This post is not investment advice. Instead, it’s a meditation on the dynamics of the mobile gaming market in the context of an IPO which grants us raw data into a company in the space.

The company behind the wildly popular mobile game Candy Crush, King Digital Entertainment, is going public. An updated F-1 filing indicates that it wants to raise up to $532.8 million at a valuation of $7.6 billion. The flotation is no small event.

The company’s numbers paint a picture of extreme growth and extreme profitability: Its revenue expanded from $63.9 million in 2011, to $164.4 million in 2012, to $1.88 billion in 2013. During those three years, its monthly active user tally rose from 30 million in the first quarter of 2012 (that’s as far back as provided data goes), to 408 million in the last quarter of 2013.

At its IPO filing, King has three games among the top 10 grossing games, and nearly 75 percent of its total revenue comes from the mobile channel.

Big growth? Check. Proven model to monetize mobile? Check. And post-tax IFRS profits of $567.5 million in its most recent year? It’s almost unsurprising that the company has a “greenshoe” option to potentially sell even more shares in its public offering.

That’s the bullish case. However, I think that the company exhibits both the good and the troubling of the hits-driven mobile game world, or even the mobile app world, in which boom and bust cycles can lead to huge short-term revenue generation but uncertain long-term value. That uncertainty can make valuing application companies more tricky than other types of businesses.

King as a company has worked hard to ensure that it is not as top-heavy as it might be, a task that has proven incredibly difficult due to the sheer popularity of its signature title, Candy Crush. Growing a second game to its heights is something that I’m not sure that more than a very small handful of companies have pulled off.

The company addresses this in its S-1 (bolding: TechCrunch):

We believe the inherently social nature of our games, our data-driven marketing processes, our cross-platform technology infrastructure and massive player network are key competitive advantages. We obtain the vast majority of our installs organically or through viral channels that are driven by the effectiveness of our social features. We seed these channels by leveraging our significant capabilities in paid player acquisition. We run thousands of discrete campaigns every 24 hours, each with individual target metrics, and all subject to the same target return parameters. As of December 31, 2013, we had a massive network of 324 million monthly unique users and a track record of long-term retention driven by game longevity and our proven ability to cross-promote new games to our audience.

What the above means is that King uses its already popular titles to seed and grow other titles, accelerating their uptake in the market, and keeping the company’s mix of gaming titles fresh and its users happy — at least in theory. It’s a decent point, and the company appears confident in its ability to continue spinning this particular wheel.

In practice this means that the company’s largest titles — Candy Crush, for example — are its engines of user development. And if they obsolesce before new titles are nurtured, King’s ability to generate new titles of size becomes normal instead of super charged. Here we presume that the company’s model is practical, and repeatable.

So the health of the company’s major titles is quite tied to the long-term health of the company — yes, that is almost tautology.

How are the big games doing? Three titles essentially are King’s business: “In the fourth quarter of 2013, our top three games Candy Crush Saga, Pet Rescue Saga and Farm Heroes Saga accounted for 95% of our total gross bookings.” That’s according to the S-1 again, which then goes on to say the following: “Candy Crush Saga [accounted] for 78% of our total gross bookings.”

So, one game is more than three-quarters of its top line, and two other titles account for about 17 percent more combined.

This means that King has one mega-popular game, several moderate hits, and then dozens of small titles, or what it refers to in total as “180 game IPs.” From many, a few hits. If big titles are how King generates new hits, we can ascertain the chance of new hits being born by examining the health of Candy Crush itself.

(Aside: If Candy Crush’s revenues slip 10%, that alone would eliminate about half the revenue that its two other most profitable games generate. So, even a small slip in Crush land, and King loses the equivalent of a hit game’s top line. The scale here is, in relation, wildly vertical.)

