At a conference last October, I encountered a fascinating “creature” named AVA that I mentioned in a blog post shortly afterwards.

Though extraordinarily helpful in keeping a conversation going with another conference attendee, AVA was not a person. She (or perhaps I should say “it”) was a telepresence-enabled robot that made it possible for an Internet of Things World Forum participant to attend the conference in Chicago while remaining physically in Germany.

Seeing AVA made a strong impression on me. So much so that earlier this year I ordered a similar robot to see if we could enable our team at the MIT Sloan School of Management’s Office of Executive Education to work remotely without missing out on more social aspects of work-life in the office.

We already were using the usual array of remote working technologies—chat, video conferencing, the ubiquitous email, and even virtual-reality avatars—but I was noticing that teammates who work mostly or entirely remotely seemed still to be at a disadvantage. It is too easy to forget the person on the phone in the middle of the conference table, or even waving frantically at you from the big screen at the end of the room, and those people certainly do not benefit from all the side conversations or spontaneity of being able to drop into a colleague’s office for a chat.

In contrast, we are finding that the telepresence robots (we now have three of them for an office of 35 staff) give our remote colleagues a level of human engagement that helps us to work well together.

Our robot is essentially an iPad on wheels that a remote user can operate and steer around the building using a web browser or iPhone App. They can drive themselves into a conference room or to another person’s office, for instance, or even to a water cooler or lunch table. The remote user gets an eye-level view of the people they are engaging with, and their more or less life-size face is at eye level for us too. This way, we have found, they can be part of conversations in a much more natural and organic way.

We have also started to experiment with the telepresence robots as a way to attend executive education programs, to give participants who are unable to be there in person the ability to take part in the learning experience in a more meaningful way than a traditional video link or webcast. We still believe very strongly, of course, in the power of getting together in person, but when that is not possible or practical, telepresence robots seem to be a viable alternative.

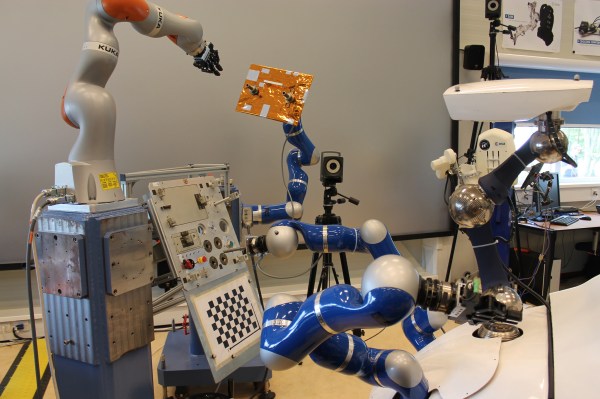

Space Tech Moves Closer To Home

Telepresence robots are an example of the much broader field of telerobotics, an area of engineering that has been moving steadily away from science fiction into our everyday lives. Telerobots, simply, are robots that are controlled by people to perform tasks remotely. Like many technologies that we take for granted today, telerobotics got its start (and early R&D funding) in the space exploration and military fields. For example, Curiosity rover made it possible for NASA researchers to gather data on the surface of Mars. And we are now sadly familiar with the image of remote controlled robots being used to defuse improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

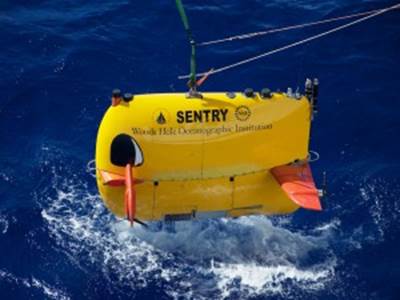

Another example that started with a defense application and spawned major scientific, educational and commercial outcomes was pioneered by the legendary deep-sea explorer Dr. Robert Ballard from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. He famously used remotely operated submarines in his discovery of the Titanic’s wreck and many other famous shipwrecks. Today, WHOI scientists are using robots to virtually connect classrooms with underwater expeditions in real time, so that students can experience the excitement of exploration and discovery first-hand.

Autonomous underwater vehicle Sentry

Telepresence robots are being used in a wide variety of other applications ranging from medicine to toxic waste cleanup to art installations. In hard-to-reach communities in Canada, a telerobot named Zeus serves as the eyes and hands of Dr. Mehran Anvari who performs surgeries remotely from St Joseph’s Hospital in Hamilton, Ontario.

As of last year, Dr. Anvari has conducted over 20 operations using telecommunications, robotics, and skilled nurses on site. “It’s the same as if I were sitting in the operating room,” he told the BBC. “I have both my hands on the robot the same way I would have instruments in both hands.”

Closer to home, researchers from MIT’s Department of Mechanical Engineering have built a bipedal robot named HERMES that has human split-second reflexes, allowing it to balance while performing complex tasks. The engineers envision HERMES being very useful at disaster sites and other dangerous environments, with its precise movements controlled by a remote human operator.

