Someone across the room throws you a ball and you catch it. Simple, right?

Actually, this is one of the most complex processes we’ve ever attempted to comprehend – let alone recreate. Inventing a machine that sees like we do is a deceptively difficult task, not just because it’s hard to make computers do it, but because we’re not entirely sure how we do it in the first place.What actually happens is roughly this: the image of the ball passes through your eye and strikes your retina, which does some elementary analysis and sends it along to the brain, where the visual cortex more thoroughly analyzes the image. It then sends it out to the rest of the cortex, which compares it to everything it already knows, classifies the objects and dimensions, and finally decides on something to do: raise your hand and catch the ball (having predicted its path). This takes place in a tiny fraction of a second, with almost no conscious effort, and almost never fails. So recreating human vision isn’t just a hard problem, it’s a set of them, each of which relies on the other.

Well, no one ever said this would be easy. Except, perhaps, AI pioneer Marvin Minsky, who famously instructed a graduate student in 1966 to “connect a camera to a computer and have it describe what it sees.” Pity the kid: 50 years later, we’re still working on it.

Serious research began in the 50s and started along three distinct lines: replicating the eye (difficult); replicating the visual cortex (very difficult); and replicating the rest of the brain (arguably the most difficult problem ever attempted).

To see

Reinventing the eye is the area where we’ve had the most success. Over the past few decades, we have created sensors and image processors that match and in some ways exceed the human eye’s capabilities. With larger, more optically perfect lenses and semiconductor subpixels fabricated at nanometer scales, the precision and sensitivity of modern cameras is nothing short of incredible. Cameras can also record thousands of images per second and detect distances with great precision.

An image sensor one might find in a digital camera.

Yet despite the high fidelity of their outputs, these devices are in many ways no better than a pinhole camera from the 19th century: They merely record the distribution of photons coming in a given direction. The best camera sensor ever made couldn’t recognize a ball — much less be able to catch it.

The hardware, in other words, is severely limited without the software — which, it turns out, is by far the greater problem to solve. But modern camera technology does provide a rich and flexible platform on which to work.

To describe

This isn’t the place for a complete course on visual neuroanatomy, but suffice it to say that our brains are built from the ground up with seeing in mind, so to speak. More of the brain is dedicated to vision than any other task, and that specialization goes all the way down to the cells themselves. Billions of them work together to extract patterns from the noisy, disorganized signal from the retina.

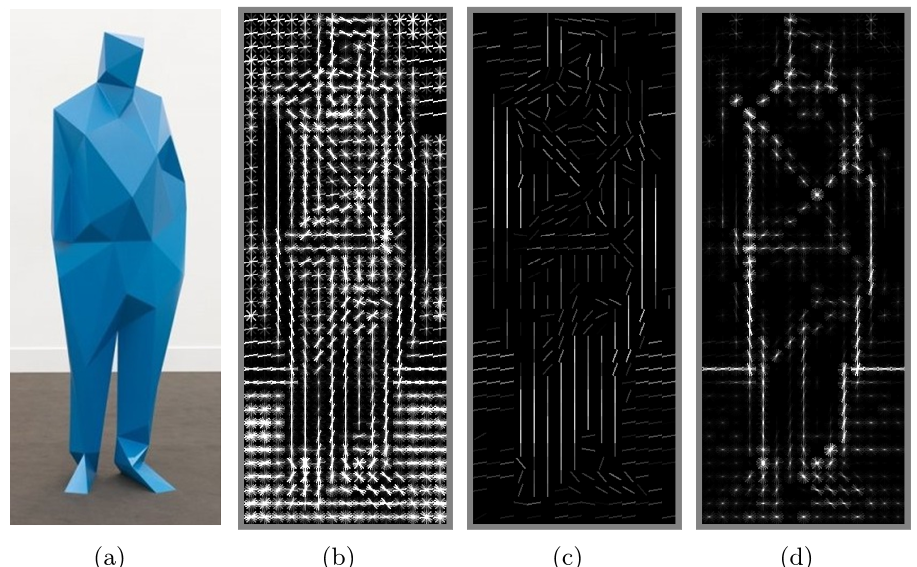

Sets of neurons excite one another if there’s contrast along a line at a certain angle, say, or rapid motion in a certain direction. Higher-level networks aggregate these patterns into meta-patterns: a circle, moving upwards. Another network chimes in: the circle is white, with red lines. Another: it is growing in size. A picture begins to emerge from these crude but complementary descriptions.

A “histogram of oriented gradients,” finding edges and other features using a technique like that found in the brain’s visual areas.

Early research into computer vision, considering these networks as being unfathomably complex, took a different approach: “top-down” reasoning — a book looks like /this/, so watch for /this/ pattern, unless it’s on its side, in which case it looks more like /this/. A car looks like /this/ and moves like /this/.

We can barely come up with a working definition of how our minds work, much less how to simulate it.

For a few objects in controlled situations, this worked well, but imagine trying to describe every object around you, from every angle, with variations for lighting and motion and a hundred other things. It became clear that to achieve even toddler-like levels of recognition would require impractically large sets of data.

A “bottom-up” approach mimicking what is found in the brain is more promising. A computer can apply a series of transformations to an image and discover edges, the objects they imply, perspective and movement when presented with multiple pictures, and so on. The processes involve a great deal of math and statistics, but they amount to the computer trying to match the shapes it sees with shapes it has been trained to recognize — trained on other images, the way our brains were.

What an image like this one above (from Purdue University’s E-lab) is showing is the computer displaying that, by its calculations, the objects highlighted look and act like other examples of that object, to a certain level of statistical certainty.

Proponents of bottom-up architecture might have said “I told you so.” Except that until recent years, the creation and operation of artificial neural networks was impractical because of the immense amount of computation they require. Advances in parallel computing have eroded those barriers, and the last few years have seen an explosion of research into and using systems that imitate — still very approximately — the ones in our brain. The process of pattern recognition has been sped up by orders of magnitude, and we’re making more progress every day.

To understand

Of course, you could build a system that recognizes every variety of apple, from every angle, in any situation, at rest or in motion, with bites taken out of it, anything — and it wouldn’t be able to recognize an orange. For that matter, it couldn’t even tell you what an apple is, whether it’s edible, how big it is or what they’re used for.

The problem is that even good hardware and software aren’t much use without an operating system.

For us, that’s the rest of our minds: short and long term memory, input from our other senses, attention and cognition, a billion lessons learned from a trillion interactions with the world, written with methods we barely understand to a network of interconnected neurons more complex than anything we’ve ever encountered.

The future of computer vision is in integrating the powerful but specific systems we’ve created with broader ones.

This is where the frontiers of computer science and more general artificial intelligence converge — and where we’re currently spinning our wheels. Between computer scientists, engineers, psychologists, neuroscientists and philosophers, we can barely come up with a working definition of how our minds work, much less how to simulate it.

That doesn’t mean we’re at a dead end. The future of computer vision is in integrating the powerful but specific systems we’ve created with broader ones that are focused on concepts that are a bit harder to pin down: context, attention, intention.

That said, computer vision even in its nascent stage is still incredibly useful. It’s in our cameras, recognizing faces and smiles. It’s in self-driving cars, reading traffic signs and watching for pedestrians. It’s in factory robots, monitoring for problems and navigating around human co-workers. There’s still a long way to go before they see like we do — if it’s even possible — but considering the scale of the task at hand, it’s amazing that they see at all.