Chrisfino Kenyatta Leal never thought he would end up in prison. What he did envision, he tells me, was dying before the age of 25 or 30.

“I saw so many people around me dying at such a young age that my long-term vision just wasn’t in focus,” Leal tells me. “I was just focused on what was right in front of me.”

In 1994, Leal was pulled over by the police for “being black and driving a nice car in an area where they probably thought I shouldn’t have been,” he says. A friend of Leal’s was in the car, and the police found a gun on him. Even though the friend testified that it was his gun, Leal was charged for constructive possession. It was his third strike. Sentence: 25 years to life.

Nineteen years later, at the age of 44, Leal walked out of prison. Against all odds, he made his way into the tech industry. You could say he’s one of the lucky ones.

Chrisfino Kenyatta Leal

Chrisfino Kenyatta Leal

“I saw so many people around me dying at such a young age that my long-term vision just wasn’t in focus.”

When you hear about a “pipeline problem” in tech, it is often in regards to the lack of diversity in the Silicon Valley tech ecosystem. The crux of the pipeline argument is that there are not enough underrepresented minorities and women pursuing knowledge in computer science and programming.

Tech companies like Apple, Google and Facebook love to cite the so-called pipeline problem as the reason for the discrepancy between underrepresented minority groups and white people among their staff. Just this month, Facebook’s global head of diversity once again blamed the company’s meager amount of black and brown employees on a lack of available talent. This was met with criticism and anger among diversity and inclusion advocates across the tech industry.

While the pipeline is certainly a small part of the problem, there are other elements that impact diversity in tech — inclusion and belonging. It’s one thing to hire underrepresented minorities, but it’s another thing to make them feel included and wanted. What often results is the so-called “leaky bucket” phenomenon, which describes people of color entering a space and eventually leaving because of the unconscious biases they experience at the hands of their colleagues.

In the past year, the tech industry has started addressing unconscious bias in the workplace. Facebook, for example, has even gone so far as to build a resource site called “Managing Unconscious Bias,” with the idea that other tech companies can tap into Facebook’s best practices.

We have a criminal justice system that is inherently infected with racial bias.— Ana Zamora, criminal justice policy director, ACLU of N. California

What’s missing from the conversation, however, is the other pipeline — the criminal justice system. Systemic racism is at the root of this multi-faceted, other pipeline. It results in the disproportionate amount of underrepresented minorities, particularly black people, ending up behind bars — sometimes directly from the classroom.

Across the nation’s public schools, there are more than 43,000 school resource officers, which includes career law enforcement officers with the authority to arrest children and send them to jail, according to a National Center for Education Statistics report. This school-to-prison pipeline disproportionately affects young black and brown people.

“School discipline issues are still an important driver,” Ana Zamora, criminal justice policy director at the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California, tells me. “Regressive and highly punitive school discipline policies have a tendency to funnel certain youth into a certain direction, and that’s the basis of the school-to-prison pipeline.”

Meanwhile, the lack of data makes it nearly impossible to quantify the effects of systemic racism on the criminal justice system. As it stands right now, there is no way of measuring and demonstrating patterns.

“I believe we have a criminal justice system that is inherently infected with racial bias, and that is a huge contributor. Whether or not it’s a pipeline, I don’t know, but it’s a huge contributor,” she says. “We’ve had some really highly punitive laws in place and tools for law enforcement to ensure certain people are going to be incarcerated.”

Zamora says it’s difficult to identify what is going on because we don’t actually have the information and so we can’t determine the patterns. There is a lack of data in the criminal justice system. In fact, there is barely any at all.

“We can’t analyze how and why law enforcement are making certain decisions or why certain people are charged with a felony and other people are charged with a misdemeanor for the exact same crime,” Zamora says. “This is information we need access to.”

The criminal justice system plays a significant, behind-the-scenes role in the lack of diversity in the tech industry today. And we can’t efficiently tackle diversity and inclusion in tech without first examining the criminal justice system.

The number of black people under the control of the correctional system is staggering.

