Earlier this summer, more than 35,000 industry leaders gathered at Mobile World Congress Shanghai 2015 to discuss the future of mobile, making it the largest-ever mobile-focused event in Asia. Whereas the majority of the conference focused on new technologies such as 5G and Internet of Things, I was joined by peers from Netflix, Line, Ola Cabs, Flipkart and Twitter to discuss future business models for the mobile Internet.

Most of this discussion steered toward China and India, but I was there to focus on Southeast Asia. This perspective (or some would say, bias) isn’t just because my company operates in Southeast Asia, but rather is because of our $16 million dollar bet that innovation and disruption in mobile will be coming out of Southeast Asia far faster than other regions, such as the U.S., China and Japan, as expected.

Why? I will argue below that Southeast Asia is at the crossroads of two major socio-technical forces that are creating a perfect storm scenario: the convergence of “no-tail” and “mobile leapfrogging.”

No-Tail: Southeast Asia Jumped Straight Into Web 2.0 And Commerce Will Outlive Ad-Driven Business Models

Remember the early millennial heyday of GeoCities homepages, and later the evolution to self-publishing/blogging, user-generated content? That glorious era of Web 1.0 and, more importantly, Web 1.5 in Western markets was what gave birth to a monolithic monetization model around ad networks like Google AdSense and premium ad networks through an ecosystem of “long-tail” publisher content on platforms such as Blogger.com, MovableType and WordPress.

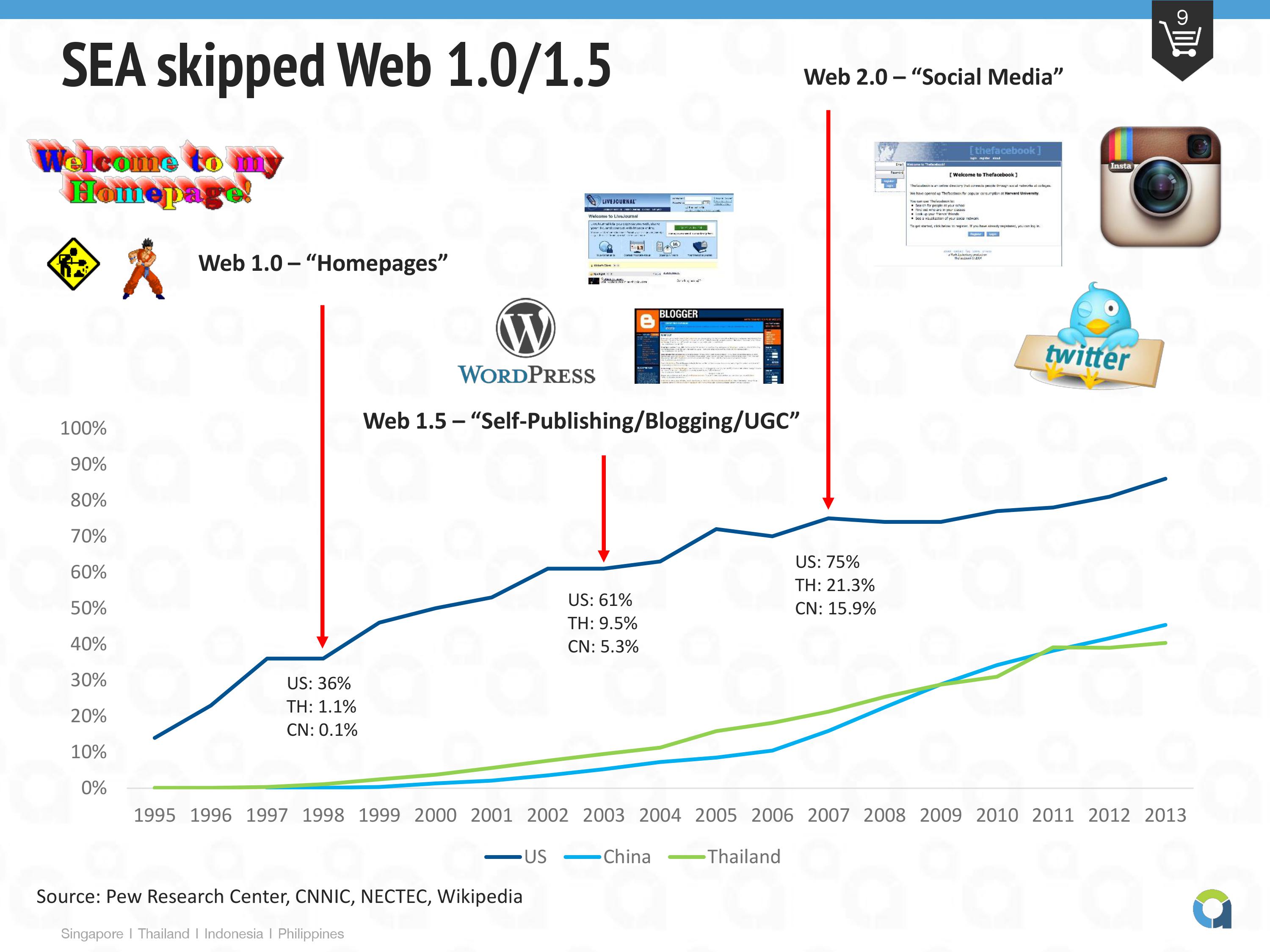

But in Southeast Asia, the Internet took off a bit later than its Western counterparts, when a tiny little site like Facebook was already most Asian Internet users’ first online experience — the end of the Web 2.0 wave, which hit Thailand in 2007 when Internet penetration crossed the 20 percent mark.

We use Thailand as a proxy for Southeast Asia because the country is the most developed one in the region (excluding Singapore/Malaysia) and, unlike Singapore/Malaysia, most VCs tend to agree that the trends and lessons learned in Thailand apply across the rest of the region, especially in upcoming major markets such as Indonesia, Philippines and Vietnam.

If you compare Internet penetration data from the U.S. and Thailand, you’ll notice that the U.S. went through the Web 1.0 and Web 1.5 booms while having significant double-digit Internet adoption rates of 36 percent and 61 percent, respectively. In Thailand, this number was in the dismal single digits during the same periods. It wasn’t until Web 2.0, around 2007, that Thailand started to see Internet adoption take off rapidly, significantly contributing to the growth of national GDP and e-commerce.

