Late last year Uber announced that it was pulling out of several major German markets, the latest in a series of challenges as it attempts to expand internationally.

Is this just a minor misstep — or a harbinger of more serious troubles ahead?

Uber — along with competitors like Lyft, and sharing-economy cousins such as Airbnb — is arguably performing a valuable service by forcing tired old industries to innovate and to improve the quality of their offerings.

Undoubtedly, this creates a sense of purpose at such companies that can translate into urgency in the minds of executives and investors who believe in the righteousness of their disruptive mission.

At the same time, the greatest imperative for Uber and its rivals is not market reform, but return on investment. And in that context, the urgency to gain market share has led Uber to make unforced errors as it expands internationally.

Uber has run into obstacles in several international markets. It has tangled with law enforcement in France, where two top Uber executives have been arrested, and in the Netherlands, where police raided the company offices. In multiple markets, proposals have been mooted — with mixed success — that could impair Uber’s ability to freely operate.

In part these difficulties are the expected consequences of introducing new business processes into a global marketplace still built to favor older models. In this respect, Uber’s challenge internationally is not much different from its challenge in the US, where it has had to win approval sometimes city by city.

But as Uber is learning, international can be different. Approaches that work in the US may not work when applied abroad. Underlying cultural and philosophical assumptions may prompt a different local reaction to new market entrants even if some of the industry dynamics seem the same.

There are things the company could do differently.

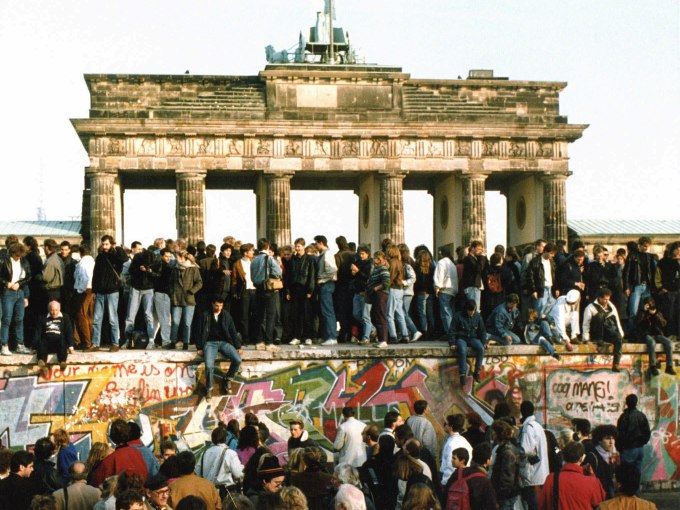

Don’t Rush Headlong Into a Brick Wall

Uber has justified its focus on rapid international expansion as a blocking move against the likely emergence of local competitors — or “clones,” as one Uber investor described them in a Reuters article last year. If Uber doesn’t expand as fast as possible, goes the logic, foreign copycats will emerge and eat Uber’s lunch.

But in reality, the challenge for Uber has been posed not by clones but by homegrown competitors who have leveraged their better knowledge of local market dynamics to build successful businesses. These businesses may share some similarities with the Uber model, but they differentiate themselves by working in accordance with local regulations.

MyTaxi, founded in 2009, works with licensed taxi drivers and now has more than 22,000 drivers in Germany — and the same number again in other European markets. Taxi.eu, founded in Berlin, has 160,000 drivers in 12 European markets signed up to take bookings via its smartphone app.

Local competitors sensed that Uber was likely to hit a brick wall with its aggressive approach. Ironically, Uber might have enjoyed greater success, faster, if it had taken a more patient, collaborative approach — working with licensed incumbents rather than competing directly against them.

Challenge Authority Respectfully

Germans love speed, but they don’t love recklessness: the reason one can drive fast on the autobahn is because one can be confident that other drivers will follow the rules of the road.

American companies, by contrast, are accustomed to a culture built on rejecting rules and deregulation has been gospel to the American political and economic mainstream since the 80s.

I remember a conversation I had in 1998 with a journalist in Paris. Newly arrived from Silicon Valley, in my senior role working for a big American internet company, I declared with certainty that the French wouldn’t want regulators to decide what’s best for them in the digital realm. The reporter replied, quite patiently, “In France we tend to think it’s a good thing when the government seeks to protect citizens’ interests.”

In European markets, succeeding within the rules is a badge of honor. Breaking the rules, even in pursuit of a seemingly worthy goal such as improving market efficiency or consumer choice, can be seen as offensive and not something to necessarily be applauded.

Instead of taking an adversarial approach, market entrants such as Uber might consider approaching authorities and incumbent players and saying, “Here’s what we’ve learned. How can we work with you to implement these learnings in your market, for the benefit of your local businesses and consumers?”

By the time Uber tried a more cooperative approach in Germany — reaching out to licensed taxi operators — it was too late. Uber had alienated the operators, regulators and many consumers; had empowered local rivals and could not gain sufficient cooperation to maintain its presence in German cities.

Form A Big Tent

Uber may feel that it can afford to do battle, given its enormous funding war chest. It can hire lobbyists and litigators in multiple markets and persist until it succeeds in beating back legal challenges and seeing regulations made more friendly.

But let’s say Uber succeeds in becoming a wild success story across Europe. After consolidating its gains into a position of dominance, Uber could potentially look forward to costly antitrust challenges similar to those that bedeviled Microsoft in the past and which are keeping Google currently occupied. Although antitrust enforcement has largely been abandoned in the US, Europeans still take it very seriously.

In any case, local rivals who are already adept at playing by the rules will adapt quickly to new rules if it suits them to do so. If Uber succeeds in getting regulations changed, those changes will apply equally to everyone else. Locals can sit back and let Uber fund these costly battles — and then those locals can adapt their processes to incorporate any resulting new developments.

Rather than taking an adversarial approach, a “big tent” approach leaves room to share gains with others, to win the support of consumers and to grow as a member of the community. It deflects criticism and protects against charges of unfairness. It turns companies into partners rather than adversaries.

Uber’s retrenchment in Germany can’t be looked at as a permanent retreat, especially given the company’s considerable resources. They may pull back for a while, and then try again later. They can afford to.

But it’s dangerous to have too many missteps on the international front, especially when massive valuations are tied to expectations for substantial growth, and such substantial growth can only be achieved on a global basis.

No company with global ambitions can afford to develop a perception that it is insensitive, arrogant — the proverbial ugly American. Uber may very well win out through brute force. But it wouldn’t hurt to learn the art of diplomacy.