Today, there are more African-American adults under correctional control — in prison, jail, on probation or on parole — “than were enslaved in 1850, a decade before the Civil War began,” writes legal scholar and author Michelle Alexander in her book “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness,” citing numbers by the Pew Charitable Trust report “the Pew Center on the States.”

In the late 1950s, segregationists started to use law-and-order rhetoric geared toward getting white people to oppose the civil rights movement. They were responsible for the narrative that civil rights protests were a criminal act rather than a political one, their argument being that the protests were contributing to the spread of crime.

While there was an increase in crime during this time, the reasons for it were complex. The Baby Boom generation accounted for a spike in young men in the 15-to-24 age group, which has historically been responsible for most crimes. Alexander refers to this period, and the mass incarceration that has resulted from it, as “the new Jim Crow.”

“The surge of young men in the population was occurring at precisely the same time that unemployment rates for black men were rising sharply, but the economic and demographic factors contributing to rising crime were not explored in the media,” Alexander writes in her book (page 41). “Instead, crime reports were sensationalized and offered as further evidence of the breakdown in lawfulness, morality, and social stability in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement.”

After the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which formally ended discrimination in public spaces, employment, voting and education, the public focus shifted to crime. When riots erupted after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, the racial imagery in the media associated with them helped to fuel the segregationists’ argument that civil rights for blacks led to an increase in crime. Meanwhile, between the 1960s and 1980, conservatives began to question welfare, pitting hard-working white people against black people who didn’t want to work.

“The not-so-subtle message to working-class whites was that their tax dollars were going to support special programs for blacks who most certainly did not deserve them,” Alexander writes in “The New Jim Crow” (page 48).

The turning point came in 1971 when President Richard Nixon called for a war on drugs and referred to illegal drugs as “public enemy number one.” Crime and welfare ultimately became the major themes of Ronald Reagan’s presidential campaign in 1980, which used racially coded rhetoric and strategies.

Demonstrators protesting student segregation, 1963. (National Archive/Newsmakers) Kids attacked during segregation protest, May 1963, Birmingham. (Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images) President Lyndon Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act, July 2, 1964. (Universal History Archive/Getty Images) Martin Luther King Jr., Philadelphia, 1965 (Rolls Press/Popperfoto/Getty Images) Riot aftermath following Martin Luther King Jr. assassination. (Lee Balterman/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

President Ronald Reagan followed through with Nixon’s desires. Despite the fact that drug use was on the decline, in 1982 he officially declared a war on drugs, stating that illicit drugs were a threat to national security (“The Politics of Injustice: Crime and Punishment in America” by Katherine Beckett and Theodore Sasson, page 163).

Between 1980 and 1984, the FBI’s anti-drug funding increased from $8 million to $95 million, according to the Budget of the U.S. government in 1990 (Katherine Beckett, Making Crime Pay: Law and Order in Contemporary American Politics, page 53). In contrast, funding for agencies in charge of drug treatment, prevention and education was reduced. The budget for the National Institute on Drug Abuse, for example, went from $274 million in 1981 to $57 million in 1984, according to 1992 data from the U.S. Office of the National Drug Control Policy.

Meanwhile, in the early 1980s, inner-city communities were suffering from an economic collapse. Black inner-city communities were the ones that felt the impacts of globalization and deindustrialization the most.

As late as 1970, more than 70 percent of blacks working in metropolitan areas held blue-collar jobs (William Julius Wilson, When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor). By 1987, the employment rate for black men dropped to 28 percent (John Kasarda, “Urban Industrial Transition and the Underclass,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 501, no. 1 [1990]).

In 1985, a few years after Reagan announced the war on drugs, crack cocaine hit the streets. Investigations have since suggested that the government played a role in embedding crack on the streets of inner-city black neighborhoods, as described in Alexander Cockburn and Jeffrey St. Clair’s book, “Whiteout: The CIA, Drugs and the Press” and by Michelle Alexander.

