Given Google’s recent purchase of a building on the Embarcadero and the city’s move to effectively block Pinterest from relocating its headquarters into a specially-zoned building in the design district, I wanted to point out a few things.

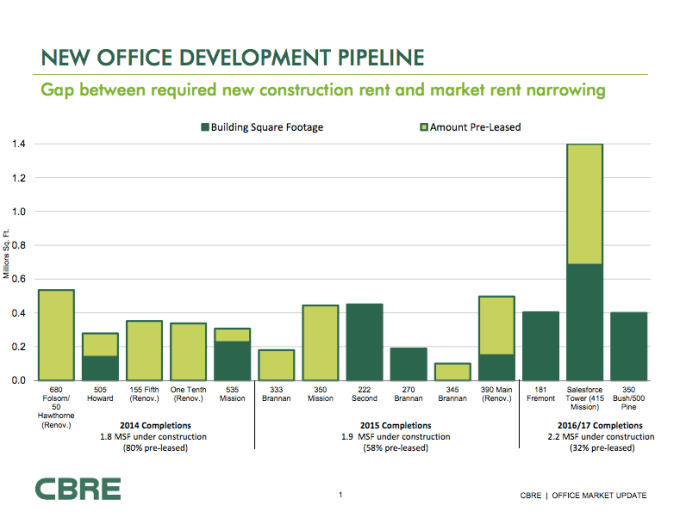

San Francisco is now at record employment levels after adding 60,000 jobs over the last four years. Commercial rents are hovering near their dot-com highs at $64.45 a square foot. Even though the city has the most aggressive office construction pipeline in the last thirty years, most of the space coming online in next two years is already pre-leased to tenants like Dropbox, LinkedIn and Salesforce (see below).

The city is about to run into a nearly two-decade old law called Proposition M that caps the amount of office space that can be built in any period.

Under Proposition M, there is an annual allocation of about 875,000 square feet that can go toward large commercial real estate projects in San Francisco. That amount rolls over into following years, so we have about 2 million square feet under Proposition M available for allocation. However, there are 8 million square feet of projects in pre-approval, so developers are scrambling to get their projects entitled in time.

There are good intentions that went into the San Francisco’s historically cautious approach to growth. Proposition M was created as the city erected the equivalent of thirty-seven Transamerica Pyramids between 1979 and 1985. Residents became concerned about the “Manhattanization” of the city as tall buildings ate into available sunlight, created wind tunnels downtown and encroached upon the historic enclaves of Italian North Beach and Chinatown.

But there are also consequences and trade-offs, as there are with any policy choices. Here are two architectural appraisals of San Francisco, taken 30 years apart:

This is October 2, 1983, when the city embarked on a strategy of restricted growth through the “Downtown Plan,” which was passed the year before Proposition M won voter approval:

“The plan, which was formally presented by the San Francisco planning department to the City Planning Commission last month, strongly limits the size and location of new skyscrapers, requires the preservation of several hundred older buildings, and sets specific design guidelines to assure that new skyscrapers are slender and tapered rather than boxy in profile. If it is adopted, it would give San Francisco the most restrictive downtown zoning of any major city in the United States. It is, moreover, one of the most complete prescriptions for growth any American downtown has been given, for it specifies, block by block, what should happen in this city’s now densely built-up downtown….

The plan is intelligent and sensitive in its sense of what makes this city special. It emerges out of an understanding that the need for continued growth must be balanced by a cautious, knowing sense of the past, and by a respect for what is small and psychologically comfortable.”

Here’s May 29, 2014, as the lack of new commercial office space creates economic pressures for ‘adaptive re-use’ of older buildings:

“Tech firms have taken over more than three million square feet of existing office and industrial space. That’s nearly the equivalent of New York’s new 1 World Trade Center. Driven partly by young tech workers’ desire to live in cities, the trend helps explain why those suburban office-park projects like Mr. Foster’s seem far behind the curve even before they’ve been completed.

The phenomenon is not entirely new, of course. Back in the 1990s, tech firms took over bunches of old warehouses with exposed brick, tall ceilings and no corner offices during the first dot-com boom. The buildings were cheap. Traditional downtown tenants like law and finance weren’t interested in them at the time.

This new wave is also opportunistic. But in a much hotter real estate market with lower start-up costs, it’s driven as well by a taste for “authenticity,” “character” and other buzzwords today’s tech firms love. At the same time, constructing anything new here is a major headache. The city is crippled by an obstructionist set of city planning rules — the consequence of local activism and a Talmudic bureaucracy. Legislation from the mid-’80s caps the total amount of new office space that can be built here. All this contributes to why adaptive reuse has taken hold.”

