I have a confession to make: despite having reviewed a few e-readers, and having written dozens of articles about them, I’ve never really used one. I mean, I’ve used them enough to know a good one from a bad one, to understand the features, and to do a proper evaluation — but I’ve never made one part of my life, the way one makes a mobile phone or laptop part of one’s life. In that way I haven’t really used an e-reader. Until just recently.

As a book lover, I view e-readers as interlopers; as a practical person, I acknowledge them as inevitable. But in both cases, I have come to view them as a deeply unsatisfying reading experience. They fall short of paper in meaningful ways, and objecting to them should not be considered technophobic.

The future of e-books is bright, but as far as I’m concerned, right now we’re still in the dark age — though that isn’t to say the stone age.

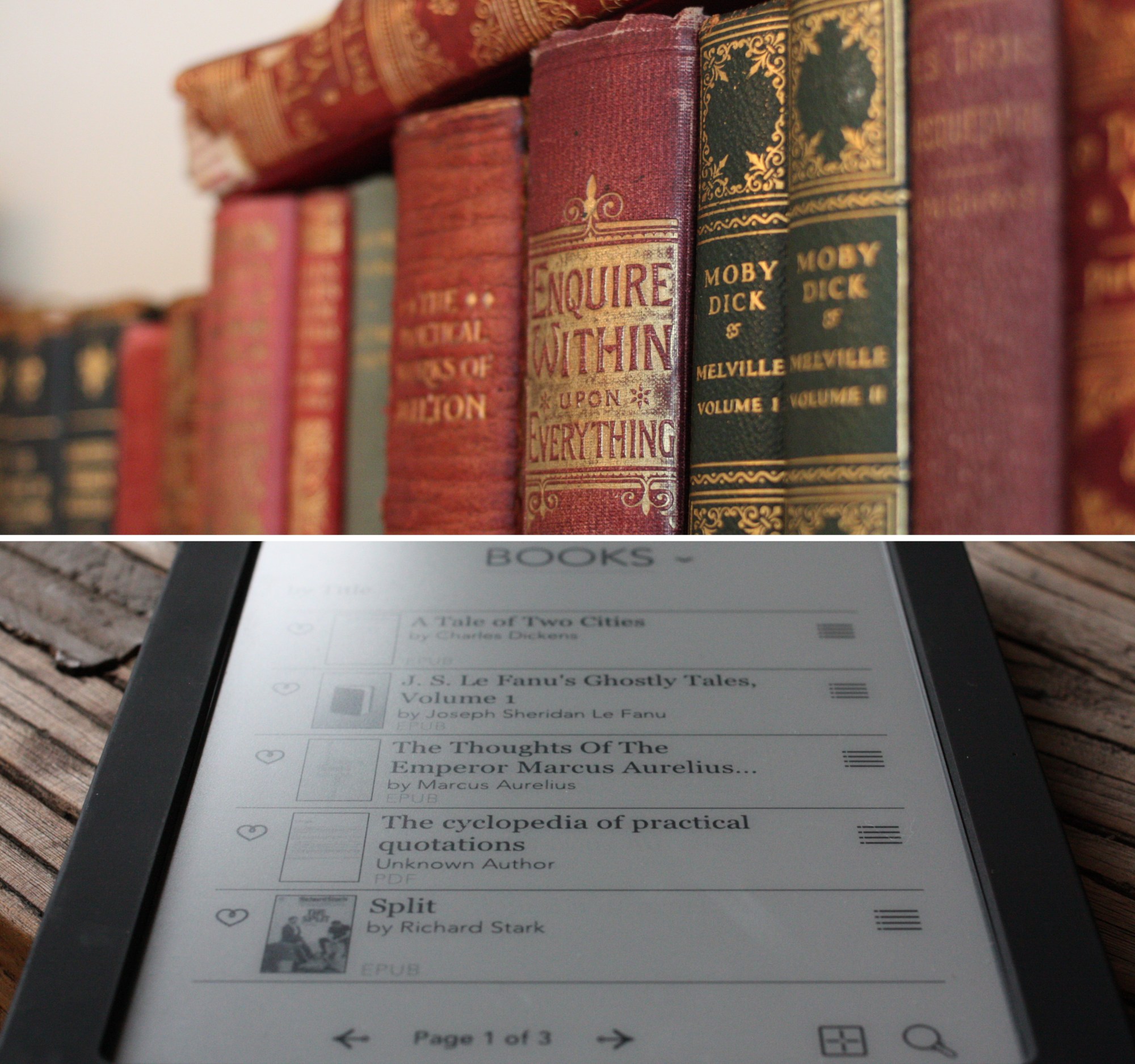

The core experience of the new Kindle, Nook, and Kobo (pictured) is practically the same. Sure, there are aesthetic differences and the selection is different, but when you’re doing what the devices are intended to do — reading a book, page by page — they are nearly identical.

Now I expect the PR departments have already started composing a new email with their talking points about how their device is the best, but let’s be realistic. These guys are using almost exactly the same parts (the most important bit, the screen, is the same in all three) and if you took the logos off the devices, few people would be able to tell you which is which or express a strong preference.

I don’t say this to denigrate the devices. This generation of e-readers is the most user-friendly and practical by far. But aside from the change to a touchscreen, e-readers have barely advanced from the day they were first introduced. So when I say I prefer paper, that’s not sentimentality. Paper really is just better.

No, I’m not putting you on or trying to play the devil’s advocate. But I’m willing to make a few concessions first. Obviously e-readers are better in a few ways: the wireless in the Kindle which allows you to get books almost wherever you are, for instance. And you can certainly keep more books on one device than you can keep in your carry-on. But that’s pretty much where the benefits end, isn’t it?

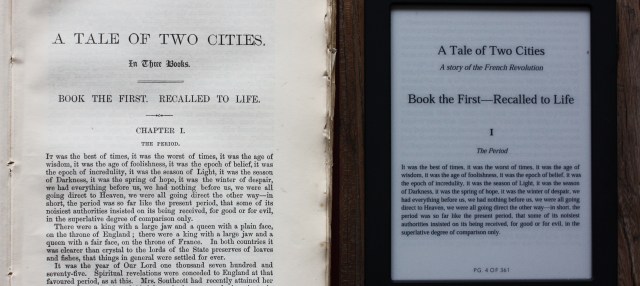

