“People in technology businesses are drawn to places known for diversity of thought and open-mindedness”, is what Professor Richard Florida concluded after studying the growth and success of 50 metropolitan areas in the U.S. The most successful regions were those with the most gays, bohemians, and immigrants. These groups flourish in Silicon Valley, and its diversity has undoubtedly provided it with great advantage. But after attending the recent Crunchies Awards, I realized that something important is still missing — women entrepreneurs. I was shocked that the only woman CEO on stage during the entire event was TechCrunch’s own Heather Harde. Nearly all the companies that competed in the event (other than the PR firms) had males at the helm. This dearth may be one of the reasons for which the Venture Capital community is in such sharp decline, and why the Valley isn’t achieving even more success.

“People in technology businesses are drawn to places known for diversity of thought and open-mindedness”, is what Professor Richard Florida concluded after studying the growth and success of 50 metropolitan areas in the U.S. The most successful regions were those with the most gays, bohemians, and immigrants. These groups flourish in Silicon Valley, and its diversity has undoubtedly provided it with great advantage. But after attending the recent Crunchies Awards, I realized that something important is still missing — women entrepreneurs. I was shocked that the only woman CEO on stage during the entire event was TechCrunch’s own Heather Harde. Nearly all the companies that competed in the event (other than the PR firms) had males at the helm. This dearth may be one of the reasons for which the Venture Capital community is in such sharp decline, and why the Valley isn’t achieving even more success.

An analysis of Dunn and Bradstreet data shows that of the 237,843 firms founded in 2004, only 19% had women as primary owners. And only 3% of tech firms and 1% of high-tech firms (as in Silicon Valley) were founded by women. Look at the executive teams of any of the Valley’s tech firms – minus a couple of exceptions like Padmasree Warrior of Cisco, you won’t find any women CTOs. Look at the management teams of companies like Apple – not even one woman. It’s the same with the VC firms – male dominated. You’ll find some CFOs and HR heads, but women VCs are a rare commodity in venture capital. And with the recent venture bloodbath, the proportion of women in the VC numbers is declining further. It’s no coincidence that only one of the 84 VCs on the 2009 TheFunded list of top VCs was a woman.

Is the background or motivation of women that prevents them from becoming entrepreneurs? I just completed a project with National Center for Women & Information Technology (NCWIT) to find out (Kauffman Foundation will be releasing our research paper this spring). Our analysis of 549 successful startups showed there was virtually no difference in motivation between men and women entrepreneurs. Just like men, women started companies because they wanted to build wealth, capitalize on business ideas they had, liked the startup company culture, and were tired of working for others and wanted to be their own boss.

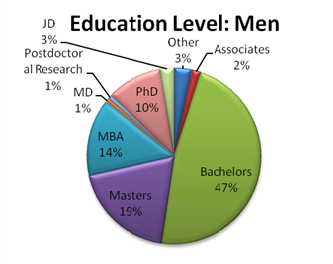

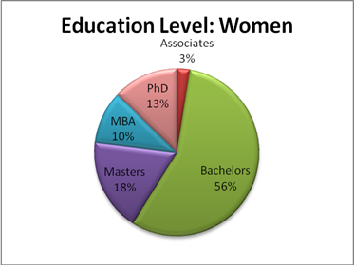

Women entrepreneurs were as highly educated as their male counterparts, had the same early interest in starting their own business, and learned the same valuable lessons from their work experience and from prior successes and failures. The only real difference was that women put a higher value on their business partners and on their personal and professional networks.

Women entrepreneurs were as highly educated as their male counterparts, had the same early interest in starting their own business, and learned the same valuable lessons from their work experience and from prior successes and failures. The only real difference was that women put a higher value on their business partners and on their personal and professional networks.

Is it that women are less competent than men? Quite to the contrary. An analysis performed by Cindy Padnos, managing director of Illuminate Ventures, showed that women are more capital-efficient than the norm and that venture-backed companies run by a woman had annual revenues that were 12 percent higher and used an average of one-third less committed capital. Women-led high-tech startups have lower failure rates than those led by men. And organizations that are the most inclusive of women in top management achieve 35% higher return on equity and 34% better total return to shareholders than do their peers.