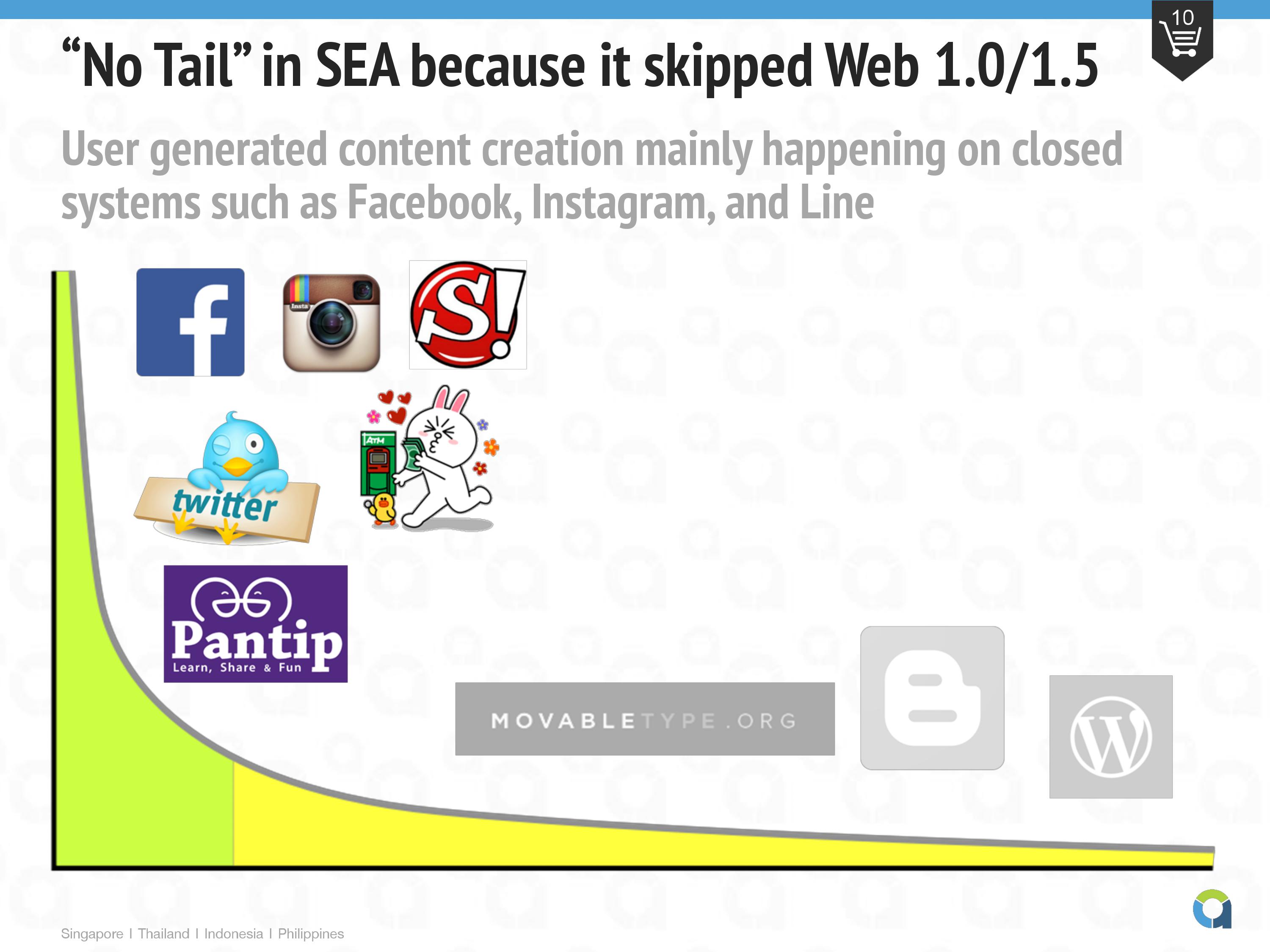

Coming to the Internet party late resulted in user-generated content creation going straight onto closed social media systems such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter — in effect, what marketers languished calling a “no-tail” landscape with lack of quality long-tail publisher inventory.

Because of the lack of this long-tail in Southeast Asia, the online advertising industry has lagged behind, forcing both established firms and startups to look for non-advertising-based monetization sources. Enter e-commerce and digital goods.

From Traditional Ad-Driven Monetization Toward Hybrid And Commerce-Driven Business Models