The screens aren’t actually that good. You can admit it, it’s okay. Even the newest ones. They’re rather grey, and the text doesn’t really look that good, does it? They’re a bit small, too. Don’t you feel it’s a bit limiting? You can’t replace a newspaper with this thing, and images look pretty bad. That blinking thing when it refreshes itself is annoying, finding a particular chapter or passage can be a pain, and lending or borrowing books isn’t as straightforward as it could be.

Am I just being an entitled consumer? A bit, yes. But there’s a good reason for my (mild and proportionate) frustration. The makers of e-readers have made a conscious choice over the last two years or so: provide the same product at a lower price, not a better product at the same price. It’s not that I have a problem with this. I wrote two years ago that this was the end game for the current players. That’s only an issue if, like in my case, the initial devices held no interest. For many, the race to the bottom was a good thing, making the basic e-reading experience possible for an extremely low price (and getting lower year by year). This is already having serious effects on the publishing and education ecosystems.

But what you see is also the inevitable result of companies relying on a dwindling pool of OEMs capable of manufacturing parts in the millions. The leading devices all use the same third-generation E-Ink display; few people would notice differences between the way they handle text, or care either way. As I mentioned, there are differences in the interface outside of books, and in how you search and buy, that sort of thing, but the purpose of these devices is to display e-books, and they all do it without appreciable differences.

Now, when their products are the same, companies compete on bullshit. We saw this in the 90s when every Compaq, HP, Dell, and Gateway PC was using the same pieces, and we see it today with TV makers who all have the same fundamental features and have to invent new numbers to increment at every CES. Markets at this stage are ripe to be broken into, as Apple is fond of doing. This point is when it often steps into the picture. I don’t mean to imply Apple will enter the e-reader wars (in fact, the iPad is their entry in a way), but someone is going to have to change the game. Selling a commodity, which is what e-readers have become, is a dangerous business in tech, because commodities tend to devalue rather quickly.

What needs to happen? A superior product, that’s all. E-readers can’t remain dumb, paperback-sized, text display gadgets forever. If they’re going to replace books, and paper, they need to learn a few more tricks.