HERMES punches through drywall while keeping its balance, guided by a human operator.

Telerobotics, Telecommuting and Accessibility

These and countless other examples of people using robots to perform work remotely made me wonder how tremendously useful this could be for making more workplaces accessible to people with physical disabilities. It’s important to note the difference between telepresence and telecommuting, which has been a popular option for people with mobility challenges.

A growing trend in many industries, telecommuting is actively promoted by organizations that help people with disabilities find meaningful employment. Work Without Limits, a Massachusetts network of engaged employers and innovative, collaborative partners that aims to increase employment among individuals with disabilities, cites telecommuting as a highly useful tool for employers interested in making their workplaces more accessible. I wrote about our engagement with this fine organization in a previous post.

However, telecommuting has recently come under legal scrutiny as a “reasonable accommodation” per the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Just like the Ford Motor Company that was the beneficiary of the Sixth Circuit Court decision when it reversed its previous opinion to grant telecommuting as “reasonable accommodation” to a disabled employee, many employers are resistant to telecommuting, insisting that work tasks need to be performed face to face.

Perhaps telepresence robots could help solve that problem by allowing employees to engage with colleagues, vendors, or customers not only in real time, but also face to face (via robot), and be able to “move around” an office or a manufacturing floor?

Regardless, I hope that more enlightened employers will see the merit of expanding their mindset beyond “reasonable accommodation” and into “enabled workplace” for everyone.

In the future, no doubt more advanced assistive technologies, prosthetics, “bionics,” new therapies, and the like being developed at MIT and elsewhere, will have profoundly beneficial impacts for people living and working with mobility challenges and disability (both physical and cognitive.) With an ageing population, of course, that will be an increasing number of us!

Enter Machine-Enabled Workforce

In their best-selling book “The Second Machine Age,” my colleagues Erik Brynjolfsson, professor of Management at MIT Sloan, andAndrew McAfee, co-director of the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy, discuss some very serious concerns about robots replacing people in the workforce. According to their findings, robots today are taking over not only the areas of work that benefit from automation—like factories, warehouses, and distribution centers—but also “knowledge work” that requires performing complex cognitive tasks. In the opening chapter, the authors warn us about “the second machine age unfolding right now.”

They see it as “an inflection point in the history of our economies and societies (…) but one that will bring with it some difficult challenges and choices.” Despite some rather grim predictions, Brynjolfsson and McAfee are optimistic about the future of work.

And so are the authors of a recent Harvard Business Review article Julia Kirby, editor at large at the Harvard Business Review, and Thomas Davenport, professor of Information Technology & Management at Babson College. Kirby and Davenport outline five highly tangible approaches that humans involved in knowledge work can take to remain relevant and successful in the workforce of the future.

Combining telerobotics with other technologies that are already enhancing our work and living spaces could be a great boon to employers looking to tap into diverse talent pools. In its Global Human Capital Trends 2015 report, Deloitte lists “Machines as Talent” as one of the major trends and encourages Human Resources professionals to “focus on the opportunities cognitive technologies offer through collaboration between people and machines to help make companies more efficient, productive, and profitable, and jobs more meaningful and engaging.”

As MIT Sloan professor of Management and Information Technology Thomas Malone said, “the future of work is not man v. machine, but man plus machine.” You can learn more about the subject in Prof. Malone’s new online executive education course, Intelligent Organizations 4DX, in which he and all the program participants will be meeting as avatars in a 3D virtual-world classroom.

Happy Humans Are Better Workers

Here at MIT Sloan Executive Education Office, we are definitely not replacing our people with machines, but instead we are using telepresence robots and other information and organizational technologies to help our people to be more productive and, we hope, happier workers.

We want to make sure that people working remotely or in a different time zone are able to fully participate in the work-life of the office. We want to allow people to work more flexibly in time and place. However, we are not expecting anyone to work around the clock just because they are not in the office physically.

We have built a structure that seems to be working well so far. About two thirds of our employees work remotely one to three days a week and we only ask everyone to be in the office in person if possible on Wednesdays. We try to hold internal meetings between 10:30 am and 4:30 pm, we discourage meetings before 8:30 am or after 5:30 pm, and encourage everyone to be thoughtful about the work patterns and preferences of others on the team, while still, of course, doing what we need to do to get things done efficiently and effectively.

As I explained in a recent interview, what we are finding is that even allowing for some of the challenges of physical distance, people who work remotely can contribute just as much if not more because they are getting so much back from not wasting time commuting, for example. Overall, morale and outcomes have improved, as, crucially, has our agility as an organization. These facts are not disconnected.

As a manager, I value very much all the extra work that people on my team are able to do as a result of these new ways of working. As a leader and human(e) being, though, I value even more how these innovative working practices and technologies are helping us achieve the goal of being a better place to work for all.