“The CIA admitted in 1998 that guerrilla armies it actively supported in Nicaragua were smuggling illegal drugs into the United States — drugs that were making their way onto the streets of inner-city black neighborhoods in the form of crack cocaine,“ Alexander writes in her book (page 6).

The lack of legitimate job opportunities in low-income black neighborhoods, combined with the infusion of illegal drugs into these neighborhoods, created an incentive to sell drugs. Reagan’s administration jumped on the opportunity to publicize the crack cocaine epidemic, sensationalizing its emergence. These sensationalized media campaigns continued to 1989.

During that time, the racism against blacks was fueled by the job loss created by the economic collapse and the crack epidemic that struck the streets of black neighborhoods. With that in mind, white people were in support of “getting tough on crime” initiatives, as well as anti-welfare measures. The war on drugs ultimately gave white people an easy way to discriminate against blacks and express hostility without being accused of racism.

This general attitude of getting tough on problems affecting people of color started in the 1960s, and it was mostly conservatives engaging in that sort of rhetoric. But by the late 1980s, Democrats hoping to take political control from Republicans began to participate. In order to do that, they had to win back the swing voters who were leaning toward the Republican Party because of its stance on crime and drugs. With both parties on board the “get tough on crime” train, jail and prison populations dramatically increased.

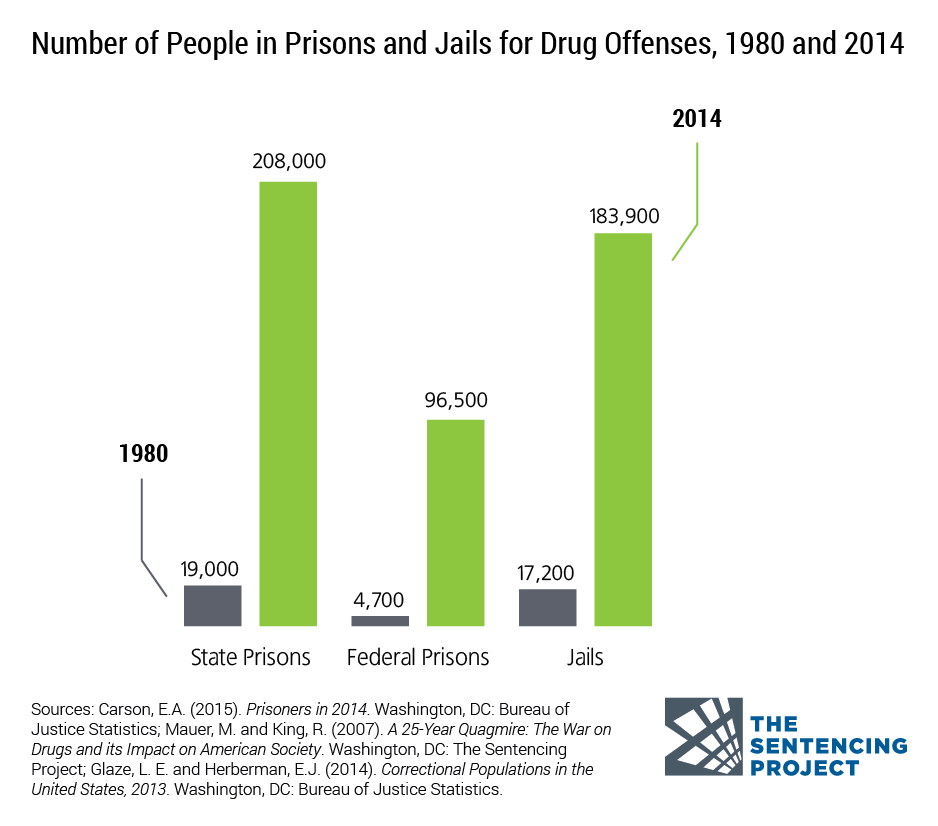

The number of people incarcerated for drug crimes in the U.S. went from 41,000 in 1980 to almost 500,000 in 2014, according to the Sentencing Project. The increase in the prison population disproportionately affected the African-American community, with one-fourth of young black men between the ages of 20-29 under the control of the criminal justice system in 1990, according to the Sentencing Project.