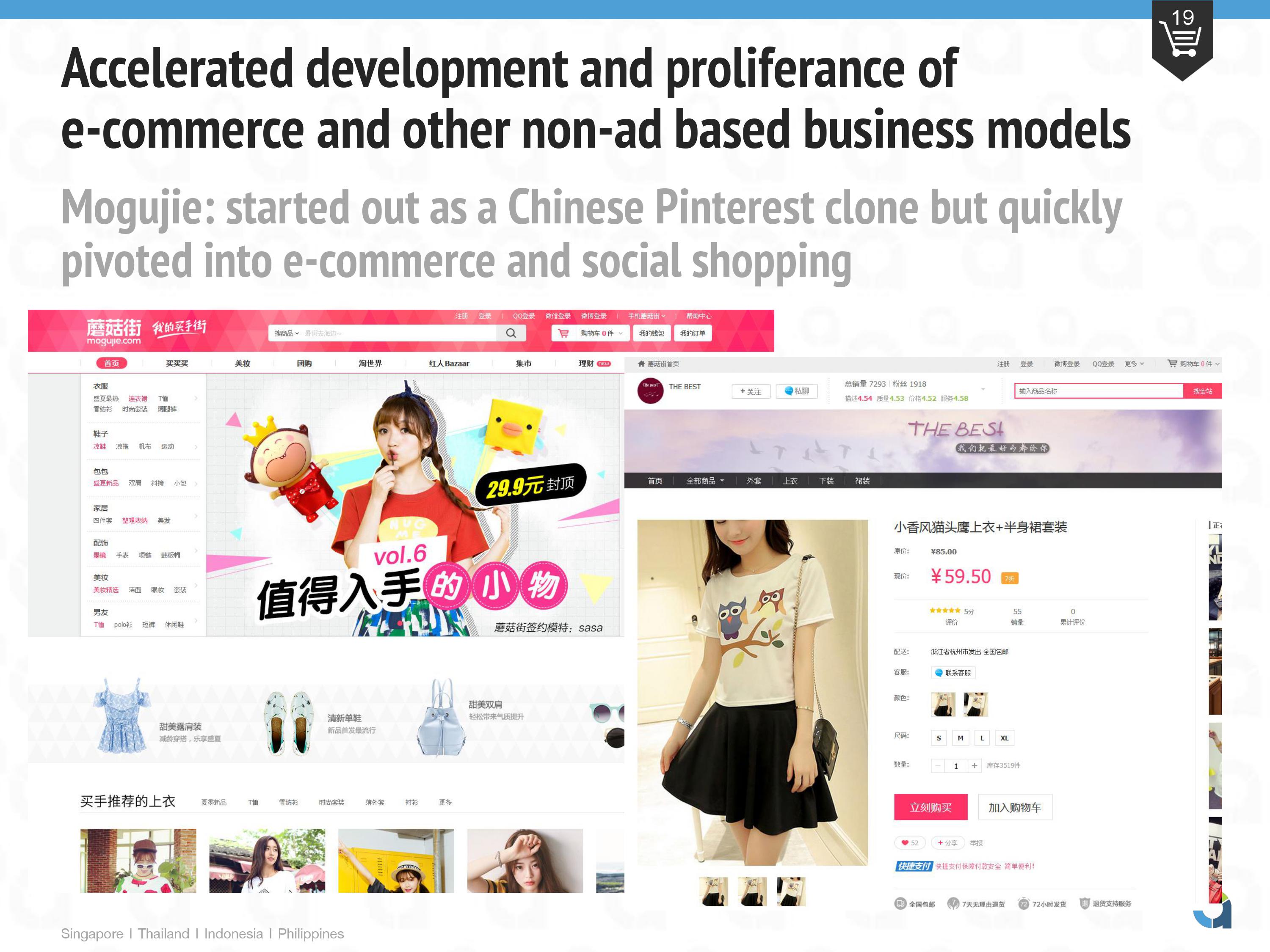

One of the more interesting effects of “no-tail” is the accelerated development and proliferation of unique and Asia-specific business models. This is where the Asian culture and ecosystem meets local ingenuity and entrepreneurship. Whereas startups and Internet companies in the U.S. have a tendency to go with advertising as their default monetization strategy — see Pinterest (Promoted Pins), Instagram (Carousel Ads) and recently Snapchat (“Vertical, Video, Views”) — Asian businesses in our space have had to look elsewhere to make money.

China’s Tencent is the poster child of this. The company generates more than 80 percent of their revenue from VAS (value added services, mainly virtual goods) and e-commerce. Less than 10 percent of their revenue is from selling banner ads and search keywords. Another example is Mogujie, a female-focused social shopping site that raised more than $200 million before being acquired by Alibaba. Mogujie started as a Chinese Pinterest clone, but quickly pivoted into e-commerce and social shopping. Unlike Pinterest, who makes money off “Promoted Pins,” Mogujie struggled to monetize through advertising and had to move into e-commerce to survive.

The same thing is happening in Southeast Asia as it follows a similar path as China because of similar ecosystems. Publishers are seeking help to monetize through e-commerce because they struggle making money from selling ads through ad networks. For example, based on average Thai RPMs (revenue per 1,000 impressions/page views), a popular local vertical publisher like Cosmenet.in.th will only make $350 per month based on page view numbers from SimilarWeb. This isn’t even enough to cover hosting fees, which is why it’s not surprising that these publishers are looking for non-traditional monetization channels such as e-commerce.

Mobile Leapfrogging: Southeast Asia Is “Mobile-First” — How This Will Be The Breeding Ground Of Future Business Models

