2014 is starting off with a bang for hardware. The $3.2B acquisition of Nest, a four year old company, is great news for makers. The question is, then, should you be starting a hardware company rather than the next mobile app? In previous columns we covered the first steps: from prototype to production as well as early stage financing. Let’s now look into another trap: distribution.

Software vs. Hardware

When you get traction with software, you fire up new servers and scale your infrastructure. It is fast and cheap. And traction alone can get you funding. With hardware, traction is sales, or at least demand. Unfortunately, sales of physical things happen months after production. How do you finance it? How many units should you build? Can you afford to lose money or time?

There are two persistent myths for hardware startups. The first is that the end game is selling at big box retailers like Wal-Mart or Best Buy. The second is that once your amazing gizmo is on the shelves it will sell itself. Those two ideas are dangerous.

Wal-Mart is a problem because servicing retailers is not easy. And the bigger they are, the more cash and time you will need. The Startup Genome project documented that the number one cause of failure for startups was premature scaling. This is even truer for hardware. So before working with larger chains, startups had better get their act together on a smaller scale. It is also questionable whether your product is suitable at all for big box retailers, where your margins are lower and costs higher.

The second is a variation of “build it and they will come.” Sadly, retailers are not in the business of creating demand. You are. If your distribution exceeds the demand you created, it will result in unsold inventory. And we all know what that means.

Crossing the retail chasm

Hardware projects on Kickstarter belong to the “technology” and “design” categories. By the end of last year, 3,009 of them had been successfully funded. 384 (13%) were between $100,000 and one million dollars, and only 16 (0.5%) were above a million. And that is among projects funded successfully! If you can’t demonstrate demand with the novelty and tech-hungry kickstarted crowd, it is questionable if your product will have enough demand, and if you’re the right team to sell it (we’re not even talking about building it). Some say you can sell a thousand of anything on Kickstarter, but even that is easier said than done.

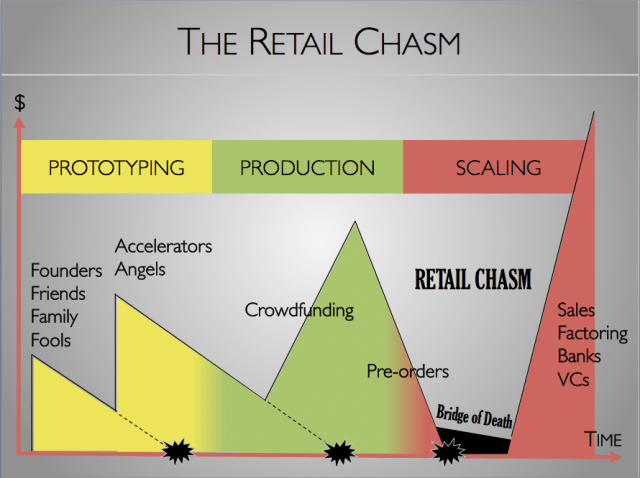

Now let’s assume your kickstarted project succeeded (over $100k). Once it’s over, your monthly pre-sales are likely to be in the range of 1/20th of your crowdfunding total. That means if you got $200,000 on Kickstarter now your sales are at $10,000/month. Obviously not enough to support a team long term. You are thus entering the “retail chasm” or “bridge of death” until demand and distribution pick up. Financing this gap is difficult as innovators (the Kickstarter crowd) bought your product but you are still far from the mainstream. Early adopters might be waiting for your product to be ready but will only pay later, if they hear about it.

Two key aspects of crossing the chasm between a crowdfunding campaign (where you get paid up to a a year before shipping) to retail (where you might need to finance up to 6 months of inventory) is demand creation and distribution.

Positioning and demand creation

Demand creation is a result of your positioning (which covers your target user profile, pricing and branding) as well as your media, community and marketing activities. If your products are consistently in demand and fly off the shelves (even if you have limited shelf space), you will find ways to finance growth.

Venture funding will not solve the problem of selling products at a loss, it will just dig a bigger grave faster. Learn how to sell profitably before you scale.

