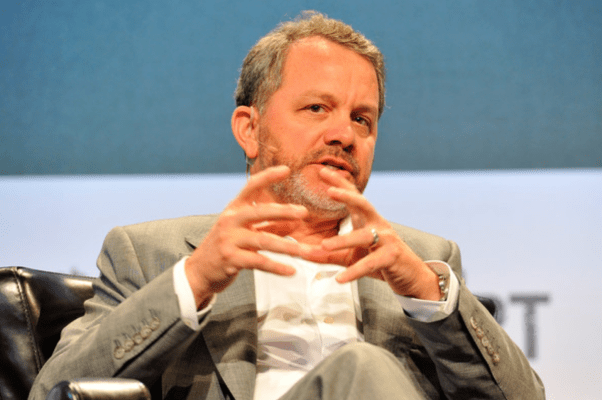

Bill McGlashan, who built his career as a top investor at the private equity firm TPG, has been put on “indefinite administrative leave, effective immediately,” says the firm after McGlashan was caught up in what the Justice Department said today is the largest college admissions scandal it has ever prosecuted.

McGlashan is among 49 others accused of participating in a bribery ring involving parents, admissions counselors, and athletic coaches at Yale, Wake Forest, and the University of Southern California (USC), among other institutions, in an effort to secure spots for their children at the schools.

“As a result of the charges of personal misconduct” against McGlashan, said the firm just now, Jim Coulter, Co-CEO of TPG, will be “interim managing partner” of the parts of TPG that McGlashan oversees, including TPG Growth and The Rise Fund.

“Mr. Coulter will, in partnership with the organization’s executive team, lead all investment work for both going forward,” according to a statement sent us by the firm.

McGlashan, who joined the private equity giant TPG in 2003, first to rethink and lead its earlier-stage strategy and, in more recent years, to lead its social impact strategy under the Rise Fund brand, is one of 33 parents being accused of trying to buy their kids’ admission. Others include actresses Felicity Huffman and Lori Loughlin.

For McGlashan especially, whose job is ostensibly to make a measurable, beneficial social or environmental impact, the charges are particularly damning, highlighting as they do how wealthy families sometimes use their financial muscle in socially unjust ways — in this case, paying to secure spots at colleges and depriving deserving students of admission in the process.

Indeed, TPG seemingly had little choice but separating from McGlashan, at least for now. In making its case against McGlashan and the others, the Justice Department has laid bare each party’s alleged wrongdoings with painstaking specificity.

For his part, McGlashan has been charged with both participating in a college entrance exam cheating scheme and recruitment scheme, including by trying to bribe the senior athletic director at USC, and by paying test center administrators willing to accept bribes to give his oldest son more time to take a college entrance exam than is usually allotted students — and in a special test center where his answers would be corrected after he had completed the test (unbeknownst to him).

McGlashan also allegedly signed-off on plans to doctor a photo that would make McGlashan’s son look like a football recruit and, as McGlashan was told, thus more desirable to the specialty program in arts, technology and business at USC that his son hoped to attend.

This wasn’t all theoretical. According to the Justice Department, after McGlashan’s son took the test in Florida and after the proctor corrected his answers to produce a score of 34 out of 36, it was provided as part of his application to Northeastern University in Boston.

Worse for McGlashan, according to the Justice Department’s complaint, McGlashan discussed with these outside parties repeating the ACT cheating scheme for his two younger children, and parts of these conversations were recorded via a court-authorized wiretap. Here’s just one outtake of many with a participant turned cooperating witness (identified as CW-1):

McGLASHAN: One other, just family question, with [my younger son] now entering his sophomore year, and sort of, the process is beginning, we have him on time and a half. I told [my spouse] yesterday, and [my daughter] by the way, who is the, who I think is the one who needs the most time, has no extra time currently. And [my spouse] is talking to the doctor that assessed them, to get her to ask, to request time for [my daughter]. I told her she should be requesting double time for all of them.

CW-1: 100% multiple days. No matter what, multiple days. So, even if it’s 50%, time and a half, multiple days.

During the call, McGlashan also tries to ensure that his son won’t know that his scores have been tampered with, or the degree to which McGlashan has inserted himself into the process.