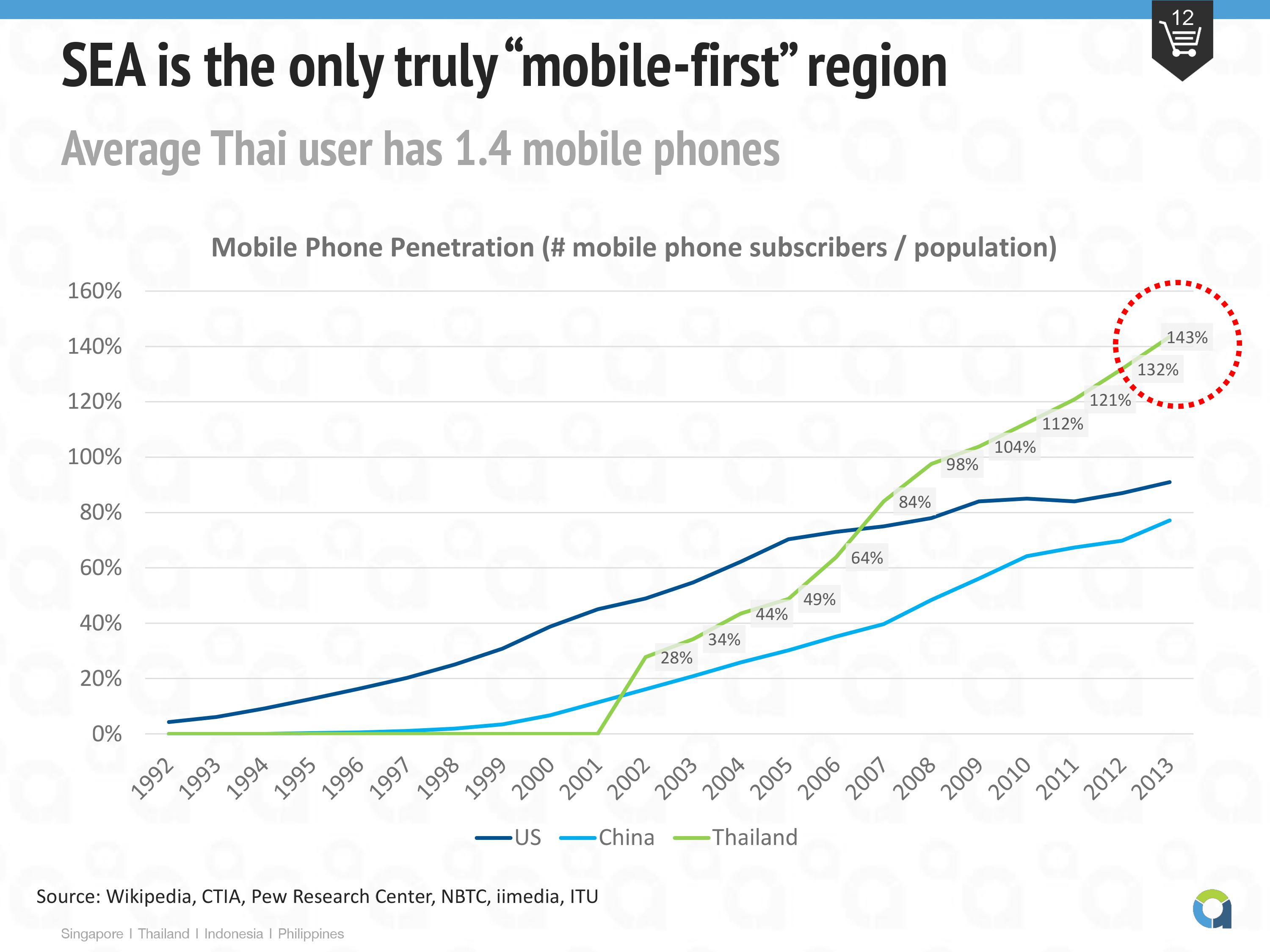

Everyone talks about how China and India are going to be the next big thing in mobile, which is not surprising because of how massive those markets are. However, if you normalize the numbers and look at mobile phone and mobile Internet adoption rates, Southeast Asia is actually the more interesting case.

The Average Thai User Has 1.4 Mobile Phones

Mobile phone adoption has skyrocketed in the recent years in Thailand with the latest numbers outpacing the U.S. and China in terms of mobile cell phone penetration. Unburdened by a desktop Internet legacy and driven by ever lower costs of smartphone manufacturing, cell phone adoption in Thailand has accelerated to a point where the average Thai person has 1.4 mobile phones, or 140 percent adoption. Compare this to the U.S. and China, which are “only” seeing 91 percent and 77 percent adoption rates, respectively.

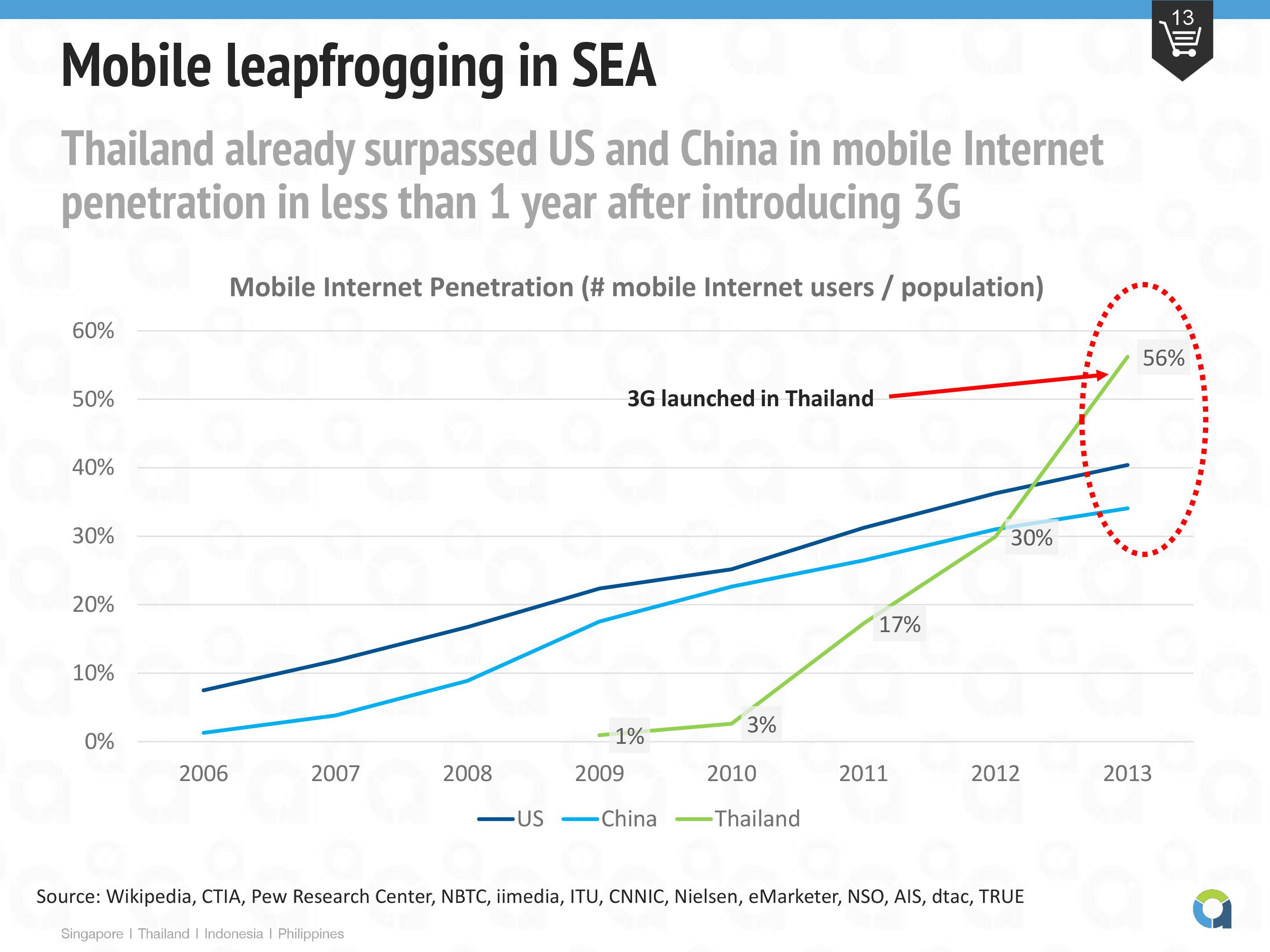

Mobile Leapfrogging: Thailand Has Surpassed The U.S. And China in Mobile Internet Penetration In Less Than One Year After Introducing 3G

Mobile Internet penetration in Thailand has jumped from a mere 1 percent in 2009 to a whopping 56 percent in 2013, with the bulk of the growth coming right after the country’s official 3G launch in early 2013. Mobile Internet adoption in Thailand beats mature markets such as the U.S. and China, which stand at 40 percent and 34 percent, respectively.