Growth

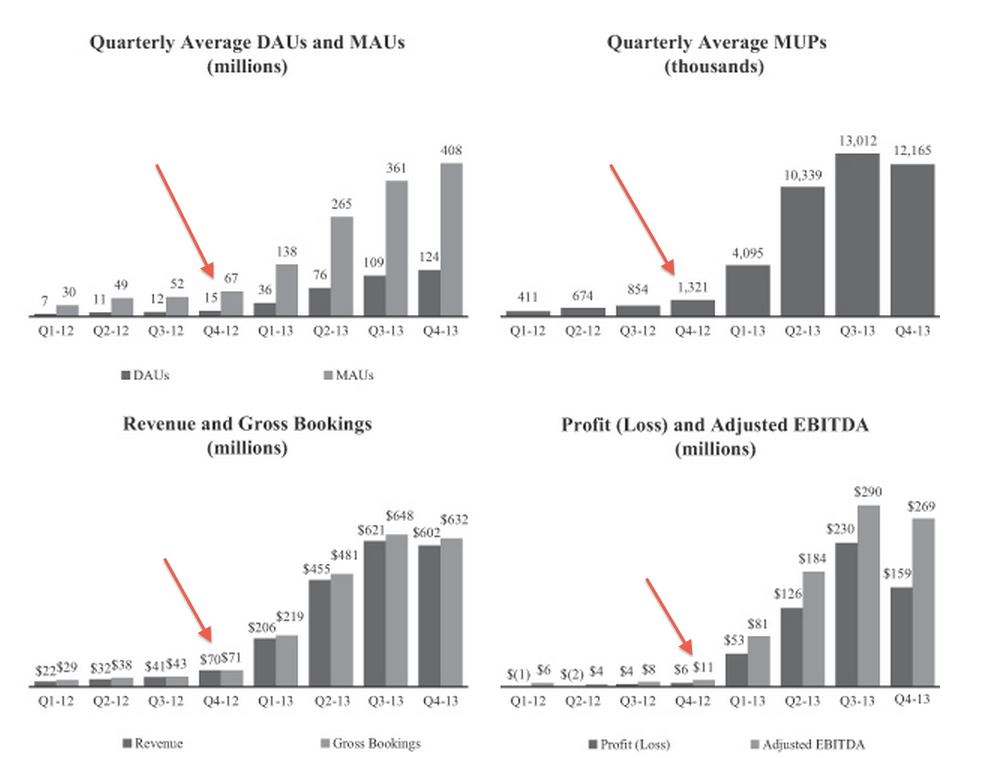

Between the third and fourth quarters of 2013, several key King metrics shrank, perhaps odd for a period noted for its high level of app usage due to the holidays. Quarterly average monthly unique payers (what King calls MUPs, or, in short, the unique number of people who bought stuff from the company’s games) fell, revenue and gross bookings both fell, as did the company’s profit in the quarter along with its adjusted EBITDA. What went up? Quarterly average daily and monthly active users.

So, while King managed to grow its audience in the quarter, its ability to monetize that audience fell.

Surprised by the negative quarter-on-quarter growth? The company says not to be, stating that “our recent annual revenue and gross bookings growth rates should not be considered indicative of our future performance.” The past is therefore not prelude, and if you were hoping for another year-over-year growth percentage that the company posted last year, you might want to temper your heat.

King expects Candy Crush to fall as a percentage of its total revenue in time: “In future periods, we expect Candy Crush Saga to represent a smaller percentage of our total mobile channel gross bookings as we diversify our mobile game portfolio.” But, the game remains important to the firm: “If the gross bookings of our top games, including Candy Crush Saga are lower than anticipated and we are unable to broaden our portfolio of games or increase gross bookings from those games, we will not be able to maintain or grow our revenue and our financial results could be adversely affected.” Right.

Let’s better frame how important Candy Crush has been for King’s growth. The company notes that the game was released on mobile in November of 2012. That means in the fourth quarter of 2012, King got a boost from a hit title. How big of a hit? Well, take a look at the below charts. I’ve added an arrow to each indicating the period in which Candy Crush was released on mobile devices:

That’s the sort of growth that dreams are made of. Returning to the question of revenue, what’s driving a decline in monthly unique paying users? King:

Average MUPs decreased by 0.9 million, or 7%, from 13 million in the quarter September 30, 2013 to 12 million in the quarter ended December 31, 2013. We believe the movement is as a result of less payment activity among occasional payers in our earlier Saga games, such as Bubble Witch Saga and Candy Crush Saga, in North America where we have enjoyed a rapid proliferation of network and payer growth. However, we have noted an increase in the number of payers playing in more than one game. These more engaged players are now driving an increase in average spend per paying player as discussed further below.

Given that Bubble Witch Saga records 2.1 percent of Candy Crush’s daily game play count (King data, a comparison of 23 million daily game plays for Bubble Witch, and 1.065 billion for Candy Crush), I believe that we can dismiss its revenue, and chalk up the decline in MUPs as indicative of a decline in payment volume at Candy Crush. Recall that our chart above framed how important the game was for King’s recent growth, and that it generates the lion’s share of its current top line.