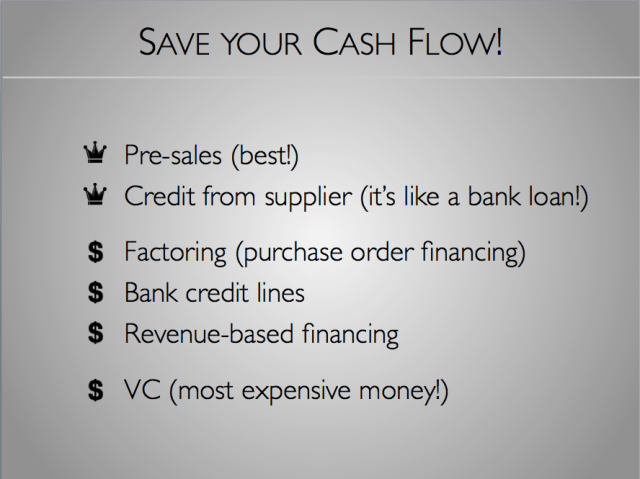

Once you’ve crossed the bridge and demonstrated demand, financing becomes a lot easier. From factoring to bank loans or venture capital, money will beat a path to your door!

Distribution: when and how to scale?

You need distribution, but not any distribution. And not in any order. Among the options are direct sales online and selling via others either online or offline. Each channel has to be evaluated carefully and larger retailers might have to wait for a later phase. Build your retail skills and more demand first.

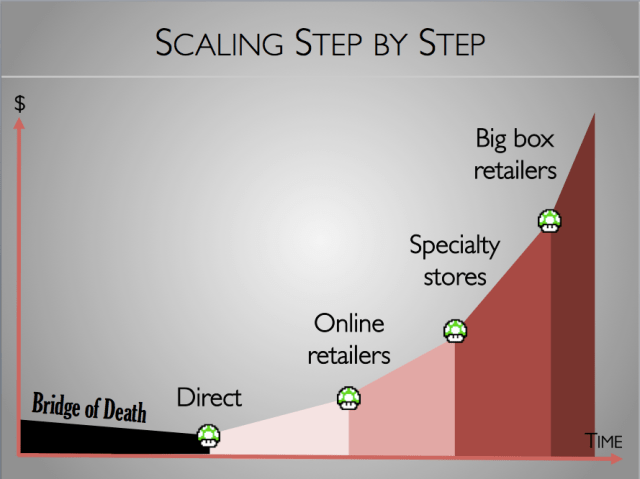

According to Charles Huang, co-founder of Red Octane, creators of the Guitar Hero franchise and of the gaming hardware startup Green Throttle: “Startups should know their return and defect rates before they try to scale. They can learn this through online sales or small boutique store sales. Maybe the second version is when the scaling should happen.”

So the advice is to learn about retail by doing it first on a small scale. This will give you enough time to learn the ropes, maybe until you get the second version of your product ready.

As Marc Barros, co-creator of the Moment mobile lens (currently on Kickstarter) and founder of Contour Cameras says: “Retail is not a sprint but a long slow build, so take one step at a time.”

Possible steps along the way are: direct sales online, specialty retailers (online and offline), Amazon and other large online retailers, then big box retailers. You need to understand the hidden costs of servicing each of them. In the case of offline retailers, it includes a laundry list of expenses related to in-store marketing, demo products, sales events and more.

The key points to remember are: keep demand higher than distribution, remember that your customers are your best investors, take one step at a time, and keep cash flow healthy.

If you can do that, you might become the next Nest, Square, GoPro or Xiaomi, or a flourishing hardware SME!

Cyril Ebersweiler is the founder of the hardware startup accelerator HAXLR8R (apply here) and Partner at SOS Ventures. Benjamin Joffe is an expert on startup ecosystems, angel investor and Advisor at HAXLR8R. Both spent over a decade in China and Japan and invest in startups around the world. This is the third part of a series on Lean Hardware.