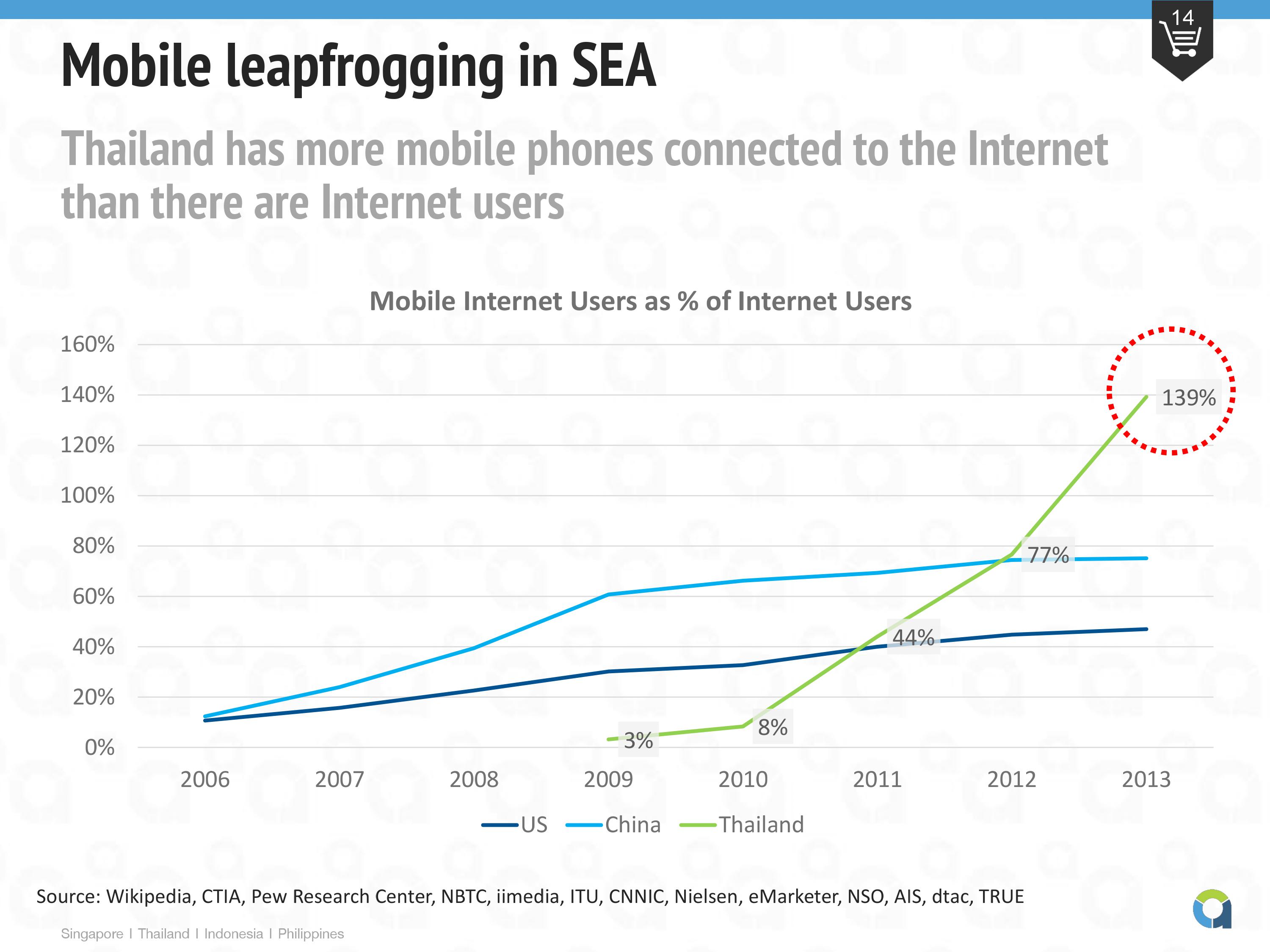

Another way of looking at this is by analyzing the percentage of mobile Internet users out of total Internet users. For Thailand, this number is 139 percent, meaning that Thailand has more mobile phones connected to the Internet than there are Internet users. Thailand pummels the U.S. and China, whose numbers are 47 percent and 75 percent, respectively.

Companies in Southeast Asia are noticing this trend and are quickly adapting to it. For example, Lazada now gets more than 50 percent of their traffic from mobile channels after making app development a priority. They’re also one of the first e-commerce players in Southeast Asia that launched both their iOS and Android apps. MatahariMall, Lippo Group’s new e-commerce venture, started with their mobile website and worked backward to create their desktop experience. Others, such as SaleStock, a fast-growing fast-fashion e-commerce site in Indonesia, are foregoing desktop completely and only provide a mobile, albeit non-native, shopping user interface.

The Perfect Storm: No-Tail Meets Mobile Leapfrogging — A Peek At The Future Of Mobile Business Models In Southeast Asia

At the crossroads of “no-tail” and “mobile leapfrogging” we can expect to see a melting pot of new and unique mobile business models to Southeast Asia.

