The European Commission is going after web companies over their failures to explain how their ad targeting systems work. But it’s not hitting the bulls-eye, because it’s confusing targeting with data protection, which are not quite the same issue.

The commission, for all of its good goals, has some clarifying to do. So does its big target, Facebook.

In a sensationalistic article today that claims “Facebook faces a crackdown on selling users’ secrets to advertisers,” The Telegraph reveals that it and the European Commission only sort of understand how Facebook works.

Commission vice president Viviane Reding proclaims that “I call on service providers – especially social media sites – to be more transparent about how they operate,” in a quote provided to the paper. “Users must know what data is collected and further processed (and) for what purposes.”

That’s a real issue, and something that Facebook could solve on its own.

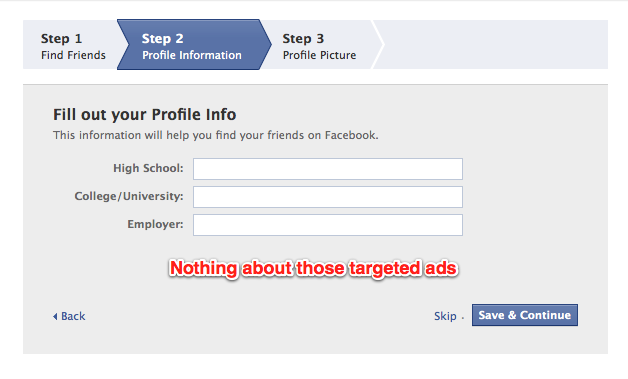

Two examples. A recent data information request by a dissatisfied Austrian user revealed hundreds of pages of data that Facebook had collected, that basically no one had known it was gathering. Another issue, which the The Telegraph alludes to, is that new users who sign up on Facebook don’t get any indication of how the company is going to be using the data they provide. Facebook instead leaves it up to them to figure out what’s going (presumably to avoid scaring anyone off before they get started).

But then Reding goes on to suggest that Facebook is not adequately protecting user data, which is off-base: “Consumers in Europe should see their data strongly protected, regardless of the EU country they live in and regardless of the country in which companies which process their personal data are established.”

The commission, the European Union’s executive body, is planning to issue a directive in January, instructing member states to implement laws requiring companies like Facebook not to show targeted ads unless users explicitly allow them to. That type of feature could undermine Facebook’s ad business model. And beyond any impact on Facebook, it could make the ads on the site a lot less valuable to users. Meanwhile, the commission’s data protection working group is meeting in December to examine Facebook and consider a closer privacy audit.

So let’s look at Facebook ads as they work today.

First of all, the company has to be paranoid about what it does with user data in order to maintain users’ trust in its service. Despite some missteps over the years, its ongoing popularity suggests a large amount of that trust is still there. If the company were to sell user data to third parties — which is how much of the online ad industry actually works — then people would get scared off from using the service. Just imagine if you started seeing ads related to your status updates and relationship situation in random banner ads around the web, without any indication of why you were seeing them. It would be disturbing. And, it’s not what’s happening now.

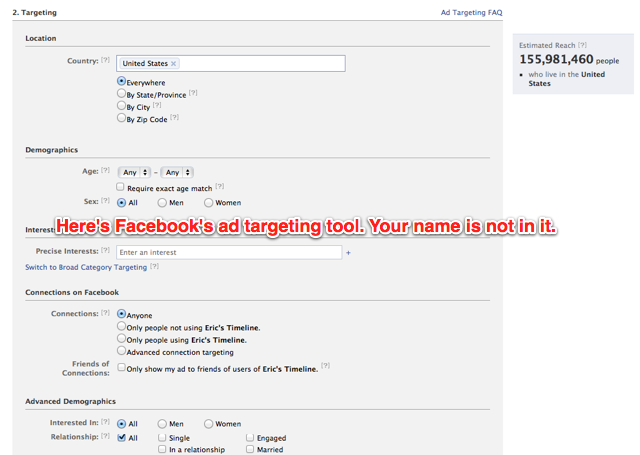

Instead, what Facebook does is let advertisers ask to target certain things about users via its ad creation tool, then it serves those ads to individuals on behalf of the advertisers. It is the middle man, anonymizing user data in order to protect individuals while still allowing advertisers to run ads that are relevant to users.

Facebook’s goal is to make the ads so relevant to people that they get a lot more value out of them than, say, a generic banner ad for an awful big-brand soft drink that most of us would never touch, anyway. If Facebook doesn’t target ads, then users won’t get value out of them, and advertisers won’t want to pay. Ultimately, it won’t just lose potential revenue, it might not be able to afford the costs of running and improving its service.

And when you think about Facebook’s style of targeted ads, look at what the company actually provides. The ads are basically an improved version of how traditional media advertising has worked for decades. Television companies survey users and sample some of their TV sets to figure out which type of people watch which type of programs. Then they sell ad space in those programs to advertisers who want to reach that demographic. Football fans don’t complain about targeting when an ad for beer comes on during a game, and most of them find it preferable to ads for the latest children’s toys. Facebook’s ads are a way for you to find out about a new type of beer from your favorite brewery, without ever having to see ads for toys.

The European Commission needs to explain how Facebook’s anonymized ad targeting system is not protecting user data. But, the commission is also right to push Facebook to better explain what’s going inside its ad-targeting black box.

The recent European user’s data request revealed that Facebook had been storing far more data than most anyone had expected, including a list of all of a given user’s log-ins with timestamps and IP addresses, deleted content, rejected friend requests, removed friends, and several unfilled data fields that could be for unreleased products. Facebook was also recently nailed for a bug that happened to track what users did around the web, a practice it has said it doesn’t do. The bug happened to surface at the same time as a patent filing describing a method for tracking users around the web. Combined with the lack of communication from Facebook to new users about how ads work, it’s understandable why there’s ongoing confusion about what how Facebook is collecting and using data.

It needs to update its data and ad policies (like this one) to explain everything it’s doing. And it needs to get more transparent with all of its users. For example, it could add a line to the sign-up flow mentioning that it will use data to power ad targeting, and linking to helpful docs that it has already created, like this one. Just a disclaimer could help its case with the European Commission.

And taking these steps wouldn’t just help it appease governments and media outlets — concerned users would be appreciate the moves, and reward the company with more of the trust it needs to succeed.