And according to a 2000 survey by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 6.4 percent of whites, 6.4 percent of blacks and 5.3 percent of Hispanics used illegal drugs. But despite these similar rates of drug use, black men are sent to state prison on drug charges at more than 13 times the rate of white men. There is a reason for the disparity.

When Bill Clinton was running for president, he said he would never let any Republican be perceived as tougher on crime than he was. During his first term in office, he signed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994.

The bill included the three-strikes provision that mandated a life sentence in prison without the possibility of parole for offenders convicted of three felony crimes or more. That $30 billion bill also introduced a number of new federal capital crimes and authorized more than $16 billion for state prison grants and the expansion of state and local police forces.

The Clinton administration’s policies on crime led to the largest increases in federal and state prison inmates of any American president in history, according to the Justice Policy Institute.

President Clinton then turned his attention to welfare policies, signing the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act. The bill imposed a five-year limit on welfare assistance, as well as a lifetime ban on eligibility for food stamps and welfare for anyone convicted of felony drug use or possession, including possession of marijuana.

Clinton also made it easier for the government to refuse public housing to anyone with a criminal history. As a result, millions of poor people, especially the racial minorities targeted by the drug war, ended up homeless. Someone with a criminal record also has limited eligibility for federal student aid and must indicate if they have a felony conviction on their record when applying for jobs.

In 2002, more than 2 million people were behind bars in the U.S., according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Additionally, as a result of Clinton-era policies, millions more were still held prisoner of the criminal justice system once they were released by way of discrimination in employment, housing and access to education. And given the legal, discriminatory nature of society in the U.S., recidivism rates remain high.

