At the 2010 TechCrunch Disrupt San Francisco, Benchmark Capital Partner Matt Cohler took to the stage to talk about the state of the venture capital industry. In so doing, Cohler said that he thought too many investors were becoming focused on risk mitigation, which can often deter investors from going after companies that may be building something really big, trying to change the world — but will be slower to monetize and offer the requisite immediate ROI.

He then mentioned that he had recently led an investment in a company called ResearchGate, because when he asked the company’s founder, Ijad Madisch, what would constitute success in his mind, Madish replied, simply, “winning the Nobel Prize.”

“That sounds like aspiration and ambition to me,” Cohler said. And you have to give props to both the founder, for being so resolute in his goal, and to Cohler and the company’s other investors, for being willing to put money into a venture that certainly had no short-term plans to become a billion-dollar company. At the time, ResearchGate had just closed a series A round from investors like Accel Partners, Simon Levene, Bebo Co-founder Michael Birch, Joachim Schoss, Martin Sinner, Ulrich Essmann, Christian Vollmann and Rolf Christof Dienst.

What’s more, last week, ResearchGate closed its series B round, which was this time led by Founders Fund, with follow-on contribution from Benchmark Capital, Accel Partners, and Michael Birch, as well as Yammer CEO David Sacks. Again, true to form, Madisch is not revealing how much his company has raised, in either of its two rounds, because he doesn’t want the focus to be on the money. (Though both rounds were supposedly typical for series A and B, likely putting them in the range of $3-$5 million and $6-$8 million, respectively.)

As part of the series B round, Madisch told us that PayPal Co-founder and Founders Fund Partner Luke Nosek will both be joining Cohler on the startup’s board of directors. Madisch said that both investors had been long-time advisors to the company since he had initially visited Silicon Valley and had no idea what a “partner meeting” was.

So what is it about ResearchGate that has these investors thinking long-term impact, rather than short-term gain? The startup has been called a “Facebook for scientists,” which has increased poignancy given the fact that the founder tells us that he’s just hired a bunch of senior engineering staff from Germany’s Facebook equivalent, StudiVZ. (The company has headquarters in Germany, where Madisch is from, and Boston, and will soon be opening new offices in Silicon Valley for its staff of 75.)

Nonetheless, the founder explains that the Facebook for scientists is an oversimplification of what he and his team are up to, which is building a communication and crowdsourcing platform by which scientists can share their research and more.

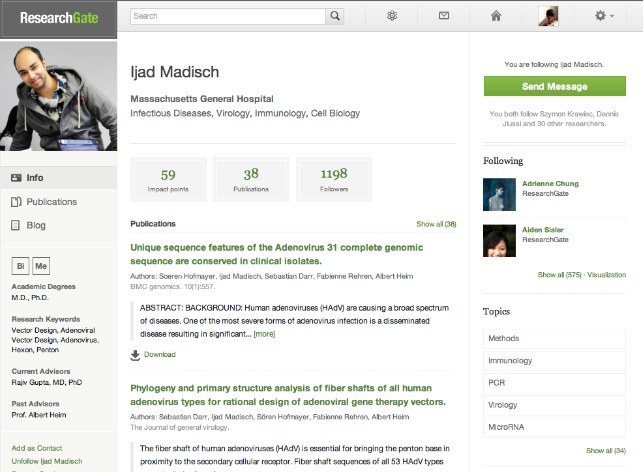

Madisch, who has a bachelor’s degree in computer science, a Harvard medical degree, a Ph.D in virology, knows what it means to be on either side of the medical world, as both physician and researcher — and how to code. He told us that, when it comes to medical research, academics study very specific problems, and if they want help with a particular study or test, they look for someone with a very specific skill and research set. That, in and of itself, is extremely difficult, as there are few public resources to enable quick discovery of those researching in similar niche fields. On top of that, searching for particular scientific papers that would lend insight into the particular problem — also not so easy.

