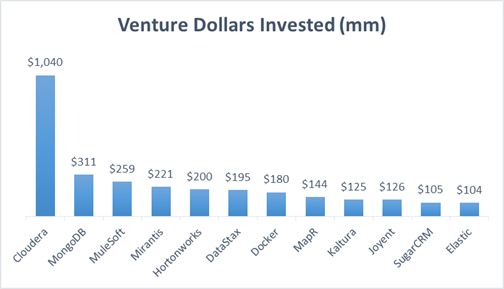

It’s no secret that open-source technology — once the province of radicals, hippies and granola eaters — has gone mainstream. According to industry estimates, more than 180 young companies that give away their software raised roughly $3.2 billion in financing from 2011 to 2014.

Even major enterprise-IT vendors are relying on open-source for critical business functions today. It’s a big turnaround from the days when former Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer famously called the open-source Linux operating system “a cancer” (and obviously a threat to Windows).

Despite the growing popularity of open-source software, though, many open-source companies are not financially healthy. Just like eyeballs didn’t translate into actual online purchases during the first dot-com era in the late 1990s, millions of free-software downloads do not always lead to sustainable revenue streams.

Make no mistake, open-source software is a brilliant delivery model to drive user adoption, and it’s poised to drive increasing market value in the coming years. But it’s not a business model on its own.

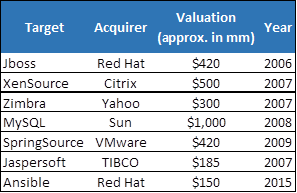

Source: Publicly available data

Just how challenging is it to build a big, profitable open-source business? Consider this: Besides the ongoing success of Red Hat — the company now boasts a $14 billion valuation, built over 20 years — and MySQL’s acquisition by Sun for $1 billion in 2008, there are few other landmark exits in the history of open source.

But success, for entrepreneurs and investors alike, is possible. Based on our experience working with open-source names, including Mirantis*, Cloudera*, MongoDB* and others, we have isolated some key lessons for entrepreneurs to consider as they build open-source communities and sustainable businesses in parallel; the two don’t have to be mutually exclusive.

Think about a business model from day one

This seems obvious, but you’d be surprised how often open-source entrepreneurs think of their business model only after their free-software downloads are off the charts. In contrast, our experience suggests that some of the best open-source companies had a clear idea of how they were going to make money from their early days.

Companies often do this by selling enterprise versions of open-source projects with extra security and management features. These are designed to appeal to the large enterprises that are big IT spenders. Another option is to offer a premium SaaS service, essentially a pay-as-you-go model. While delivering a reliable service can be difficult — namely, packaging many open-source components together into one compelling, cloud-based offering — SaaS can be another route to revenue.

Red Hat is a good example of a company that thought about monetization from the get-go. Early on, when the company was shifting from shipping Linux CDs in textbooks toward selling to big enterprises, executives drew a clear delineation between the company’s free Fedora user community and the more sophisticated Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) product. They recognized that their target buyers — CIOs and operations executives — valued stability over features, and these execs wanted an enterprise-grade, paid product supporting their core Linux applications.

Some of the best open-source companies had a clear idea of how they were going to make money from their early days.

So while Red Hat maintained a vibrant open-source community around Fedora, updating it with new features and releases every six months, the company marketed enterprise-grade security and optimization on standard Intel hardware to people using the paid enterprise product. This allowed Red Hat to build a recurring revenue stream of more than $1 billion from enterprise customers; it also, more broadly, helped Linux become the most widely adopted server operating system.

Another forward-thinking open-source company, Cloudera, comes from the big-data world, where several companies are trying to commercialize the open-source project called Hadoop. Like Red Hat, Cloudera has reserved some important enterprise features — security, performance and business analytics — for its higher-end product, called Enterprise Data Hub. Meanwhile, big-data competitor Hortonworks is trying to make money from paid product support, which may be a more difficult model.

The Apache software foundation, whose open-source server software burst onto the tech scene in the 1990s, led to many vendors trying a similar strategy — essentially, selling customers support as a sort of insurance policy on their deployments, which some users considered risky because they were based on open-source technology. Over time, though, many customers got comfortable with the products and didn’t need the support — demonstrating that this was not a long-term strategy for monetization.

Source: Publicly available data

Pick a licensing model aligned with your monetization strategy

Open-source licenses determine exactly who owns modified versions of your open-source product, and can have big implications for your business. Some licenses allow anyone to create closed-source derivative works that build on the original product, while others reserve that right only for the owners of the original product. This is a big deal when you’re trying to figure out how to add features to your product that people will purchase.

Keep in mind that even open-source software is always owned by someone, usually either a for-profit company or a non-profit foundation (kumbaya only goes so far). Licenses range from permissive (Apache) to restrictive (General Public License, or GPL, variants, with Affero GPL the most restrictive), and everything in between.

There are 71 different flavors, to be exact, all listed on opensource.org. More permissive licenses make it easier to build large ecosystems. If any open-source project can incorporate yours, you can get a tailwind by being included in, or connected to, other successful projects. Looser licenses also may make it easier to solicit contributions to the product, and they make users more comfortable that the project is less dependent on a small startup.