McGLASHAN: Now does he, here’s the only question, does he know? Is there a way to do it in a way that he doesn’t know that happened?

CW-1: Oh yeah. Oh he–

McGLASHAN: Great.

CW-1: What he would know is, that I’m going to take his stuff, and I’m going to get him some help, okay?

McGLASHAN: So that, that he would have no issue with. You lobbying for him. You helping use your network. No issue.

CW-1: That letter, that letter comes to you.

McGLASHAN: Yup.

CW-1: So, my families want to know this is done.

McGLASHAN: Yup.

Somewhat unbelievably, the cooperating witness goes on to explain that to take advantage of a “side door” that could further strengthen the odds that McGlashan’s son will be accepted at USC, he will need to create a fake athletic profile for McGlashan’s son, which he says he has done “a million times” for other families. As remarkably, after McGlashan tells him that his family has images of the teenager playing lacrosse and is told by the cooperating witness that USC doesn’t have a lacrosse team, McGlashan is then told that a picture of his son “doing something” – – anything vaguely sporty, in other words – – will “be fine.”

CW-1: I have to do a profile for him in a sport, which is fine, I’ll create it. You know, I just need him– I’ll pick a sport and we’ll do a picture of him, or he can, we’ll put his face on the picture whatever. Just so that he plays whatever. I’ve already done that a million times. So–

McGLASHAN: Well, we have images of him in lacrosse. I don’t know if that matters.

CW-1: They don’t have a lacrosse team. But as long as I can see him doing something, that would be fine.

McGLASHAN: Yeah.

CW-1: And then what happens is, then what you have to do, because this would be a specialty program, is that you have to then talk to the department and say, “Hey listen, can you take him in the department? We’ve gotten him accepted into the university.”

McGLASHAN: Yup. Well I can handle, I think I, I mean, I’ll know after this lunch. I think I can handle them at Iovine and Young.

CW-1: Right.

McGLASHAN: Yeah. Which is where he really wants to go.

CW-1: Right. So you’re saying, “Hey listen, I think I can get him into this school.”

McGLASHAN: Yup.

CW-1: Now, now, can you, ’cause they’re going to come to you and say, this is a selective program, would you want this kid? And he’s quote an “athlete” who’s coming to you. In fact, would you take him? And the department says yes.

Again, McGlashan worries about his son learning of his involvement and wonders if he should try USC’s board instead, where he knows “half” the directors. He’s advised against reaching out to his contacts there, however.

McGLASHAN: Now, would he see that, ’cause that, he’s going to be fairly well seen at the school, because half the board knows me, and I’m going to be sort of 64 calling in and asking people to help, you know [Board Member 1] and [Board Member 2], and all those guys?

CW-1: But, so– what I would suggest is, have you called them? Any of them yet?

McGLASHAN: No.

CW-1: Good, don’t.

McGLASHAN: Okay.

CW-1: Because you don’t need, because when this, the way this, the quieter it, the quieter this is, the better it is, so people don’t say, “Well, okay, this guy, why are all these people calling us? The kid’s already been accepted. He’s coming here as an athlete. He’s already in.” What you just want is, the person you’re meeting with on Friday to say, you know, what we want [is] this kid.

McGLASHAN: So he doesn’t have to know how he got in. Is that the case?

CW-1: What I would say to him, if you want to have that discussion now with [your son] there, that we have friends in athletics, they are going to help us, because [he] is an athlete, and they’re going to help us. From the–

McGLASHAN: But I can’t say that in front of [my son], ’cause he knows he’s not.

CW-1: No, no, right.

McGLASHAN: Yeah.

CW-1: And just say, you know what, we’re going to get, we’re going to get some, we’re going to get people to help us.

McGLASHAN: Why wouldn’t, why wouldn’t I say, “Look, leave it to me to worry about getting him in, ’cause I have a lot of friends involved in the school.”

CW-1: Perfect, perfect.

Ultimately, McGlashan shelled out more than $250,000 in the scheme. Unfortunately for everyone involved, the decision to get involved in his son’s college admissions process may wind up costing much more than that.