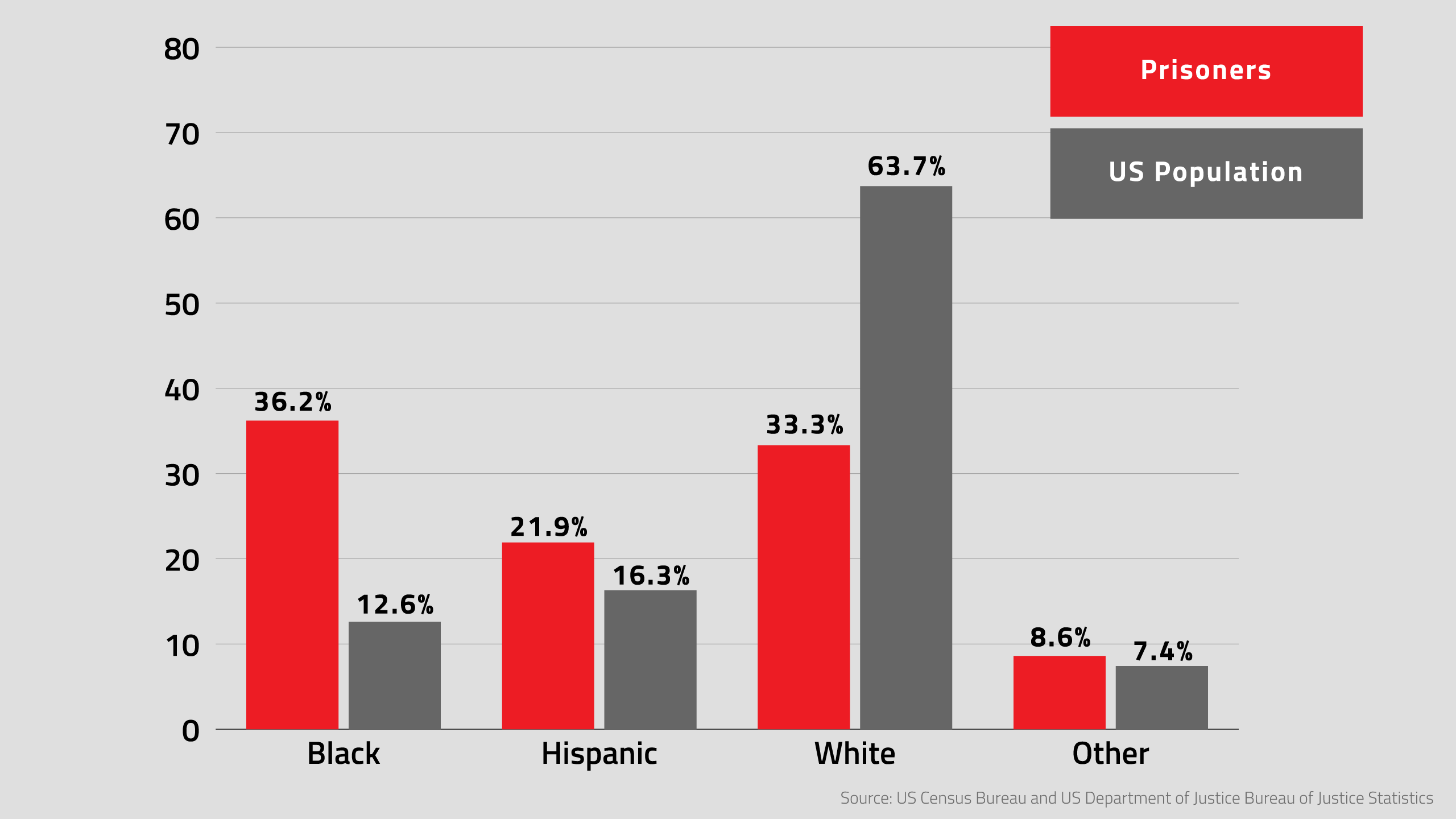

Today, black and Latino people comprise about 1.5 million of the total 2.2 million people incarcerated in the U.S. adult correctional system, or 67 percent of the prison population, while making up just 37 percent of the total U.S. population, according to the Sentencing Project. That’s because black people are incarcerated at nearly six times the rate of white people.

But black people aren’t incarcerated at higher rates than white people because they’re committing more crimes. Five times as many white people are using drugs as black people, for example, but African-Americans are sent to prison for drug offenses at 10 times the rate of white people.

Also, blacks serve almost as much time in prison for a drug offense (58.7 months) as white people do for a violent offense (61.7 months). There are millions of black adults who are thus unable to explore opportunities in tech, whether they want to or not.

Meanwhile, youth of color make up over 63 percent, or 22,669, of those committed to juvenile facilities, according to 2013 data from the Easy Access to the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement. That’s not including those who were sent to adult jails and prisons. As of 2014, there were 5,235 youth in adult jails, according to data analyzed by the Sentencing Project. Nationwide, blacks represent 37 percent of youths in jails, which brings that to 1,936 young black men in adult jails.

At the same time, young people of color who are impacted by the criminal justice system early in life are more likely to end up incarcerated later in life, are at risk of sexual assault and abuse in these juvenile centers and suffer from mental health issues (almost 70 percent) according to Child Trends Data Bank.

As is the purpose of any racial caste system, the function of mass incarceration is to define what race is, and it accomplishes the same thing that Jim Crow laws achieved: segregation of black people from mainstream society.

As Alexander writes, slavery in America defined black people as slaves, the Jim Crow era of discriminatory laws defined blacks as second-class citizens and the era of mass incarceration — our present-day racial caste — defines blacks as criminals.

In the U.S., the tech industry employs more than 6.7 million people and is a big part of the country’s economy. It has grown consecutively for the last five years, with tech today accounting for 7.1 percent of the U.S. GDP and 11.6 percent of total overall payroll in the private sector, according to nonprofit IT trade association CompTIA. This year, employment in the tech industry hit its highest growth rate in more than a decade.