Competition For Existing Space

Because of the lack of office space coming online and changing aesthetic tastes, startups chose older buildings and warehouses in the first dot-com boom.

That continues to this day. I toured one of them earlier this month as Zendesk moved into a former department store built in 1909 on Market Street (pictured at the top). Its windows are framed by terra cotta Corinthian columns and the interior has exposed brick and bits of graffiti left over from years of vacancy. Two firms called Cannae Partners and Westport Capital Partners bought it in 2012 for $9.5 million and renovated it for another $9.5 million.

Zendesk’s new office on Market Street before it underwent a $9.5 million renovation. It was filled with pigeons, trash and all kinds of discarded junk.

The new office after renovation on Mid-Market street between 6th and 7th street.

While many of the city’s historic buildings are being preserved and renovated, the lack of office space is fueling a brutal competition between startups and lower-rent tenants like non-profits, many of which cater to nearby low-income communities.

Earlier this month, the city’s board of supervisors blocked Pinterest from moving into the Design Center because it would have meant displacement for dozens of design showroom tenants. The space wasn’t zoned for office use; it was specially zoned for production, distribution and repair-design (PDR). But there was an exception that allowed buildings designated as historic landmarks to convert to office uses.

The local supervisor for that district, Malia Cohen, who is running for re-election in November, tabled the landlord’s appeal to change the building’s zoning.

“This was about solving a problem in the most fair, equitable way possible,” said Cohen, who said that the decision would have set a precedent for more than a dozen nearby buildings with PDR zoning. “You’re more than welcome to come to San Francisco and have a business. But we are unwilling to sacrifice PDR space for office space, when you consider that office space is being actively built already and PDR space is not.”

Pinterest will likely have to look elsewhere. However, at the end of the last quarter, there were only six contiguous spaces of Class A office space with more than 100,000 square feet available in San Francisco. There are more than a dozen companies competing for these slots.

The Reverse Commute

The restriction on office space also contributes to Silicon Valley’s unusual reverse commute where tech workers bus in from San Francisco to the South Bay. After Proposition M passed, the amount of office space built annually declined to a trickle, partly because of the law and partly because of the economic fallout from the 1980s Savings and Loans Crisis.

Supporters of Proposition M point out that it saved San Francisco from a glut of office space and a spike in vacancy rates that cities like New York, Los Angeles and Denver saw after the boom ended late 1980s.

But it also meant that the center of the Bay Area’s workforce gradually shifted south as job growth favored Silicon Valley’s big suburban campuses and industrial parks. In 1985, San Francisco made up 22 percent of the Bay Area’s workforce. By 2012, the city made up 17 percent of the region’s workforce after ticking up again over the past decade.

That trend reversed beginning with the dot-com boom. In the 1960s, corporate interests envisioned that San Francisco would become a “world class” city and gateway to the Pacific with with workers commuting in via BART and the highways from the suburbs. But the city politically revolted against that vision in the mid-1980s, seeking to insulate residential communities from the boom-and-bust cycles of capitalism.

Instead, regional growth subverted that intent. While the city didn’t produce office space for major corporate tenants, everyone including the peninsula cities and historical Silicon Valley didn’t produce housing.

Hence, the reverse commute. Office rents are about one-third cheaper per square foot in Silicon Valley than they are in San Francisco, but the median rent for a residential listing in Mountain View is roughly the same as it is in San Francisco. So today, San Francisco’s neighborhoods and longstanding communities are beset by gentrification as tech workers move in.

San Francisco chose slow-growth policies in the early 1980s just as major cities on both U.S. coasts began a three-decade demographic trend of population increases that reversed post-war “white flight” to the suburbs. These policies and the lack of regional coordination exacerbated big economic and demographic shifts that are frankly beyond the control of any single city. The nuclear family waned, giving rise to more single Americans than ever before. Changes in the labor market meant more flexible employment with workers hopping into new jobs every few years. All of these transitions favor the serendipitous collisions made possible by urban environments.

If the city doesn’t revisit the caps, there will continue to be intense pressure and competition for existing space in old buildings, which will push out lower paying tenants. Tech may spill over into Oakland’s downtown district, where office vacancy rates hover at 15.5 percent compared to San Francisco’s 10.6 percent rate, which is the lowest nationwide behind New York and Portland. If current trends hold, commercial real estate firm Cassidy Turley says San Francisco’s vacancy rates may dip to 5 percent by year-end, driving rents higher.

If the city does revisit the caps — which will not affect office supply for years in any case — the region will have to figure out housing for all those workers too.

Tough choices loom ahead.