C2C Models: The Six Steps To Quick Social Commerce In Southeast Asia

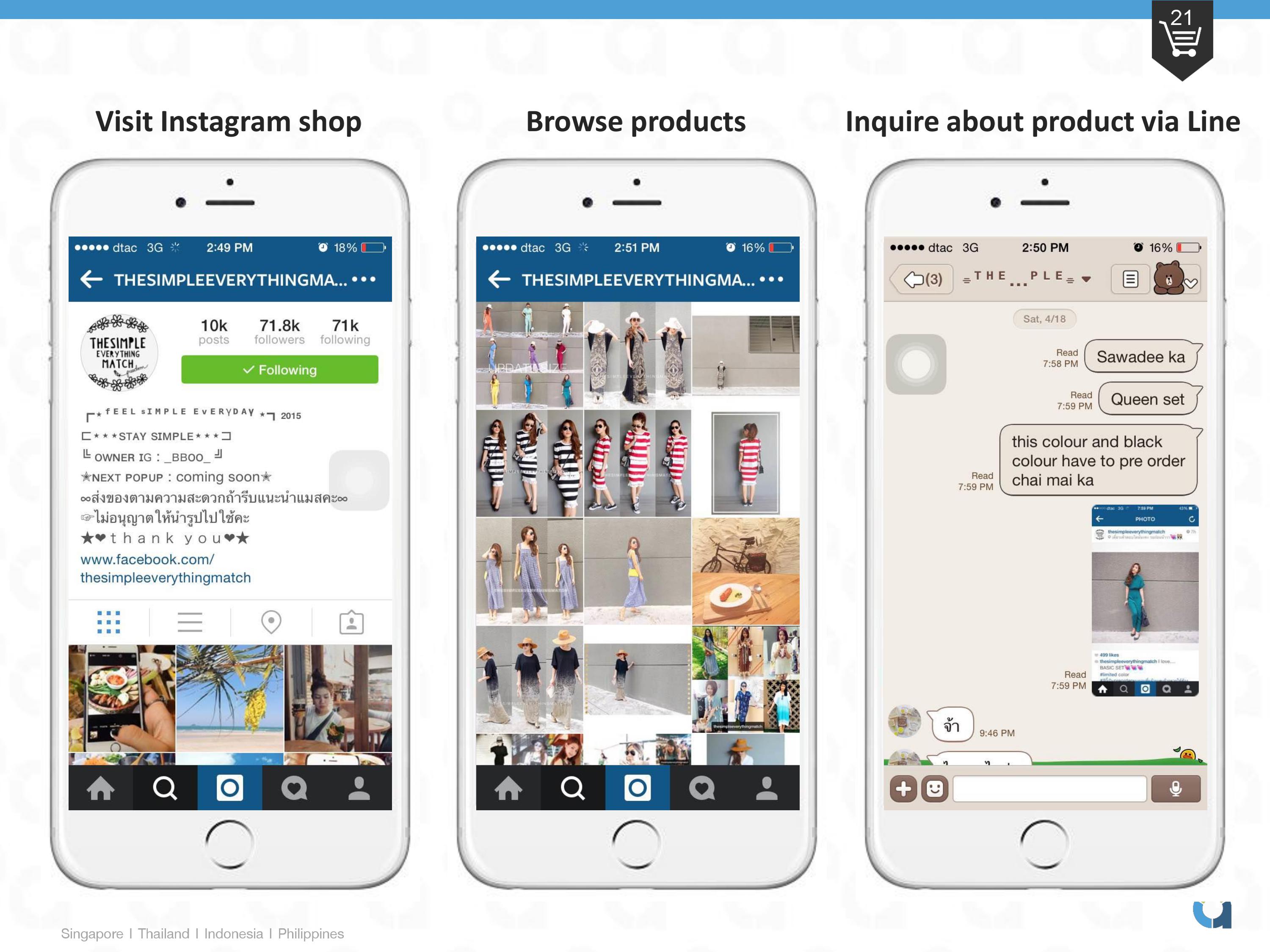

One interesting, and uniquely Southeast Asian, phenomenon is “shadow marketplaces.” Because of the two forces in play — high mobile penetration and content creation concentrated on social media platforms — there’s been a rise of informal C2C e-commerce on social media, such as Instagram, Facebook and Line. These are not your small mom-and-pop stores that sell bits and pieces here and there — an estimated and whopping one-third of total Thai e-commerce GMV comes from transactions happening on these shadow marketplaces.

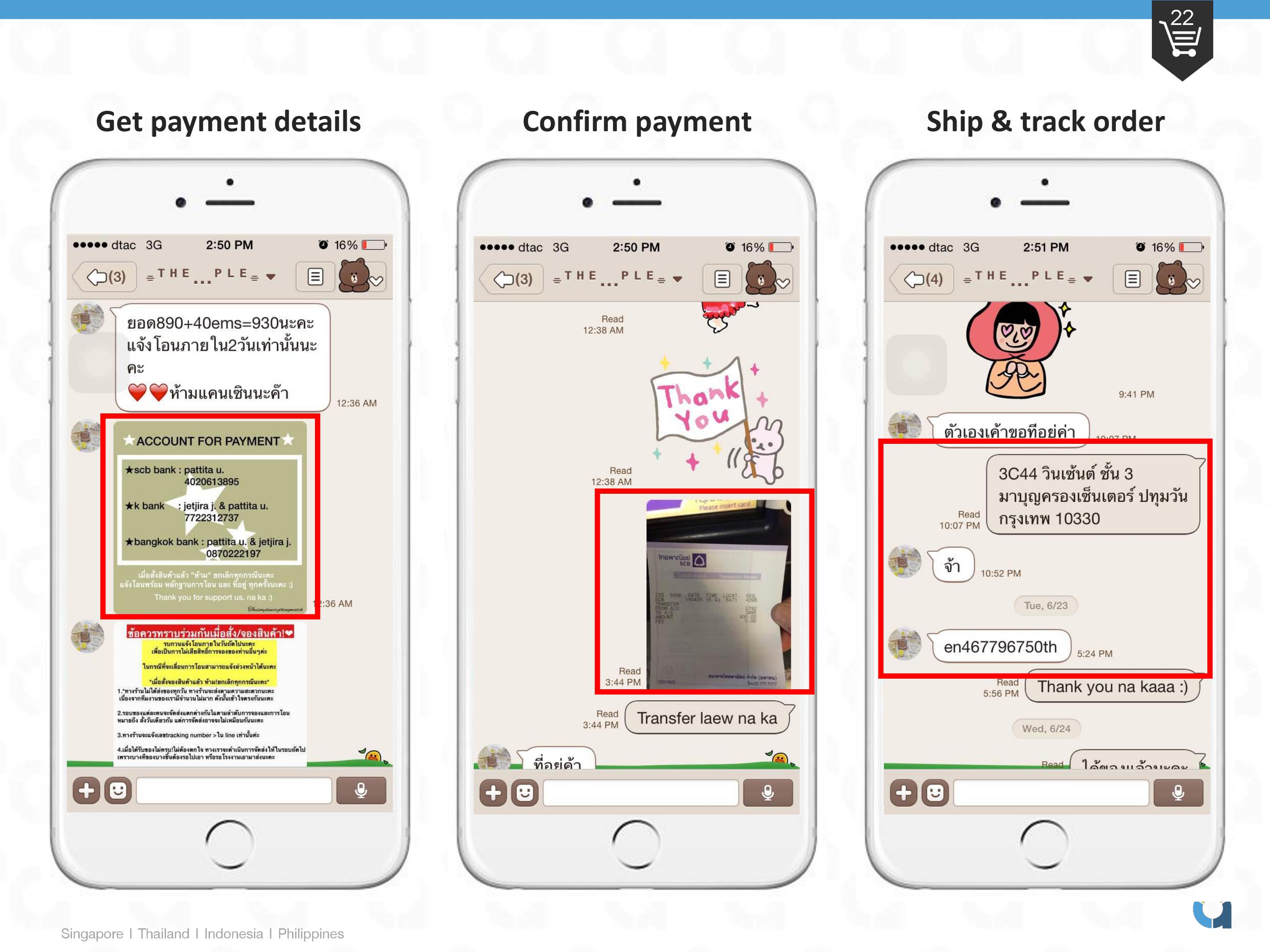

This is how it works: Merchants feature their products on Instagram and the transaction is completed via Line messaging, the most popular chat app in Thailand:

This may seem very low-tech to many of us who are used to more “advanced” and seamless e-commerce shopping on platforms such as Amazon and Tmall, but the societal and economical impact it has on e-commerce in Southeast Asia cannot be ignored.