Black people make up just 2 percent of the employee populations at Facebook, Google and Dropbox. We know this because, in the last couple of years, tech companies have become more willing to release their EEO-1 diversity data and put out diversity reports. Another recent trend has been the hiring of heads of diversity and inclusion. Unfortunately, these efforts seem to be falling short, as not much improvement has been made in terms of representation of people of color at tech companies.

Meanwhile, the number of underrepresented minorities at the board level is even lower. In 2014, there were only three black people and one Hispanic person sitting on the board of directors across 20 major tech companies, according to a survey by the Rev. Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow PUSH Coalition. Jackson has played a big role in the push for diversity in tech by persistently demanding that companies release diversity data and commit to the hiring of underrepresented minorities at all levels of the company, including the board of directors.

Jackson and his organization have committed to this push because diversity in tech, he says, is the civil rights issue of our time.

“One civil rights movement was to end legal slavery,” Jackson told me in April. “Another was to end legal Jim Crow and the lynching season. That was a civil rights movement of that day. Another was the right to vote. You can abolish slavery, get rid of Jim Crow, and vote, and be broke and impoverished without access to capital, industry and technology, and deal flow and relationships. This is the civil rights of our time: access to capital, access to computers, how to make them, how to sell them.”

The absence of black people from tech is not a function of lack of interest, knowledge, skill or drive. Instead, there are a couple of issues at hand, both of which relate to systemic racism and discrimination. First is the fact that the tech industry is underutilizing the diverse talent pool.

“While there is some truth to the ‘pipeline’ theory and anxiety over the ability of the US educational system to provide a sufficiently large, well trained, and diverse labor pool, there are additional factors at play,” the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s latest report, Diversity In High Tech, states.

“For example, about nine percent of graduates from the nation’s top computer science programs are from underrepresented minority groups. However, only five percent of the large tech firm employees are from one of these groups. This presents the unlikely scenarios that either major employers in the field are unable to attract four out of nine underrepresented minority graduates from top schools or almost half of the minority graduates of top schools do not qualify for the positions for which they were educated.”

We’re fighting really systemic racism that’s been built into the fabric of not just these companies, but our nation in general.

Second is the institutionalized racism that has led to millions of people of color disappearing into prisons and jails, locked away for drug crimes that, when committed by white people, are largely ignored.

As a result, underrepresented minorities are either locked up behind bars or caught in the grasp of this country’s criminal justice system thanks to institutionalized racism, or they’re locked out of the tech industry thanks to prejudice and several covert acts of individual racism.

“We’re fighting really systemic racism that’s been built into the fabric of not just these companies, but our nation in general,” Black Girls Code founder Kimberly Bryant told me in February.

Being under the control of the criminal justice system negatively impacts one’s life chances and makes it legal to be discriminated against when applying for jobs, housing and loans. As a result, thousands of young people of color are missing out on opportunities to participate in traditional school, hackathons, coding schools and internships at tech companies.

To ensure that everyone has a fair chance to get into the tech industry, we need to focus on the other pipeline — the pipeline that leads to a disproportionate number of black people and other minorities ending up in prison.

Originally sentenced to 25 years to life in prison, Leal served 19 years of his sentence — first at Pelican Bay and then at San Quentin — thanks to both the enactment and amendment of California’s Three Strikes sentencing law.

Leal first entered the criminal justice system in 1991, when he pled guilty to two counts of robbery for stealing money from a safe and a cash register at one restaurant. That’s two counts for one robbery. Leal was released in 1994, which is when the Three Strikes Law was enacted, so those two counts for one robbery meant two strikes.

“I always had hope that I would get out,” Leal says. “That was something that stayed really, really clear in my head. I could see the light at the end of the tunnel. I didn’t care how much time they gave me or what anybody else said. I always believed that I was going to get out. I just didn’t know when. So it was really all about preparing myself for that opportunity so that when it did come, I’d be ready.”

In 2010, 16 years into his life sentence with no sign of getting out of prison anytime soon, Leal helped start The Last Mile inside San Quentin with Transmedia Capital General Partner Chris Redlitz. The Last Mile teaches people how to code and start their own companies. It partners with tech companies to help place participants in internships and paid roles once they’re released from prison. Leal graduated with the first cohort of men in 2012.