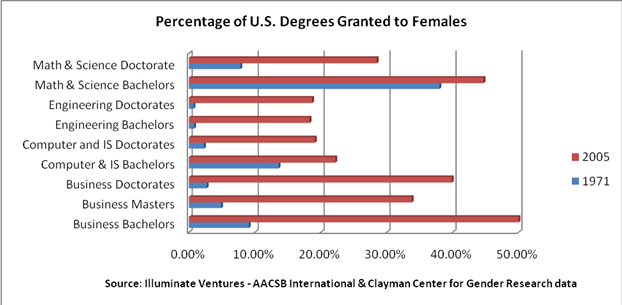

Padnos points out that the tide is turning in favor of women in education. Girls are now matching boys in mathematical achievement. In the U.S., 140 women enroll in higher education for every 100 men. Women earn more than 50 percent of all bachelor’s and master’s degrees, and nearly 50 percent of all doctorates. Women’s participation in business and MBA programs has grown more than five-fold since the 1970s, and the increase in the number of engineering degrees granted to women grew almost 10-fold.

Padnos points out that the tide is turning in favor of women in education. Girls are now matching boys in mathematical achievement. In the U.S., 140 women enroll in higher education for every 100 men. Women earn more than 50 percent of all bachelor’s and master’s degrees, and nearly 50 percent of all doctorates. Women’s participation in business and MBA programs has grown more than five-fold since the 1970s, and the increase in the number of engineering degrees granted to women grew almost 10-fold.

So what holds women back from starting companies? Shaherose Charania, of Women 2.0, thinks it is because women have had few role models and mentors. Additionally, it is harder for women to obtain funding than for men. She notes that historically, women-led companies have received less than 9% of venture capital investments; in 2007, the proportion of funded female CEOs dropped to 3%. And there is another problem which her group works hard to overcome: some old-time VCs won’t give women the time of day. Her group members recount examples of VCs and angel investors interrupting pitches to ask questions and make comments like:

- When are you planning to have kids?

- Why isn’t “he” the CEO?

- So you moved here because your husband lives here? What if he has to move for work one day? Will you go with him?

- You should cut your hair, dress a bit more manly if you want to be CEO.

Sharon Vosmek, CEO of venture accelerator Astia doesn’t think that VCs have an overt bias against women. Instead, it’s the way the venture-capital industry operates. Vosmek says that these “systematic or hidden biases” include:

- that VCs hold clear stereotypes of successful CEOs (they call it pattern recognition, but in other industries they call it profiling or stereotyping.) John Doerr publicly stated that his most successful investments – and the no-brainer pattern for future investments – were in founders who were white, male, under 30, nerds, with no social life who dropped out of Harvard or Stanford (2009 NVCA conference).

- VCs invest in people they know. If women aren’t in their natural networks, they won’t get through the door. We know that still today, men and women network in separate business networks.

- VCs want to invest in serial entrepreneurs. (This further reduces the chance for woman entrepreneurs.)

- The VC community is obviously male dominated, and it just got worse…after the cold freeze VCs experienced over the past 24 months, many women partners exited the industry. As the Diana Project research shows, a firm with women General Partners is more likely to invest in women entrepreneurs.

So, it is clear we have a problem here: we’re holding back the most productive half of our population. What can we do to fix this problem? NCWIT’s CEO, Lucinda Sanders, Shaherose Charania, Cindy Padnos, and Sharon Vosmek have all given me their suggestions. I also have some ideas of my own. I plan to write a follow-up post that details some of these, but I’d like to get your input first. After my recent BusinessWeek column on the dearth of women entrepreneurs, I was deluged with angry emails from men who disagreed with my conclusion that the problem isn’t a failure on the part of women but rather a societal failure. Some were really angry about my comparison of Wall Street firms to their counterparts in India. I’ve heard from the angry men, now I’d like to hear from the women. Please post your comments below.

Editor’s note: Guest writer Vivek Wadhwa is an entrepreneur turned academic. He is a Visiting Scholar at UC-Berkeley, Senior Research Associate at Harvard Law School and Director of Research at the Center for Entrepreneurship and Research Commercialization at Duke University. Follow him on Twitter at @vwadhwa.