I became interested in Uber after reading a news story in June 2014, which reported the company was being valued at $17 billion in its latest venture capital round.

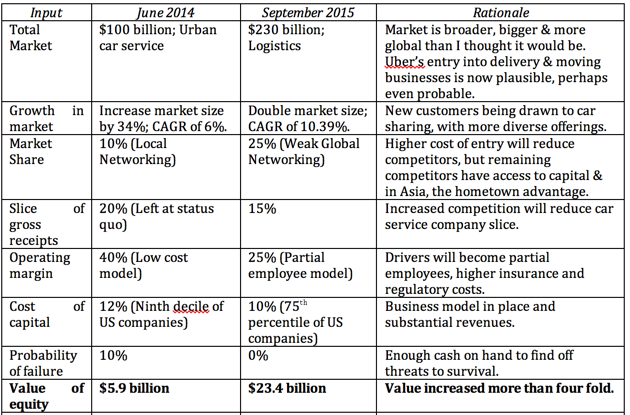

I posted my first valuation of Uber in June 2014, viewing it as an urban car service, with local (but not global) networking benefits. Assuming that it would increase the size of the urban car service market by about 40%, while preserving its low capital-investment business model, I valued Uber at just under $6 billion.

While some in the VC community were quick to dismiss the valuation, I will remain grateful to Bill Gurley for a post where he took me to task for having too narrow a vision of Uber’s business model.

In his counter narrative, he argued that Uber was not just urban (it could create inroads in suburbia), not just a car service (it was in logistics & transportation) and that it was working with other businesses to create global networking benefits.

Since Bill, as an early investor in Uber with access to its internal workings, clearly knew far more about the company than I did, I revalued Uber using his narrative and arrived at $54 billion as the value that reflected the narrative.

Then value investors took issue with the company’s valuation changing so dramatically from my assessment to his, and my response was that this was exactly what you should expect early in the life of a company, where there is room for widely divergent narratives, and values that reflect these divergences.

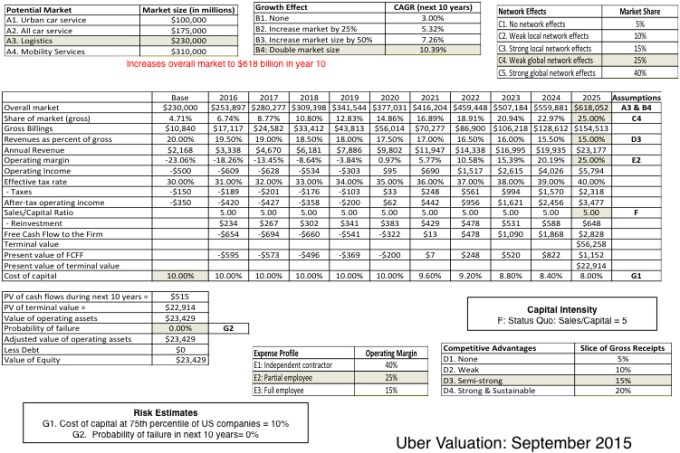

In December 2014, I tried to show this by creating a build-your-own-Uber valuation template, where I let readers choose Uber’s market (urban car service, all car service, logistics or mobility services).

Users could see the effect changing Uber’s business would have on its market size (from none to doubling it); the competitive advantages that would determine its cut of the ride receipts (from the existing 20% down to 5%); the networking benefits it would have (none, local, partially global, and global) and business model (from its current no capital intensity to higher capital investments); and derived values for Uber — ranging from less than $1 billion to close to $100 billion.

The News Keeps Coming..

Each week brings more Uber stories, with some containing good news for those who believe that the company is on a glide path to a $100 billion IPO, and some containing bad news, which evoke predictions of catastrophe from Uber doubters. For me, the test with each news story is to see how that story affects my narrative for Uber, and by extension, my estimate of its value. In keeping with this perspective, I broke the news stories down based upon narrative parts and valuation inputs.

The Total Market

The news on the car service market has been mostly positive, indicating that the market is much broader, growing faster and more globally than I thought it was, even a year ago.

- Not just urban and much bigger: While the car service application remains most popular in urban areas, it’s making inroads into exurbia and suburbia. A presentation to potential investors in the company put Uber’s gross billings for 2015 at $10.84 billion. These are unofficial and may have some hype built into them, but even if that number over estimates revenues by 20% or 25%, it represents a jump of 400% from 2014 levels.

- Drawing in new customers: This increase in the car service market comes from customers who would never have been in this market in the first place.

- With more diverse offerings: The ride sharing market is also no longer just a cab service, but instead has expanded to include alternatives that expand choices, reduce costs (car pooling services) or increase flexibility.

- And going global: The biggest stories on ride sharing came from markets outside of the U.S., as the ride sharing market exploded in regions like India and China. That should really come as no surprise since these countries offers the trifecta for ride sharing opportunities: large urban populations, with limited car ownership and bad mass transit systems.