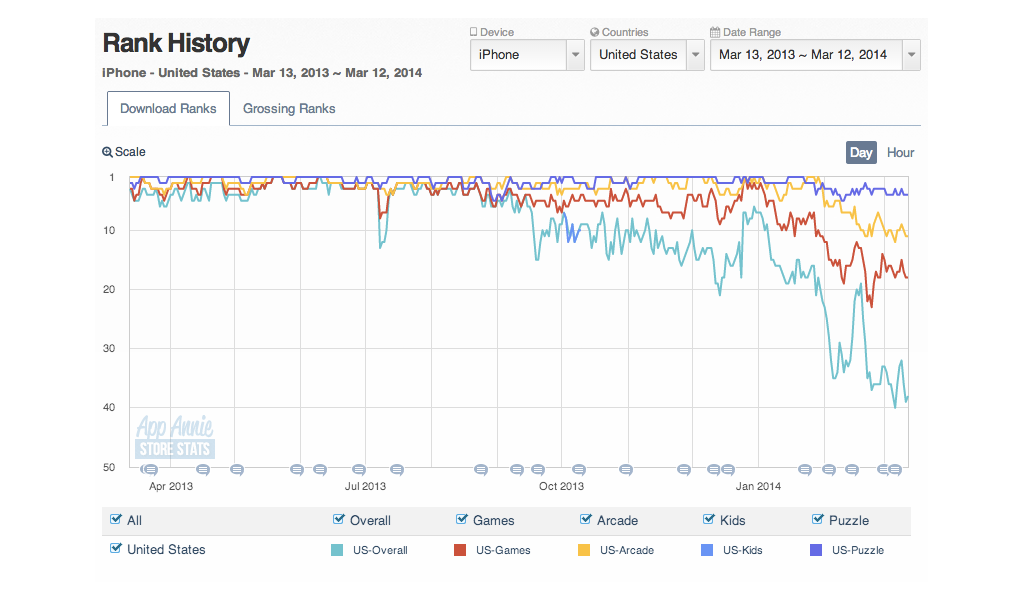

Is Candy Crush losing steam in the United States as the company hinted? It appears so. App Annie data indicates, for example, that Candy Crush on the iPhone in the U.S. has seen its download rates fall from the very top of the store’s rankings to more modest levels:

Still very respectable numbers, but numbers that are in decline.

So while King is seeing increases in its monthly and daily active users, it does appear that the beast that grew its financial metrics is aging. Hardly surprising given how long the game was on top, but something that could induce drag in King’s short-term growth. Let’s take a look at King’s other games to better understand what a decline in Candy Crush revenue could imply.

Potential

King’s growing MAU and DAU figures are encouraging. In the updated S-1 document the company filed, it supplied usage data for a number of its games — the top five most popular, essentially. The data covers two data points: December of last year and February of this year. So while King doesn’t provide any forward guidance in its filing, it does supply us with a snapshot of how its big games are performing.

For starting context: Candy Crush, from December of 2013 to February of 2014 saw its DAUs rise to 97 million from 93, but its total games played (daily average) fell from 1.085 billion to 1.065 billion.

To the rest:

Pet Rescue: December 2013: 15 million DAUs. February 2014 15 million DAUs.

Farm Heroes: December 2013: 8 million DAUs. February 2014: 20 million DAUs.

Papa Bear: December 2013: 5 million DAUs. February 2014: 5 million DAUs.

Bubble Witch: December 2013: 3 million DAUs. February 2014: 3 million DAUs.

So among the games large enough for King to break them out individually, one is growing quickly, one is mixed, and the rest are staying level in recent months.

Farm Heroes’ growth number is quite impressive, given that the game is now a full one-fifth as popular as Candy Crush. How much money does that mean it is bringing in? Recall that Farm Heroes was one of the three titles that comprised 95 percent of the firm’s gross bookings in the last quarter of 2013. Of that, Candy Crush was 78 percent, leaving 17 percent for Farm Heroes and Pet Rescue. (Caveat: I have heard from a person in the US that they saw a television ad for Farm Heroes, implying an extensive advertising budget for the game, which would help explain at least part of its quick growth.)

Comparing their fourth quarter 2013 numbers — for which the percentage data is relevant — and presuming that each title monetizes at the same rate per million daily active users — we can guesstimate that Farm Heroes drew in about 35 percent of the 17 percent slice that the two games comprised in aggregate during the three month period. Fourth-quarter bookings were $632 million. 35 percent of 17 percent of $632 million is $47 million. Now, we can amp that figure by using the game’s growth rate to summon what its first quarter (current year) top line will be. From 8 to 20 million DAUs, is an increase of 125 percent. That would peg first quarter revenue for Farm Heroes at $84.6 million. (Yes, there is an issue of using February results to predict full-quarter results, but let’s be conservative.)

So what does that mean? Well, the change between the fourth-quarter Farm Heroes top line that we have estimated, and the first-quarter number that we managed to extract from a rock is $47 million.

That $47 million is larger than the bookings decline that the company experienced in the fourth quarter of 2013 (sequential-quarter basis) by almost three times, and around double the seen decline in revenue for that period.

Thus, if our interpolations aren’t utterly bonkers, and everything else holds steady — keep in mind that Candy Crush is still seeing declines in games-played-per-day — King could see its revenue grow in the short term.

—

The above exercise helps us better understand the company’s potential trajectory. Here are a few sample caveats: Farm Heroes could monetize worse on a per million daily active user basis than Pet Rescue, meaning that we have grossly overestimated its figures. Other games could be seeing similar daily active numbers, but declining per-user revenue, meaning that other revenues could decline and wipe out our calculated coming gains from Farm Heroes. Candy Crush could have one bad month and spoil the soup. You see what I mean.

I think we can end with a question: How many more Farm Heroes does King have in the tank?