Madisch told us that, as he went through his degrees and began studying and researching problems in virology, when a particular experiment didn’t work, for example, he would not share that with anyone, he wouldn’t write down the fact that, “hey, this virus isn’t growing on these cells, here’s why.” He said that he’s learned that this is typical of scientists and researchers, which leads to many experts simultaneously researching very similar, or related ideas to make the same mistakes, over and over again.

So, in short, the mission of ResearchGate has been to decrease research redundancy by creating a network in which scientists (of every stripe) can create a simple profile that contains information that would only be relevant to other scientists, like degrees, areas of focus, research keywords, advisors, publications, and so on. In turn, the team wants to give scientists a place where they can upload not only the journals they’ve published results in, but raw data, experiments that failed, etc., pooling those resources to make that knowledge and research accessible broadly, for free.

So far, nearly 1.5 million scientists from 192 countries have joined ResearchGate, which now contains 45 million abstracts, more than 10 million free, full-text PDFs on a diverse body of research, 15,000 job listings, and schedules for over 3,500 conferences. But, even so, the fact that scientists can upload additional data sets — beyond that which they’ve published in scientific journals — is huge, because, as Madisch says, records of research typically get lost or discarded, but now they can save it, upload it, and share it with others to help inform their research.

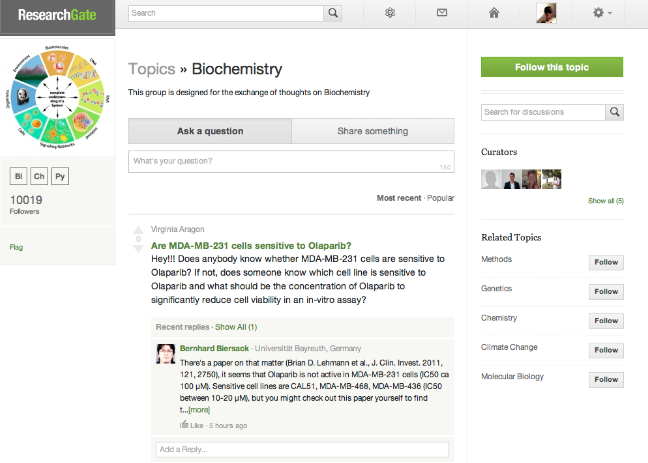

On top of that, ResearchGate offers scientists discussion topics and communities in which they can get answers from other specialists, help each other solve particular problems, whether it be coding PHP or investigating a polymer chain reaction. The idea is to increase interdisciplinary sharing of technical knowledge, enabling scientists to solve their problems faster. In addition, ResearchGate allows users to search through the largest scientific literature databases for articles and abstracts, as well as thousands of smaller open access databases, with the ability to bookmark and share those articles with colleagues.

In the big picture, Madisch is setting out to change the fundamental behavior of scientists and academics, who typically live mostly in the offline world, where they do research for 4 or 5 years, publish a paper, and raise funding based on what’s published. “Instead of having those 4 or 5 years exist offline, when scientists are gaining this incredible, specific technical knowledge that mostly goes unshared, I want them to have an online resource where they can use that knowledge to help other people,” the founder says.

Further provoking a potential change in the scientific community’s status quo, Madisch says the team has built out a reputation system (a la Klout), where users get a score based on their projects, how many questions they’ve answered, their activity within the community, etc.

“I want to change how scientists think about their data.” It’s a noble pursuit, and one that really could have global implications if it can achieve the kind of data-sharing and project collaboration that its platform aspires to create. But getting scientists to adopt and tend to reputation scores? That’s a tall order. No matter what kind of platform one builds, niche or not, it’s all about engagement, and with 20 percent of users logging in more than once a month, it’s going to take some time before the Nobel Prize is within their grasp.

But, there’s no doubt the investor belief is there. Says Founders Fund Partner Luke Nosek:

“We truly believe that the network has the potential to disrupt a much-outdated system, while leading the way in changing scientific discovery and the way research is disseminated.”

For more, check out ResearchGate at home here.