Keep in mind that even open-source software is always owned by someone.

At the same time, allowing anyone to add enterprise features to your product makes it harder to create sustained differentiation, build revenue and avoid fragmentation. A case in point is the popular OpenStack project for cloud infrastructure, governed by the OpenStack Foundation. Early buy-in from tech giants like Intel, Red Hat, H-P, Dell, Juniper and others was critical to early support from large users like PayPal, Walmart and Symantec, who knew their core infrastructure foundation was supported by the broader community and large hardware companies.

However, OpenStack recently has been criticized for moving in multiple directions, driven by the various hardware players who all have competing business and strategic agendas and, now, products that may not work well with each other. This has led to the emergence of two vendors, Red Hat and Mirantis*, who promise to be the “Switzerland” of the ecosystem and work with everyone. It seems a compelling business case, given the problems this permissive license has created.

MongoDB, by contrast, has consistently followed the stricter AGPL license model. Despite using a strict license, MongoDB’s software has become very popular. This happened mostly because the company offered a compelling product: a simple, flexible-document database that many developers found much easier to use than older relational databases. That product trumped the restrictive license.

Within two years, MongoDB had amassed millions of downloads; it has 10 million today. For open-source entrepreneurs who believe their product can gain wide adoption without having to piggyback on the success of other open-source projects, a more restrictive license may be better in the longer run. But if you go that route, be prepared to invest heavily in building community in the early days.

Ancillary services and “hand holding” may be necessary, but don’t get hooked on them for revenue

Open-source software has disrupted some of the most important technologies in enterprise infrastructure: think MongoDB and Cassandra taking on legacy Oracle databases, OpenStack and Docker threatening virtualization giant VMware and Linux displacing Solaris and Windows Server software. What helped these open-source underdogs grow was real-world successes — not, as some entrepreneurs think, pricey consulting services to augment deployments.

In the early days of open-source adoption, of course, some professional services and “hand holding” may be necessary to get open-source systems off the ground, especially when customers are dealing with integrating legacy software. Indeed, some of the earliest Hadoop, OpenStack and Cloud Foundry deployments needed consulting services to make key customers successful.

Focus on building your recurring revenue from subscriptions.

But don’t try to build your business on services revenue. It carries a lower gross profit margin than other revenue streams — perhaps 20-30 percent, as opposed to 90 percent for product-related revenue — and it’s not generally repeatable. Ultimately, if you’re successful, you’ll have millions of users, but you’ll only be able to tap perhaps a few hundred of them for services revenue.

Plus, if you chase services revenue too aggressively you could wind up competing with services partners (e.g., Accenture, IBM) that could help bring you new users. Our advice: Focus on building your recurring revenue from subscriptions, which should be your high-margin core product. Build your services organization to support customer success and partner success, not to drive revenue. What’s more, we would even support aggressively cannibalizing your services business by making your product easier to use and your partners more capable, so that they can take over running it themselves in the longer term.

Ongoing customer satisfaction trumps upfront sales

Sales cycles in open source are very different from those in traditional, enterprise software. With regular, enterprise software, it’s often hard to convince customers to use the technology; on top of that, they have to pay for it. In open source, that decision process is often bifurcated, happening in two separate steps. Convincing people to use your software is often much easier, because the product may be initially free. But then you face a separate task, later, to convince them to pay.

This shift can be disorienting for those who are used to traditional enterprise-software sales and marketing. Reps can spend lots of time trying to convince someone to use your software — and succeeding — but then not wind up with any revenue for their effort. In the early days of your company, that might be okay, because you’re also trying to build your user base, which could turn into revenue later.

Clearly, making money from free software is possible.

But even after you grow, and start racking up sales, you need to become very disciplined about getting your sales team to focus on ongoing customer satisfaction, because happy customers buy more, and buy products with higher ASPs (average selling prices). This, in turn, helps subsidize your ongoing R&D. Overall, this is quite different than most enterprise-sales models, which focus on making the sale and moving on to the next prospect.

Salespeople need to be measured on the subscription revenue they are bringing in, while a separate team focused on community should nurture adoption growth. This may mean hiring a different type of salesperson — someone who may not be from the high-pressure Oracle mold, for instance, though those folks can still succeed with the right type of training.

At MongoDB, we had a very successful salesperson who had previously started a sports-uniform business and another business to clean roof gutters. He may not have had a lot of software experience, but he was fanatical about customer satisfaction.

Getting past the open-source revenue conundrum

Clearly, making money from free software is possible, and there are different paths to doing it successfully. But focusing on monetization and licensing from the beginning, and building the right type of services model and sales team, are key tactics for doing it right. We now have plenty of corporate case studies from the last 20 years that demonstrate that you can indeed build a profitable, open-source company that is also very popular with users.

In other words, you can have your granola and eat it, too.

*Denotes an investment by Mr. Thakker when he was at Intel Capital.