“When we were finishing our first class and we had guys who were preparing to get out, I went to some of the people in my portfolio and said, ‘We’ve got these guys. I think they’re prepared, but they’ve been in prison over 15 years and they don’t really know technology and they haven’t had a job in a long time’ and I really asked a favor of [tech companies] to participate in our internship program,” Redlitz tells me.

The former prisoners ended up excelling once they joined these tech companies. Leal is one of those employees Redlitz is referring to.

In 2012, California voters approved Proposition 36, which led to the amendment of the three strikes provision of the 1994 crime bill. Two main changes made to the law were that the third strike needed to be a serious or violent felony and that those currently serving a third-strike sentence could petition the court for reduction of their term to a second-strike sentence — if they would have been eligible for second-strike sentencing under the new law.

For Leal, that meant that he could meet with a judge for potential re-sentence. In 2013, Leal met with the same judge who originally sentenced him to 25 years to life. The judge re-sentenced Leal to seven years and a week later, Leal was released from prison.

“That was probably the best feeling I’ve ever felt,” Leal tells me. “It’s amazing. It’s one thing to be in prison, but to be in prison with a life sentence — I can’t even begin to explain how tough that is because you could literally die in prison. Who the hell wants to die in prison? There was the uncertainty of not knowing when you’re going to get out, which was really hard, so when I did walk out of there, it was probably one of the best moments of my life.”

While at The Last Mile inside San Quentin, Leal met RocketSpace CEO Duncan Logan, a friend of Redlitz’s, who says he had never been to a correctional facility before. RocketSpace is a co-working accelerator that has housed startups like Uber, Spotify and Leap Motion.

“I actually went in before the demo day to do some coaching,” Logan tells me. “That was when it kind of struck me. It just shattered all of my illusions of what I thought I would see or experience.” He tells me he sees the criminal justice system in a different way. Before, he was in the bucket of “if we remove [criminals], it’ll be a better place,” he tells me. “I was in a fairly common misunderstanding of what was going on with crime. Certainly in a total misunderstanding of what a correctional system is and what it could be — I think I’ve gone through a total transition on that.”

When demo day came around, Logan returned to San Quentin and was impressed by Leal’s presentation. Logan told Leal that if he ever got out, he would hire him. He kept his word. Of Leal, Logan says: “He’s achieving more than most of the staff sitting here.”

Leal joined RocketSpace in 2013, a year after he was released from San Quentin. Since then, he’s gone from moving furniture at RocketSpace to setting up IT equipment and doing some programming as RocketSpace’s manager of campus services. In transitioning from prison to the tech industry, Leal has seen a number of parallels.

It’s one thing to be in prison, but to be in prison with a life sentence — I can’t even begin to explain how tough that is because you could literally die in prison.

“One of the things that I noticed immediately about RocketSpace and this whole tech hub at RocketSpace is there’s a lot of energy there,” Leal says. “In prison there’s a lot of energy. The big difference is that so much of the energy in prison is chaotic. Inside RocketSpace, everything is focused on these goals and trying to get this product to market, raise money, be successful.

“So I think that inside prisons there’s this attitude of just making the most of whatever you have to work with. In prison, it’s all about the minimal viable product. There’s a parallel there as well. I think that one of the biggest parallels I’ve found about the entrepreneurship and tech world is that failure isn’t a bad thing. Failure is actually a good thing. You can learn things from failure.”

People in the tech industry have made some steps toward creating opportunities for those who have gone through the criminal justice system. It’s time to focus on what happens before people enter the criminal justice system.

In total, black people are more likely than white people in America to be arrested and, once arrested, blacks are more likely to be convicted, according to The Sentencing Project. And once convicted, blacks are more likely than whites to face harsh sentences.

Technology and data could play a big role in dismantling the system that leads to a disproportionate number of black men ending up in prison.

According to the ACLU’s Zamora, there is a lack of uniform data collection on the various phases of the criminal justice system.