The bad news on the car service market front has come mostly in the form of taxi driver protests, regulatory bans and operating restrictions.

Even that bad news, though, contains seeds of good news, since the status quo would not be trying so hard to stop the upstarts, if ride sharing was not working.

The attempts by taxi operators, regulators and politicians to stop the ride sharing services reek of desperation, and the markets seem to reflect that. Not only have the revenues collected by taxi cabs in New York city dropped significantly in the last year, but so has the price of NYC cab medallions, losing almost 40% of their value (roughly $5 billion in the aggregate) in the last two years.

In my December post, I noted the possibility that Uber could move into other businesses. The good news is that it has delivered on this promise, offering logistics services in Hong Kong and New York, and food delivery service in Los Angeles.

The bad news is that it has been slow going, partly because these are smaller businesses (than ride sharing) and partly because the competition is more organized. However, these new businesses have moved from just being possible to plausible, thus expanding the total market

Bottom line: The total market for Uber is bigger than the urban car service market that I visualized in June 2014, and will attract new customers, and expand in new markets (with Asia becoming the focus), and perhaps even in new businesses.

Networking & Competitive Advantages (Market Share And Revenue Sharing)

Ride sharing companies have increased the cost of entry into the market, with tactics such as paying large amounts to drivers as sweeteners to sign up. In the US, Uber and Lyft have become the biggest players, and some of the competitors from last year have either faded away or been unable to keep up with these two.

Outside the US, the good news for Uber is that it is not only in the mix almost everywhere in the world but that Lyft has, at least for the moment, decided to stay focused on the United States in its expansion choices.

The downside for the company has been in global markets. Especially in Asia, the competition has been intense, and Uber is fighting against domestic ride sharing companies that dominate these markets: Ola in India, Didi Kuaidi in China and Grabtaxi in South East Asia.

The dominance of domestic market players can be attributed to these companies being first movers and understanding local markets better, but some of it also reflects that the market is tilted (by local investors, regulation and politics) towards local players.

There is even talk that these competitors will band together to create a “not-Uber” network, and that story got backing two weeks ago when Didi Kuaidi and Lyft announced a formal partnership. All of these ride sharing companies are able to access capital at sky-high valuations, reducing the significant cash advantage that Uber had earlier in the process.

As competition picks up, one of the key numbers that will be under pressure is the share of the gross billing, currently set at 80% for the driver and 20% for the ride sharing business. In many US cities, Lyft is already offering drivers the opportunity to keep all of their earnings, if they drive more than 40 hours a week. While the threat of mutually assured destruction has kept both companies from directly challenging the 80/20 sharing rule, it is only a matter of time before that changes.

Bottom line: The ride sharing market is becoming competitive, but as costs of entry rise and the capital requirements become intense, it looks like this will be a market with fewer players with larger regional networking benefits and more capital.

Cost Structure

This is the area of most concern for Uber. Some of the pain has been from within the ride sharing business; as companies have taken to offering larger and larger up-front payments to drivers to get them to switch from competitors, pushing up that component of costs. Much of the cost pressure, though, has come from outside:

- Drivers as partial employees: Early in the summer, the California Labor Commission decided that Uber drivers were employees of the company, not independent contractors. Courts further affirmed the decision, ruling that Uber drivers could sue the company in a class action suit. Other jurisdictions are likely to follow suit. That drivers for ride sharing companies will be treated perhaps not as employees but as semi-employees, entitled to some (if not all) of the benefits of employees (leading to higher costs for ride sharing companies) is almost inevitable.

- The insurance blind spot will be filled: Ride sharing companies in their nascent years exploited the holes in auto insurance contracting, often just having to add supplemental insurance to the insurance that drivers already have. As regulators and insurance companies try to fix this gap, it’s very likely that drivers for ride sharing companies will soon have to buy more expensive insurance and that ride sharing companies will have to bear a portion of that cost.

- Fighting the empire is not cheap: Earlier in this post, I noted that the status quo (the taxi business and its regulators) was fighting back and that its cause was hopeless. However, the fight will still be expensive as the amount of money spent on lobbying and legal fees will increase, as new fronts open up.

The evidence that costs are running far ahead of revenues again comes from leaked documents from the ride sharing companies. This one, for instance, shows that Uber was a money loser last year and in this one, the contribution margins (the profits after covering just variable costs) by city not only reveal big differences across cities but are uniformly low (ranging from a high of 11.1% in Stockholm and Johannesburg to 3.5% in Seattle).

Bottom line: The costs of running a ride sharing business are high, and while some of these costs will drop, as business scales up, the operating margins are likely to be smaller than I anticipated just over a year ago.

Capital Intensity And Risk

The business model that I assumed for my initial Uber valuation relied on minimal capital requirements, since Uber neither owns the cars driven by its drivers, nor invests heavily in corporate offices or infrastructure.