It’ll take some time; no one wants to obsolete their own product, and these readers are setting up what is potentially a very profitable ecosystem. But at the same time, if they don’t do it, someone else might. Leave your lunch out too long and someone might just eat it for you. So you better believe that the big guys are planning real replacements for the e-reader of today, and are on the lookout for any sign that they might get beaten to the punch.

What will the new features be? Well, for example, Bridgestone has produced a screen that appears to beat E-Ink at every level. And half the electronic companies out there are hard at work on flexible OLED or bistable displays. Sony is testing the waters with a foldable tablet, and Readius has been flogging their flexible device for a while now. E Ink, conscious that they’ll have to make serious advances in order to keep their position as head bistable display honcho, is making screens that can be crumpled or attached to cloth. Color e-paper is shipping right now, though it’s not particularly good. Don’t expect the e-readers of tomorrow to be the same static window on text that they are today.

The screen quality, too, is going to have to improve. In both resolution and contrast, e-readers need to approach print on paper, or they will forever be understood as being a sub-par option, grey and indistinct. More comfortable to read on than LCDs, sure, but for how long? The advantage of the reflective display will eventually be outweighed by other factors if they don’t start moving.

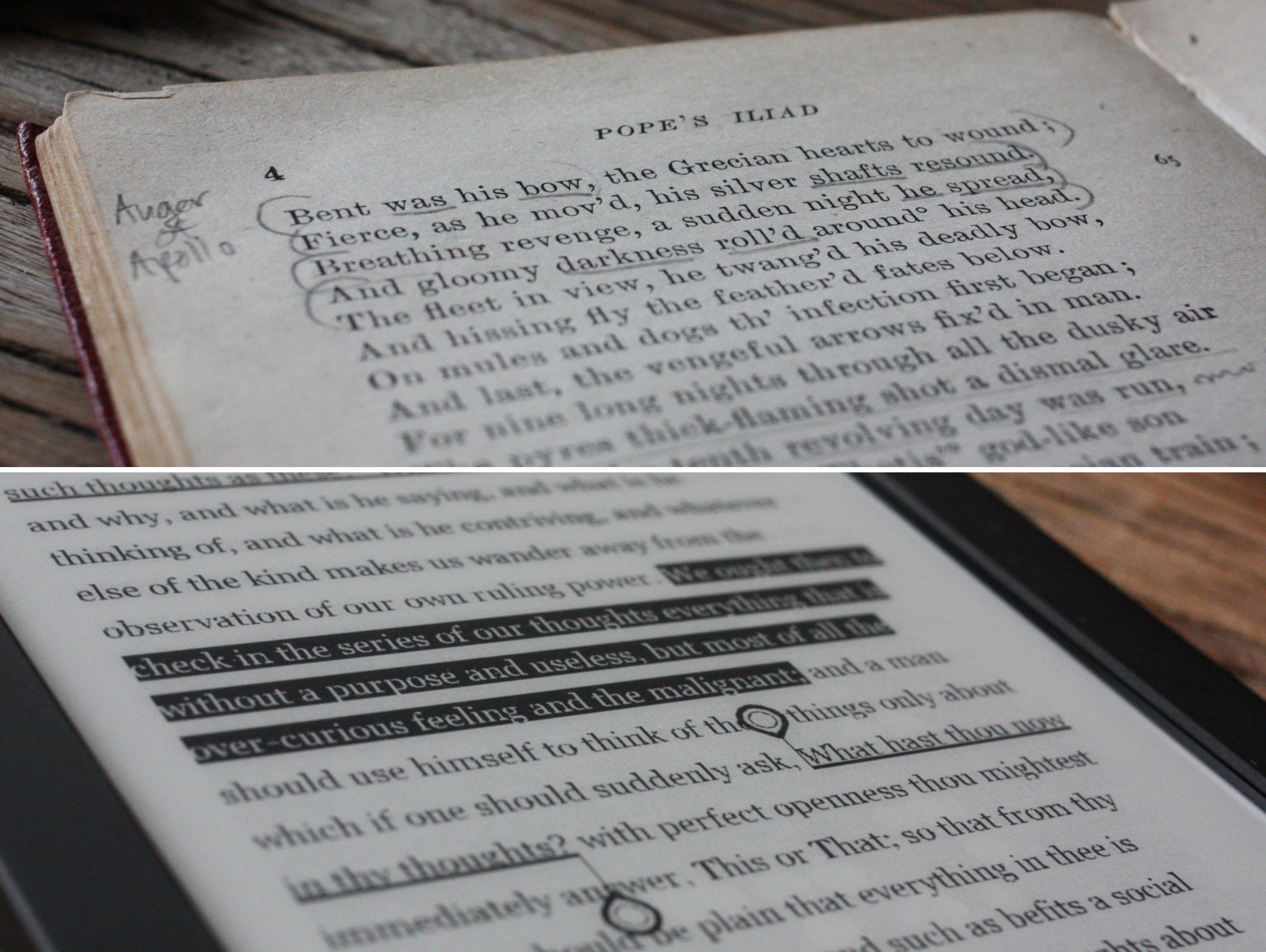

And we’ll want to write on them, too. The Noteslate device, unfortunately totally fictional (but apparently now in the works), awakened a sleeping giant of gadget envy on the net. Who wouldn’t want one of those things? Yet none of the major e-reading devices are even attempting it.

What else? Social and collaborative features, no doubt, like those just beginning to be promoted; more portability and ruggedness; features to enable reading by the blind, like quality real-time text-to-speech and tactile displays; richer formatting and rendering; self-illuminating screens or text; adjustable page tint; to say all, anything you can imagine might improve the reading experience, and probably a few things you haven’t imagined yet.

These fantasy devices don’t have to beat paper at everything — after all, they’ll never beat it on battery life — it’s just a little disappointing in how few ways they better their venerable competitor. And note that the e-reader should be considered distinct from the tablet (which, though more versatile, shares many shortcomings) as a device aimed specifically at consuming and storing text, and mostly black and white text at that. I suspect that factor will remain important for years to come.