“Everything from when people are stopped to all the way through a trial, as well as how decisions are made throughout the process and how those decisions are affecting different communities,” Zamora says. “So, there’s a big data void in criminal justice.”

With the help of technology, there could be a lot more transparency to the criminal justice system simply by surfacing the data the government does have.

Right now, a lot of people feel like there’s a bit of a black box around what’s going on in local police forces and in the system at large, Justin Erlich, special assistant attorney general, in the office of Attorney General Kamala Harris, tells me. That’s because, Erlich says, a lot of the tech and infrastructure that criminal justice agencies use are pretty old.

“It’s not necessarily that people are trying to hide or not share the data as much as it’s actually amazingly difficult, manually, to get out and extract data,” Erlich says. “I think that making sure we are all working together to get modern technology into all of these agencies is critical for us to really then be able to use APIs or extractions of the cloud to analyze and research what is going on.”

Erlich led the team that recently relaunched OpenJustice, an effort by the California Department of Justice to make law enforcement data more transparent. But in order to make serious strides, and move toward real-time criminal justice data reporting and better policies, Erlich says, we’ll need more public-private partnerships between the government and leading tech companies.

Getting more technology and the tech industry involved in criminal justice efforts pays dividends.

So far, Erlich says there has been some high-level support from companies like Facebook, for example, but a lot more support is needed.

Technology could also be helpful with better understanding how to reduce the number of those entering the criminal justice system through pre-trial and bail reform.

“Instead of locking people up, we can use technology to better keep track of folks, so they don’t have to enter the system in the first place,” Erlich says. “And on the backend, we can start training folks that will help diversify the technology pool. That’s not just simply from a demographic perspective but also from a worldview perspective. I think it’s important that a lot of people who end up touching the system are then put in places where they can take action to reform it.”

Not everybody goes through the criminal justice system, so there’s a lot of value in sharing that perspective with others, Erlich says.

“Getting more technology and the tech industry involved in criminal justice efforts pays dividends both for society itself but also directly to the tech industry,” Erlich says.

Meanwhile, the White House recently challenged artificial intelligence experts to help reform the criminal justice system. Speaking at a Computing Community Consortium workshop, Lynn Overmann, head of the White House Police Data Initiative, said AI and data analytics could be useful in improving questions on parole screenings, analyzing police body camera footage and in analyzing criminal justice data. Oakland, California, for example, has seen a drop in the use of force by both police and citizens since deploying body cameras.

That said, inserting technology into the criminal justice system doesn’t necessarily mean good will come from it. In certain states throughout the country, courts are using algorithmic software to predict the likelihood of someone committing a crime in the future. In analyzing risk scores from Broward Country, Florida, for instance, the investigative team at ProPublica found that the software used in the sentencing process is biased against blacks. However, the private company behind the software could work to overcome this bias if they decided to implement updates.

By reforming the criminal justice system, there’s also an opportunity to fill the so-called labor shortage in the tech industry. Through programs like The Last Mile and other proactive approaches to teaching tech skills to former prisoners, the tech industry could gain access to untapped talent while also tackling diversity.

“Unfortunately, we know we’ve sort of got two distinct diversity issues,” Erlich says. “One is in the tech sector. We don’t have the diverse labor set that we would hope for many reasons. Similarly, unfortunately, also again for many societal reasons, those who are entering the criminal justice system are not diverse in a different way, which is, they’re disproportionately minority and African-American and I think both of those results are an example of broader societal issues that we’re struggling with.

And they are sort of an opportunity for us to really focus on addressing both of those, which is how can we use technology better to understand how to reduce those entering the system.”

Addressing the problems of inequity and racial justice in the criminal justice system would allow for more opportunities for communities of color to thrive in many different ways.

”The criminal justice system really embodies a lot of our problems with race in our country,” Zamora says. “So if we can fix that, I do think we’ll see a lot of positive changes.”

Featured image by Bryce Durbin / photos by Yashad Kulkarni