That translated into a high capital turnover ratio, with a dollar in capital generating five dollars in additional revenues. While that basic business model has not changed, ride sharing companies are recognizing one of the downsides of this low capital intensity model is that it has increased competition on other fronts.

Thus, the high costs that Uber and Lyft are paying to sign up drivers can be viewed as a consequence of the business models that they have adopted, where drivers are free agents without contracts.

For the moment, there is no sign that any of the ride sharing companies is interested in altering the dynamics of this model, by either upping its investment in infrastructure or in the cars themselves, but this news story about Uber hiring away the robotics faculty at Carnegie Mellon may be suggestive of change to come.

Bottom line: Ride sharing companies will continue with the low capital intensity model, for the moment, but the search for a competitive edge may result in a more capital intense model, requiring more investment to deliver sustainable growth.

Management Culture

Though not a direct input into valuation, it is unquestionable that when investing in a young business, you should be aware of the management culture in that business. With Uber, the news stories about its management team and the responses to these stories reflect your prior opinions on the company. If you are predisposed to like the company, you will view it as confident in its attacks on new markets, aggressive in defending its turf and creative in its counter-attacks. If you don’t like the company, the very same actions will be viewed as indicative of the arrogance of the company, its challenging a status quo will signal its unwillingness to play by the rules and its counter attacks will be viewed as overkill.

Bottom line: There seems no reason to believe that Uber will become less aggressive in the future. The question of whether this will hurt them as they scale up remains unresolved.

Uber: An Updated Valuation

In summary, a great deal has changed since June 2014, partly because of real changes that have happened to the ride sharing market since then and partly because I had to fill in gaps in my ignorance about the market. In the table below, I compare my inputs on key numbers in June 2014 with my estimates in September 2015.

I was wrong about Uber’s value in June 2014, when my estimate of $6 billion was below the $17 billion assessment by venture capitalists then. Correcting for both my cramped vision and the changes that have occurred since June 2014, my estimated value today is $23.4 billion.

I know my estimated value lags the $51 billion value that VCs are attaching to the company today. This may very well be a reflection that my vision is still too cramped to capture Uber’s possible businesses, but it is what it is.

Fire away

At this point in this post, if you are in complete agreement with my Uber valuation, I have failed. I would rather that you fall into one of three groups: that you think my value is too high, that you feel it is too low or that you believe that I have no business even valuing Uber.

- If you think I have over estimated the value of Uber, it should not be because it is losing money, is trading at a high multiple of revenues or because your stable growth dividend discount model gives you too low a number.It should be because you think the regulatory roadblocks will make the ride sharing market smaller than I have forecast it to be, and that competition will be much more intense, reducing market share and operating margins.

- If you think that I have under estimated the value of Uber, don’t blame DCF models for being biased against growth companies.The fault has to be somewhere in my inputs, i.e., that I am not foreseeing other markets that Uber could enter, that its networking benefits are far stronger globally than I predict them to be (giving it a higher market share) or that the operating margins will bounce back to much healthier levels once they navigate their way through the growth phase.

- If your view is that I have no business valuing Uber, because I am not a tech person, that I am not a ride sharing expert in and/or that I have not made money as a VC, my responses are guilty as charged, you are right and without a doubt.I don’t have a tech background, don’t work on the right coast and know technology only as a user, but I don’t think any of those are prerequisites for investing in technology companies. I have tried to incorporate what I have learned from technology companies in the market into the valuation, in the form of easier scaling up, larger networking benefits and bigger market effects, but I might not have done it well enough.There are many who know a great deal more about ride sharing than I do, and while I have tried to learn about the inner workings of this business from Harry Campbell and about the Chinese growth potential from Drake Ballew, my ride sharing know-how is limited. Finally, if we did restrict writing about the valuation of young companies only to consistently successful venture capitalists, the list of potential writers would be very short, and most on the list would be too busy investing in these startups to write about them.

Whatever group you belong to, rather than complain about my mistakes or bemoan my limitations, please take my Uber valuation and make it yours, putting your superior knowledge and experience into the numbers. In fact, let’s give this a crowd valuation twist and get a shared Google spreadsheet going, where you can post your results.

To be continued..

To show you how much Uber has found its way into my every day thinking, I will end with a personal story. Towards the end of last summer, my youngest son, who was fifteen then, had a friend over for the afternoon, and when it was time for the friend to leave, I looked out at the driveway, expecting the “Mom car”, the typical mode of transportation for a 15-year old in the middle of suburbia.

When I saw a strange sedan with a bearded man in the driver’s seat, I was taken aback, until I was told that it was an Uber car. Since this happened only two months after my valuation of Uber in June 2014, where I labeled it an urban car service company, my first reaction after I got over my surprise was that I needed to value Uber afresh. Of such small thoughts are obsessions born!