For about a decade from Facebook’s founding in February 2004 to Twitter’s IPO last November, the tech industry’s most visible successes were in social networking, or purely web or mobile-based software products.”

But today, the most interesting late-stage companies intersect with real-life services that have historically been both publicly or privately provided in a highly-regulated way. Think transit and housing.

Uber is valued (arguably) at $18 billion, and Airbnb recently raised funding at a $10 billion, making it worth more than Wyndham Worldwide or Hyatt Hotels.

The Ubers, Airbnbs and Lyfts of the world often get lumped together, but their approaches to regulation are actually fairly different. Despite the sometimes theatrical language, all of these companies have had to learn how to work with regulators. And if more startups intend to go into highly-regulated areas or if the tech industry wants to address the acute infrastructural and housing stress the San Francisco Bay Area is feeling, it will have to be active in both the public and private spheres.

Regulate at Scale

One de facto way has been to find product-market fit when you’re small, then to approach regulation at scale.

You could say that’s what Airbnb did. The company was founded back in 2008, way before there was any hyper-sensitivity or scrutiny around the tech industry. Unlike Uber or Lyft, Airbnb was accessible globally almost from the very start.

In the beginning, it was just two guys who needed to find a way to make their rent and decided to set up air mattresses for strangers during a design conference back in 2008. But by the end of 2012, they were seeing more nights booked than the Hilton Hotel chain.

Couch at the original Airbnb that Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia rented out.

But even though they’ve been based in San Francisco for six years, they still haven’t been able to reach a consensus around the legality of short-term stays in the city. Technically, you need a conditional use permit to offer residential rentals for less than 30 days.

Part of the issue is that in Airbnb’s case there are just many more kinds of regulatory bodies, laws and interests involved in hospitality and housing than there are in ground transit, where the point of contact might be the taxi commission and the primary opponents are the taxi medallion holders.

In highly desirable cities like San Francisco and New York, there’s also about 100 years of regulations and programs around building codes, public housing, inclusionary zoning and rent control that make housing something that’s somewhere between a privately-provided good and something that’s a resource for those who live and work in a community. Taken as a whole, these regulations aren’t necessarily coherent, but each component has its own rationale from providing affordable housing to maintaining scenic views or sunlight.

As the whole process has dragged on, Airbnb’s regulatory efforts have become more politicized and less predictable. In fact, there is now data suggesting that the volume of listings has either plateaued or is declining in New York and San Francisco as the company either cracks down on bad listings or new enforcement creates a chilling effect on listings. That could challenge that $10 billion valuation if some of the company’s most lucrative markets reach their natural size limits.

Right now, the company is actually facing two competing sets of possible regulation in San Francisco.

One set of rules was designed in collaboration with David Chiu, who is the current president of the city’s board of supervisors and is also running for a seat in the state assembly. It limits stays to 90 days per year and doesn’t supersede existing lease agreements, meaning that if a tenant hosts in violation of their lease, they can still face consequences like an eviction.

There’s a second more restrictive initiative that might go on the November ballot, put together by a former planning commissioner and affordable housing activists. It restricts short-term stays to neighborhoods that are commercially zoned. In addition, neighbors can file complaints about an Airbnb rental, go to court, and get 30 percent of fines and back taxes that result, along with their attorney fees. Updated: Under the revised version of the proposed ordinance, hosts would have to register with the city, offer proof that the unit’s owner allows short-term stays and have insurance that covers at least $250,000 per incident. They would be listed in a public registry and hosts would have to follow the city’s existing zoning codes, which could end up constricting Airbnb to a more limited set of neighborhoods in the city.

.@Airbnb opponents, supporters rally at S.F. City Hall. http://t.co/cFOfaNQ3Yq pic.twitter.com/qGLNKYaSI9

— SF Chronicle (@sfchronicle) April 30, 2014

A recent San Francisco Chronicle report scraped the site for listings and found that the platform touches about 1.3 percent of the city’s housing stock, or 5,000 units. Most of these listings appear to be occasionally rented out, but the Chronicle did find about 160 homes or apartments that appear to be on the platform full-time.

As I’ve explained before, the core reasons for the region’s current housing shortage go back many decades and have very little to do with Airbnb. Yet services like Airbnb do add pressures on the margins, especially when San Francisco is at record employment levels. The company appears to be holding its potential tax revenue, which it’s starting to pay this year, as a bargaining chip.

But given the fractious climate around housing right now, the company may be facing a showdown in its own hometown this November. The downside of waiting so long and getting big is that regulation becomes so politicized it becomes intractable.