B2C Models

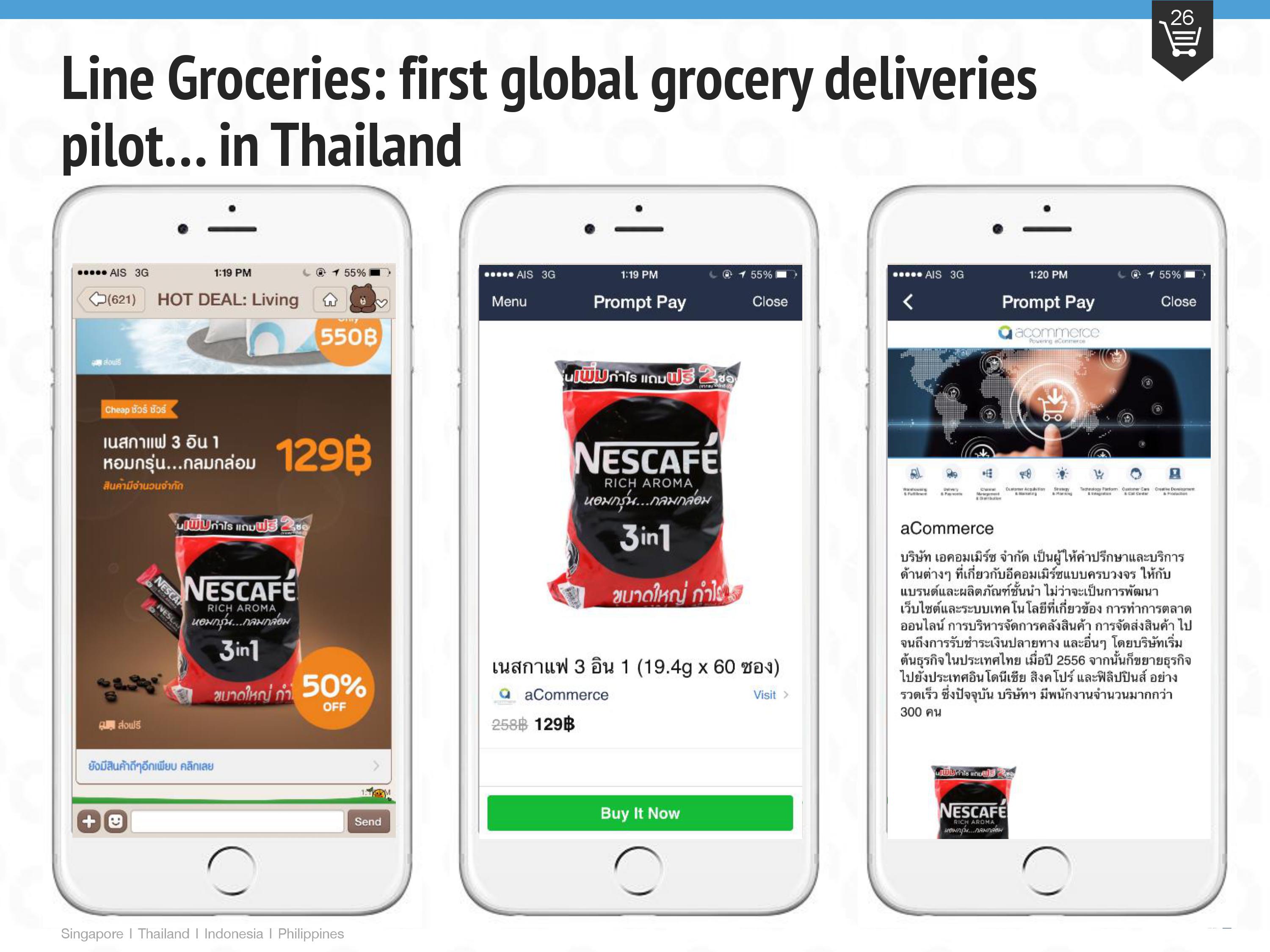

At the Mobile World Congress panel, I shared the stage with Hanna Lee from Line Corp. She’s the GM for Line’s China and Hong Kong business. Hanna showed Line’s evolution from a messaging app to a total media solution covering digital goods, music and video. In Southeast Asia, realizing the shift toward mobile commerce, the same company has launched several pilot projects to tap into e-commerce monetization, most notably Line Flash Sale, Line Hot Deal and Line Groceries.

Line Groceries launched first in Thailand because it’s Line’s second-biggest market outside of Japan, with more than 29 million users out of a total 600+ million users. This is proof that big players like Line are foregoing launching in their largest markets, like Japan, and jumping straight into the most fertile grounds for testing new and innovative business models.

B2B2C Models

We’ve recently seen players like Pinterest, Facebook and Google going aggressively into e-commerce for monetization. Earlier last month, Google announced “Purchases on Google” enabling buy buttons on mobile. The same day, Facebook started testing digital stores with a buy button for Facebook Pages, joining the ranks of Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest who ventured into buy buttons in the months prior. All these firms are looking into e-commerce as an additional, albeit lucrative, revenue stream.

However, in Southeast Asia, this may not be a luxury feature compared to mature markets like the U.S. and Europe. Instead, enabling e-commerce through buy buttons may be a necessity, and even a survival mechanism, because the market, as we argued before, is commerce-driven, not ad-driven. Also, given the perfect match of supply and demand in Southeast Asia as we’ve seen in the shadow markets case, we expect adoption of buy buttons to be much faster here.

