China may overtake Japan to become the world’s second-largest economy this year. On its heels is India, and countries such as Brazil and Russia are not far behind. What does this mean for entrepreneurs? That, increasingly, the big opportunities lie outside the U.S. Most people aren’t aware of another advantage in emerging markets: you can freely leverage the wealth of proven intellectual property that has already been created in developed economies. Most countries outside the U.S. and Europe lie in a Patent-Free Zone—where companies have not filed patents because they believe there is no market for their goods. So this intellectual property is available to anyone in those nations who can find a use for it.

China may overtake Japan to become the world’s second-largest economy this year. On its heels is India, and countries such as Brazil and Russia are not far behind. What does this mean for entrepreneurs? That, increasingly, the big opportunities lie outside the U.S. Most people aren’t aware of another advantage in emerging markets: you can freely leverage the wealth of proven intellectual property that has already been created in developed economies. Most countries outside the U.S. and Europe lie in a Patent-Free Zone—where companies have not filed patents because they believe there is no market for their goods. So this intellectual property is available to anyone in those nations who can find a use for it.

Take the iPhone as an example: it has over 1000 patents; yet Apple does not apply for patent protection in countries like Peru, Ghana, or Ecuador, or, for that matter, in most of the developing world. So entrepreneurs could use these patent filings to gain information to make an iPhone-like device that solves the unique problems of these countries. Apple has so far received 3287 U.S.-issued patents and has 1767 applications pending: a total of 5054 (for all of its products). Yet it has filed for only about 300 patents in China and has been issued 19. In India, it has filed only 38 patent applications and has received four patents. In Mexico it has filed for 109 and received 59 patents. So even India, China, and Mexico are wide-open fields.

Now consider diabetes technology. At the end of 2009, there were more than 12,070 patents issued or pending in the U.S. In Jordan there were only 36, and none were filed in most of Africa. Big pharma considers these markets either too small or too poor; it also hasn’t produced affordable drugs for the millions of desperate people who are increasingly suffering from disease in Africa and the developing world. But there is nothing stopping entrepreneurs from completing these tasks. The blueprints are readily available in the U.S. patent database.

JiNan Glasgow, a North Carolina–based patent attorney and CEO of NeoPatents, has been researching the global patent system and developing technologies to explore and map the patent databases. She found that only 5–10% of patents that are filed in the U.S. are actually used to provide commercial value. The rest go to waste.

JiNan Glasgow, a North Carolina–based patent attorney and CEO of NeoPatents, has been researching the global patent system and developing technologies to explore and map the patent databases. She found that only 5–10% of patents that are filed in the U.S. are actually used to provide commercial value. The rest go to waste.

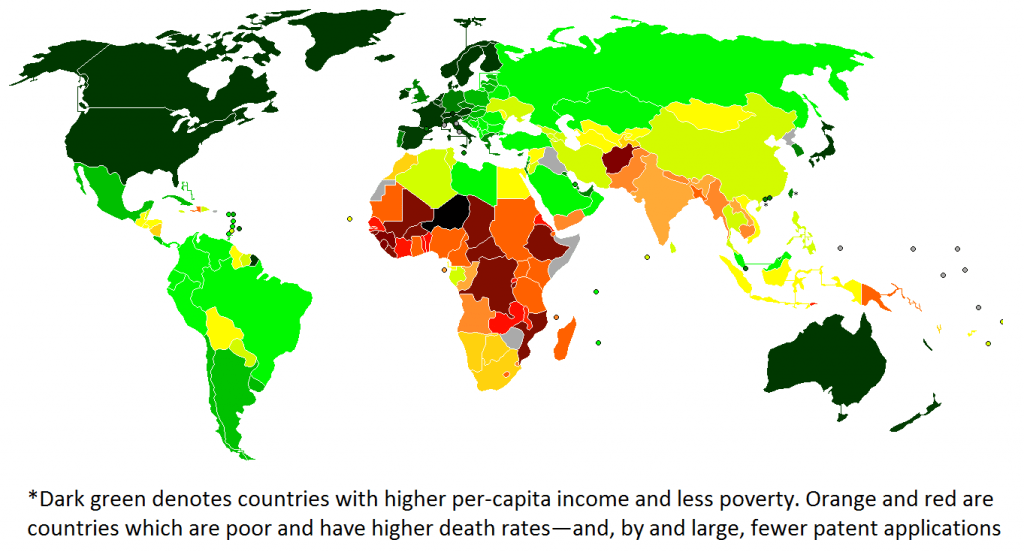

Glasgow also found that most U.S. companies have been ignoring emerging markets and not filing any patents there. When she compared the geography of patent filings with the UN Human Development Index, she noted a strong correlation: the richer the country, the greater the number of patents. This means that the wealth of the developed world’s intellectual property is freely available for use in the emerging regions, where patents are not filed. Glasgow called this the Patent-Free Zone—which covers most of the world, except for the U.S. and Western Europe. BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China) have only recently seen increases in patent filings—so all the patents filed in the U.S. over the past few decades are still within the free zone.

The way the patent system works is that when you have an idea that is new and unique and you want to protect it, you file a patent application with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). If the USPTO determines that you are indeed the original inventor, it grants a patent, a temporary monopoly that stops others from making, using, selling, offering for sale, or importing your invention in the U.S. for 20 years. But this is only in the U.S. To restrict people in other countries, you need to file a patent in that country, and to do so within one year of filing a U.S. patent. Most U.S. inventors don’t care, because they are focused on local markets. But multinationals do usually file patents in every country where they expect to do business. It is legal for anyone in the countries where patents aren’t filed to use these ideas. And this opens up big opportunities in those countries.

Take desalination, in which GE is one of the largest players. GE has spent more than $4.1 billion to acquire its part of the desalination business. Yet a decade after commencing, they’re still nowhere close to making desalination affordable and sustainable. GE’s progress depends on the patents it owns. As of 2009, GE invented 47 of the 832 U.S. patents in this field—just 5.6%, or a little more than one-twentieth. Consider the progress that GE could make if it could also use any of the patents that it doesn’t own—of which there are many.

How much better would the world be if we didn’t have to spend another ten years waiting for innovation in the desalination space? There are many areas of collaboration in the Patent-Free Zone that could produce innovative solutions for our world. Solar power, electric cars, mobile technologies for the poor, disease eradication, medical devices, food processing—to name a few. Wouldn’t it be ironic if poor countries ended up solving the problems of the rich? And I’ll ask my entrepreneur friends the same question I’ve asked before: What’s Better: Saving the World or Building Another Facebook app?

Editor’s note: Guest writer Vivek Wadhwa  is an entrepreneur turned academic. He is a Visiting Scholar at the School of Information at UC-Berkeley, Senior Research Associate at Harvard Law School and Director of Research at the Center for Entrepreneurship and Research Commercialization at Duke University. You can follow him on Twitter at @vwadhwa

is an entrepreneur turned academic. He is a Visiting Scholar at the School of Information at UC-Berkeley, Senior Research Associate at Harvard Law School and Director of Research at the Center for Entrepreneurship and Research Commercialization at Duke University. You can follow him on Twitter at @vwadhwa and find his research at www.wadhwa.com

and find his research at www.wadhwa.com .

.

Images: Women Barefoot Solar Engineers of Africa by Barefoot Photographers of Tilonia, Jerry Stifelman, and United Nations Human Development Index