Iterative Regulation

Uber and Lyft, in contrast, have had to roll out market by market, and work (or butt heads) with regulators from nearly the beginning. With a service like ground transportation, you can’t be global from day one because you have to carefully calibrate real-time supply and demand in every city.

Just three months after launch, Uber, then called UberCab, faced a cease and desist from the city’s MTA and the state’s public utilities commission. Lyft later launched peer-to-peer ridesharing and also faced a cease and desist. It took them about a year of discussions with state regulators to set rules for the services, which are called transportation network companies or TNCs.

But regulation is continuously changing. In the wake of a couple high-profile incidents including the death of 6-year-old Sophia Liu, the state legislature is now stepping in on top of the CPUC.

There are two statewide bills that would make insurance requirements more stringent on TNCs when drivers have the app open, but aren’t carrying or going to pick up a passenger, and strengthen background checks and alcohol and drug testing requirements. Lyft and Uber say these new insurance requirements are orders of magnitude larger than the normal $30,000 minimum required for all drivers, and that they’ve already stepped in with $100,000 of coverage when drivers have the app open but aren’t carrying or going toward passengers. They also have $1 million in liability coverage for when a car is either carrying or picking up a passenger.

The city of San Francisco, which doesn’t have jurisdiction over Uber and Lyft, is still tallying the financial impacts of the emergence of TNCs. They’ve calculated about $1.5 million in forgone fee revenue from the airport and up to $500,000 in lost business license revenue because drivers aren’t registering with the city as independent contractor businesses. The city also found that pick-ups of disabled paratransit passengers are down by almost half because there simply aren’t as many vehicles available.

Those issues seem like they should be fixable, but there are deeper tensions with drivers who are upset about their lack of job security if they get a poor rating and declining fare revenue. I suspect as drivers get more organized, Uber and Lyft will be pressured to find new compromises.

But again, the difference in their case versus Airbnb’s is that they can operate legally, even if that regulation evolves over time.

What do the lessons of the past tell us?

If you look at a hundred and fifty years of transit history in the San Francisco Bay Area, it’s a mix. There are big projects like BART and the Golden Gate Bridge that could have only been done with public money, and then there are many areas where privately-held companies have led the way.

It was eight privately-held companies that introduced San Francisco’s iconic cable cars.

Similarly, it was a private stage coach line that connected San Francisco to San Jose during the Gold Rush. It cost $32 and took nine hours for a one-way trip.

The plaza at Clay and Kearny streets where the stagecoach between San Francisco and San Jose left during the Gold Rush. From FoundSF.

Then less than 15 years later, a peninsula railroad opened that cost $2.50 for a 3 1/2 hour journey. It was then consolidated under the politically powerful Southern Pacific Railroad and then a century later, it became Caltrain.

From around 1915 until the mid-1970s, there were also hundreds of private jitneys that competed with MUNI.

That’s why I generally view this younger wave of bus startups like Chariot, Nightschool and Leap Transit favorably. MTA is simply not moving fast enough on bus rapid transit lines, in part because the city isn’t able to stand up to car owners and remove the requisite parking spaces that make dedicated bus lanes possible.

A bus rapid transit line on Van Ness Avenue has been in discussion since 2001 and will only be fully opened by 2018.

That’s seventeen years.

In contrast, it took Mexico City three years from idea to implementation on BRT. Unable to finance a full metro system, Bogota, Colombia has had a BRT system for more than a decade that handles 1.9 million passengers per day.

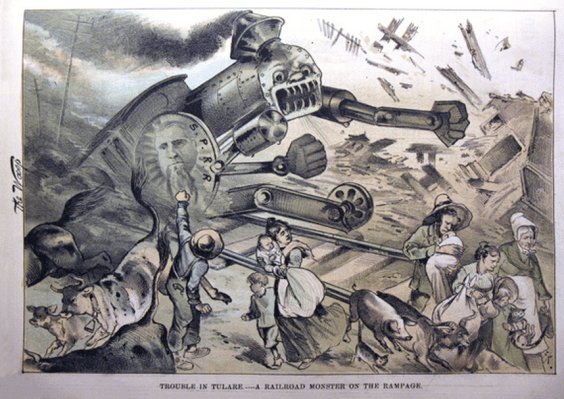

And yet, the history of California at various inflection points in transit technology bears enormous lessons about the consolidation of power among private entities and its long-term, unforeseen consequences.

Southern Pacific, a transit monopoly from a previous age in California. Leland Stanford, its one-time president, went on to found Stanford University after the death of his own child. He said, “The children of California shall be our children.”

Why, for instance, does California have this unique tradition of direct democracy through the ballot initiative, referendum and recall?