Now, it’s not as if e-reader makers have been standing still all this time. Their devices are lighter, brighter, and faster, and making the screens touchable was a good move. But the problem is that after all these improvements, e-readers’ advantages over books still aren’t very significant. If you read one or two books at a time, and not big ones, the advantage is almost nil. E-readers should be way better than books! The possibility is there; the technology is there; the demand is there. There are dozens of things we would like to be able to do with our literature, our journals, our newspapers, that are inconvenient or impossible with existing form factors (paper, tablet, PC, or other). E-readers have a world to expand into, yet they are exploring it at a snail’s pace.

Why whine about this? Think back on the last ten years. How many tablets and MIDs do you spy with your little Internet eye? Dozens, most of them failures or niche products. Because, really, they simply weren’t good enough. E-readers have caught on to some extent, more so than the early tablets and MIDs certainly, but I would suggest that this is because of a pent-up demand for a device like this and not because of any particular fitness on its part. At the moment, they’re still quite crude, really — and we only tolerate their crudeness because right now convenience is valued over utility.

No one would blame you for not buying a Palm Pilot or Newton or early MID back in the day, because although they did have a purpose, they were, even at the time, clearly not mature products. E-readers aren’t mature either; don’t be fooled by the homogeneity of today’s options. They’re like that because of the decision they made, to drop prices instead of change the product. Just because they look alike and act alike doesn’t mean they are mature, the way PCs became mature in the late 90s.

These early devices ape semi-convincingly the experience of reading a book. Is that the end game? No. Should you expect something better? Yes. Should that stop you from buying one right now? Maybe.

For me, buying the most advanced e-reader today involves too many compromises in quality. The ways in which I read and interact with my books are simply incompatible with e-readers as they exist today. So I don’t buy, though in five years their successors will have me reaching for my wallet. It’s like seeing Microsoft showing off a tablet in the early 2000s. Did I want a tablet? Sure, ever since I first saw one — probably in Star Trek. But I didn’t try to buy that one, because it’s okay to say that something isn’t good enough for you. That’s the prerogative of the consumer. I don’t want a Kindle – I want what the Kindle will become, just as I wanted what the Treo and Newton would become. There’s no shame, and maybe even a little dignity, in waiting.

I love books. I love reading. And I love technology. But I can’t bring myself to even like today’s e-readers, except as promising indicators of things to come. For now, between paper and plastic, there’s no contest.