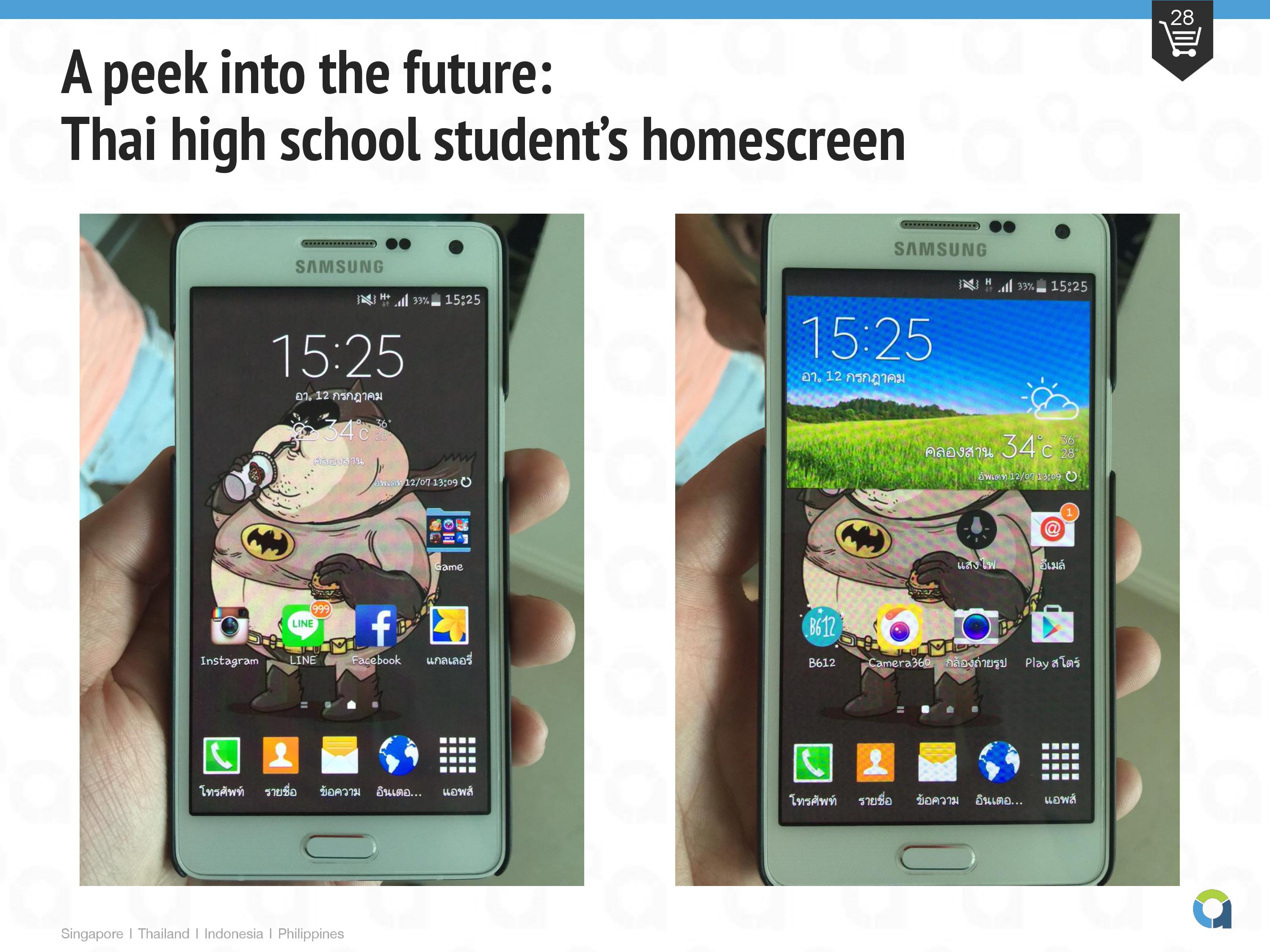

Given the plethora of established e-commerce platforms available, even in an emerging market like Southeast Asia, one would wonder why Google and Facebook enabling e-commerce is such a big deal. A quick look at actual mobile behavior in a market like Thailand helps us connect the dots. Below is an image that shows two mobile phone home screens of a Thai high school student.

Screen one, on the left, shows social media and chat apps like Instagram, Facebook and Line, in addition to a folder dedicated to games. The other screen shows nothing but camera apps.

Three interesting observations can be made here:

- There’s no Google. Despite Google’s recent massive numbers, as well as media newly proclaiming that mobile isn’t ruining Google’s search business at all, it would be interesting to see these numbers broken down by market, especially Asia and specifically Southeast Asia. Blending numbers and behavior across markets doesn’t reveal the true impact of a “mobile-first” or “mobile-only” market like Southeast Asia. Don’t get me wrong — Google Search is here to stay, even on mobile. However, its impact will be less prominent in our mobile age. As a MediaPost commentary points out: “In a sense, then, the rise of mobile means that — in some cases — search engines are being leapfrogged; we’re going directly to familiar, popular or mobile-friendly channels without visiting a search engine first.”

- There’s no YouTube. Video is moving to Instagram, Facebook and messaging apps like Line. Facebook now has more than 3 billion video views per day. And Line recently launched a YouTube-like video service in — where else but — Thailand. Line picked Thailand over its biggest market (Japan) for this launch because Thailand, not Japan, is a truly mobile-first market.

- There are no commerce apps. Granted, this is an 18-year old high school student in an emerging market, but as soon as habits are formed, they are very hard to change. Also, as discussed earlier, there may not be a need for commerce apps at all as Instagram, Line and Facebook already are becoming the de facto commerce platforms in Southeast Asia. Facebook, Instagram and Twitter officially going into buy buttons will only reinforce this, especially in this region. This phenomenon with the next generation will pose a major challenge to established e-commerce retailers and platforms in Southeast Asia, given how dominant Facebook, Instagram, Line and Twitter are in this region.

Conclusion

Driven by two unique forces, “no-tail” and “mobile leapfrogging,” Southeast Asia is in a special position to be the melting pot for new mobile business models. Stop looking at the U.S., China or even Korea/Japan for inspiration for the future of mobile, because it is not happening there. Ironically, mature and developed markets carry the heavy legacy of the desktop Internet era, whereas Southeast Asia started with a clean slate, allowing the latter to be in a unique position to experiment and develop new business models on mobile, primarily driven by commerce.