It was a political response in the early 20th century against the consolidated and corrupt power of the railroad barons, famously recounted in Frank Norris’ The Octopus.

Why, for instance, are corporations considered persons under the equal protection clause of the 14th amendment?

One of the cases it dates back to was a tax dispute between Santa Clara County, the original heart of Silicon Valley, and Southern Pacific Railroad. Yes, that’s Leland Stanford’s Southern Pacific.

The East Bay and Oakland used to have streetcars under the old Key System until National City Lines, a company backed by General Motors, Standard Oil, and Firestone Tires, converted them to bus routes. Key Transit eventually became the publicly run AC Transit when they were bought out.

Then if you fast forward a half-century to the rise of the automobile, a company backed by General Motors, Standard Oil and Firestone Tires called National City Lines bought out streetcar operations throughout the United States, dismantled them and converted them into bus routes. This includes the East Bay’s Key Transit, which eventually became AC Transit, and the Los Angeles Railway. It’s debated whether this was conspiratorial or just in line with changing consumer tastes; cars were considered a more democratic technology at the time.

The general lesson is simply to distrust the consolidation of power, whether it takes form of the Big Four railroad barons, the Big Three automakers, the taxi cartels or even MUNI, which has tens of millions of dollars in troubling accounting discrepancies on its $1.6 billion Central Subway project.

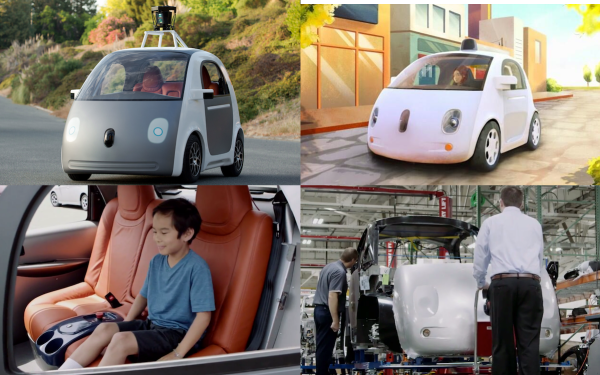

If we assume the partnership between Uber and Google, with its self-driving cars, represents another major technological shift in transit, there are lots of reasons to be wary even if the intentions are good. What will decreased car ownership and then self-driving cars do to patterns of urban and suburban development? Will it encourage sprawl? Will it increase Marchetti’s constant, the roughly one-hour commute that urban planners think residents can bear?

With Google’s self-driving car and its investment in Uber, what does the future hold?

The broad point is you can’t resort to ideological shortcuts around regulation versus de-regulation. It changes over time depending on the size the players, whether they are public entities, regulated incumbents or newcomers.

In Peter Thiel and Blake Masters’ forthcoming book, “Zero to One,” the famously contrarian venture capitalist argues that competition is a distortionary ideology.

“Americans mythologize competition and credit it with saving us from socialist bread lines. Actually, capitalism and competition are opposites. Capitalism is premised on the accumulation of capital, but under perfect competition all profits get competed away. The lesson for entrepreneurs is clear: if you want to create and capture lasting value, don’t build an undifferentiated commodity business.”

He goes onto explain that what entrepreneurs really want to identify is a creative monopoly.

Moreover, he says that monopolists are ultimately incentivized to lie about their true nature. So when companies trot out rhetoric about stifling innovation and competition, it’s hard to know when that transitions from something that’s genuinely in the public interest to something that obfuscates rent seeking.

In certain markets like San Francisco, TNCs appear to be dominant and deserve greater scrutiny around how they treat drivers and handle pricing. In other newer markets throughout the U.S. and continental Europe, they’re merely just one competitive choice among many and should be welcomed.

In certain markets where the housing supply is severely constrained, it makes sense to limit Airbnb rentals to a fraction of the year to disincentivize hosts from taking entire rent-controlled units off the market that were intended for long-term housing. In resort towns that are heavily dependent on tourism revenue, it should be more relaxed.

But what troubles me about the discussion I sometimes hear from the tech side is that it resorts to easy tropes about deregulation and competition. I hear criticism of government from people who don’t vote or participate in the public sphere at all.

the 12% of SF that bothered to vote this week should be the only people allowed to complain about housing prices in the city.

— Sam Altman (@sama) June 5, 2014

Uber, Lyft and Airbnb have had to learn how to work with regulators over the last several years.

But now that more of Silicon Valley is venturing into increasingly regulated areas, the broader community needs to engage in both the public and private spheres.

In short, if you want to solve real-world problems, you have to live in the real world.