Humans are pretty good at ballparking distances, even with one eye closed — but it turns out computer vision systems have a hard time with it. Researchers hope to fix that, or at least make robots a little more robust, by teaching them to navigate a space without the benefit of stereo vision — in zero gravity, to boot.

The reason we’re so good at it is that we’ve built up a huge library of knowledge about the objects and spaces we tend to inhabit: trees are about this big, and don’t grow indoors; TVs are flat and about this big, and tend to be near walls; doors are about this big and you can see the next room through them; etc, etc. It’s all very elementary to us but we often forget how long it took us to learn all that stuff (and how easy it is to unlearn when one is tired or drunk).

Computer vision systems tend to rely solely on the facts: the depth information from stereo cameras, usually, complemented by a limited object-recognition engine that can pick out a box from the table it’s sitting on, or a knob from the door itself.

But that assumes everything is working properly. What if one of the cameras is taken out of commission by a system error or a leaf blowing onto it? How will it safely navigate if it relies on having both 100 percent of the time? This applies not just to random robots, but to self-driving cars and other devices.

An experiment backed by the European Space Agency and Delft University of Technology investigates the possibility of robots teaching themselves how to get around their environment, effectively, with one eye closed.

“It is a mathematical impossibility to extract distances to objects from one single image, if the object has not been encountered before,” said Delft’s Guido de Croon in an ESA news release. “But if we recognize something to be a car, then we know its physical characteristics, and we can use that information to estimate its distance from us. A similar logic is what we wanted the drone to learn during our experiment.”

“It is a mathematical impossibility to extract distances to objects from one single image, if the object has not been encountered before,” said Delft’s Guido de Croon in an ESA news release. “But if we recognize something to be a car, then we know its physical characteristics, and we can use that information to estimate its distance from us. A similar logic is what we wanted the drone to learn during our experiment.”

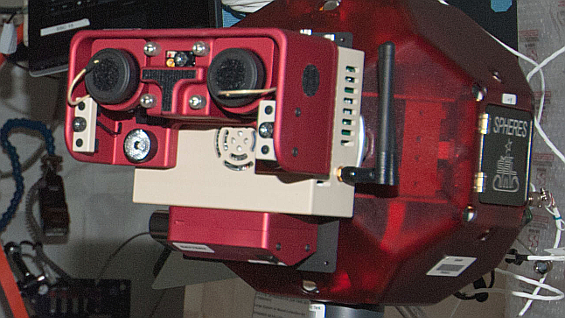

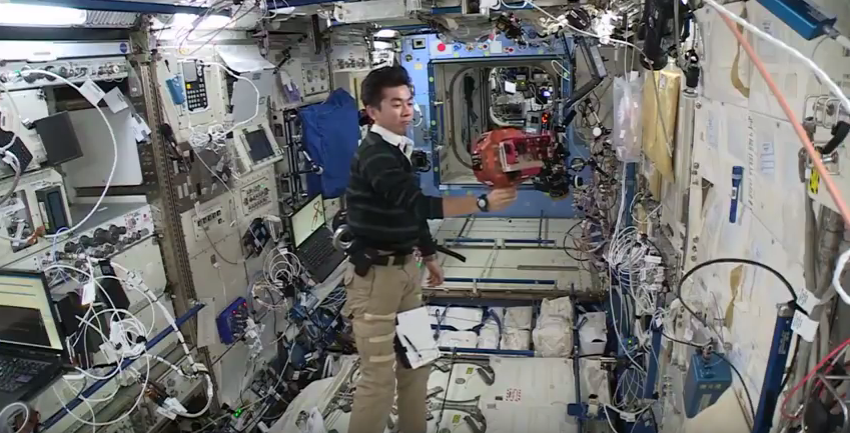

The experiment took place on the International Space Station. They equipped a SPHERES (Synchronized Position Hold Engage and Reorient Experimental Satellites, essentially round, multi-purpose drones that work in microgravity) with stereo cameras, and had it roam around the Japanese ISS module. It took measurements with both “eyes,” but also ran a machine-learning task using just one, attempting to keep track of the module’s features and establish distances.

Here’s the raw feed from one of the runs:

For instance, it would see with the stereo cameras that a hatch was 4 feet away and 2 feet wide — and at the same time, the single-camera stream would attempt to associate the image it saw with that information — a certain shape, growing larger at a certain rate, that sort of thing.

The researchers could only dedicate a little time to the experiment — it has to be run by astronauts, after all, and they’re busy people — and the initial run was a mixed bag with several technical difficulties. But the technique has promise, and the single-camera estimate of distance got to be pretty good, though not good enough to navigate by just yet.

They presented their findings today at the International Aeronautical Conference; you can read the paper here.