoax: 3

- Propaganda: 1

- Instagram: 0

- WhatsApp: 3

- Encryption: 2

Zuck’s greater good

- First off, the word “Trump” appears zero times. Zuckerberg’s apolitical treatise predictably makes no mention of the U.S. president, opting instead for palatable allusions to a climate of polarized viewpoints and the looming threat and/or promise of globalization. In lieu of enumerating specific policies, Zuck goes big here. Unfortunately, it’s more “undergrad sociology term paper big” than “compelling big ideas big.”

- In the letter, Zuckerberg indulges in some weird exceptionalism around this moment in time, abdicating responsibility for Facebook’s role in creating the moment we’re living through. Facebook’s modus operandi has always been to take credit for anything good accomplished on its network and dismiss anything bad as an external phenomenon. This strategy proves advantageous time and time again.

- Zuck believes in something he calls “our collective values and common humanity,” which appears to be shorthand for a watered-down kind of politics that isn’t about anything at all. He opines about “the vast scale of people’s intrinsic goodness aggregated across our community” without doing much to acknowledge humanity’s aggregate badness.

- Do the good actions made possible by the platform (Red Cross donations, volunteer mobilization) cancel out the bad (harassment, neo-Nazi affinity groups)? Zuck doesn’t ask this question, nor does he answer it.

Privacy

- Facebook wants to expand the power of its predictive safety features using artificial intelligence. That could affect everything from disaster relief to suicide prevention to terrorism.

- He noted the importance of “protecting individual security and liberty” but did not immediately offer a solution to the risks inherent in this model beyond touting Facebook’s adoption of end-to-end encryption in its chat apps. Encryption will do little to curtail the privacy risk inherent in AI, facial recognition software and other kinds of algorithms that can predict user identity and behavior.

Fake news

Fake news

- Zuckerberg suggests that providing a “range of perspectives” will combat fake news and sensational content over time, but this appears to naively assume users have some inherent drive to seek the truth. Most social science suggests that people pursue information that concerns their existing biases, time and time again. Facebook does not have a solution for how to incentivize users to behave otherwise.

- Even if we’re friends with people like ourselves, Zuckerberg thinks that Facebook feeds display “more diverse content” than newspapers or broadcast news. That’s a big claim, one that seems to embrace Facebook’s identity as a media company, and it’s not backed up by anything at all.

- Facebook explains that its approach “will focus less on banning misinformation, and more on surfacing additional perspectives and information.” For fear of backlash, Facebook will sit this one out, pretty much.

- Zuckerberg thinks the real problem is polarization across not only social media but also “groups and communities, including companies, classrooms and juries,” which he clumsily dismisses as “usually unrelated to politics.” Basically, Facebook will reflect the systemic inequities found elsewhere in society and it shouldn’t really be expected to do otherwise.

- Zuck “[wants] to emphasize that the vast majority of conversations on Facebook are social, not ideological.” By design, so are the vast majority of conversations Facebook has about Facebook. The company continues to be terrified of appearing politically or ideologically aligned.

Diversity/Inclusion:

In one of the only substantive bits, Zuckerberg owns up to some of his platform’s recent shortcomings:

“In the last year, the complexity of the issues we’ve seen has outstripped our existing processes for governing the community. We saw this in errors taking down newsworthy videos related to Black Lives Matter and police violence, and in removing the historical Terror of War photo from Vietnam. We’ve seen this in misclassifying hate speech in political debates in both directions — taking down accounts and content that should be left up and leaving up content that was hateful and should be taken down. Both the number of issues and their cultural importance has increased recently.”

You had us right up until that last sentence.

Facebook’s raison d’être

Sure, it’s nice that Facebook wants to do Good Things, but it’d be nicer if the company didn’t beat us over the head with its own ostensible selflessness. It’s hard to find inspiration in Facebook’s grand global mission when the fact of the matter is that it stands to make a lot of money by expanding into countries it has yet to conquer. This remains the obvious undercurrent behind its global mission to nobly connect everyone everywhere.

This should go without saying, but a lot of users (and plenty of reporters) seem unduly charmed by Facebook’s humanitarian overtures. Facebook engages in a lot of strategic philanthropy, but that doesn’t make its mission philanthropic. Its mission is making money. It’s okay to say that!

While Zuckerberg’s letter is not particularly profound, his message is clear: Facebook, the great equivocator, is truly for everyone. The lowest common denominator of digital socialization works extraordinarily well for no one in particular. By rallying around a nebulous notion of a greater good that flows through humanity at scale (miraculously alienating no one in the process!), Facebook can be some things to all people — and that’s really been its true mission all along.

Perhaps we should all put aside our differences and join hands on the next quarterly earnings call?