Civil liberties advocates have long argued that “geofence” search warrants are unconstitutional for their ability to ensnare entirely innocent people who were nearby at the time a crime was committed. But errors in the geofence warrant applications that go before a judge can violate the privacy of vastly more people — in one case almost two miles away.

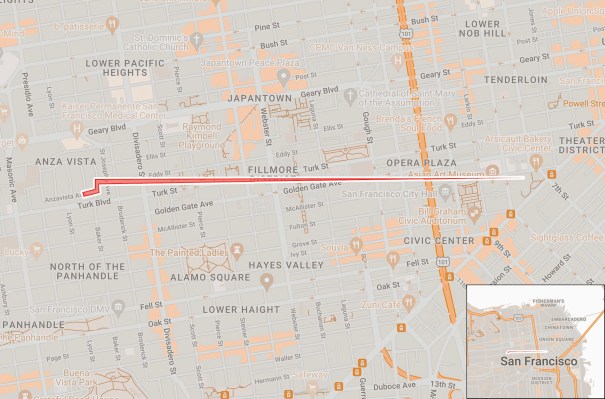

Attorneys at the ACLU of Northern California found what they called an “alarming error” in a geofence warrant application that “resulted in a warrant stretching nearly two miles across San Francisco.” The error, likely caused by a typo, allowed the requesting law enforcement agency to capture information on anyone who entered the stretch of San Francisco erroneously marked on the search warrant.

“Many private homes were also captured in the massive sweep,” wrote Jake Snow, ACLU staff attorney, in a blog post about the findings.

It’s not known which law enforcement agency requested the nearly two-mile-long geofence warrant, or for how long the warrant was in effect. The attorneys questioned how many other geofence warrant application mistakes had slipped through and resulted in the return of vastly more data in error.

Geofence warrants, also known as reverse location warrants, allow law enforcement agencies to seek a court order requesting data from tech companies that store vast amounts of location data on its users, like Google, to demand information on which devices were in a particular geographic area at a certain point in time, such as when and where a crime was carried out. Google revealed in 2021 that geofence warrants made up about one-quarter of all U.S. legal demands it received in the space of a few years.

The ACLU attorneys reviewed thousands of geofence warrants filed in San Francisco Criminal Court that were issued over three years between 2018 and mid-2021, which they say was likely only a fraction of geofence warrants used in San Francisco during that time. The attorneys warned that the reach of geofence warrants when surveilling in busy urban areas — San Francisco is one of the most densely populated U.S. cities — often include homes and apartment buildings, busy thoroughfares and places of worship.

The attorneys said they also found a geofence warrant that included four places of worship over a couple of streets in San Francisco’s Bret Harte neighborhood, allowing police to determine “where you were and who you were with” during the time that the warrant was in effect.

Another geofence warrant over a three-block area in downtown San Francisco captured anyone who was in the Le Méridien hotel or three nearby banks despite having no connection to the alleged criminal sought in the warrant. A review of the area by TechCrunch shows the geofence area also includes the headquarters of software giant Oracle and several busy pubs and restaurants.

“Whether you were in your hotel room or grabbing a salad at Mixt Greens on Commercial Street — with no connection at all to any criminal activity — your location information might well have been shared with the police,” ACLU’s Snow wrote.

The attorneys’ findings also showed the geofence warrants disproportionately targeted certain San Francisco neighborhoods more than others, particularly immigrant-heavy areas like Portola.

Google said in December it would begin storing users’ location data on their devices, effectively ending its ability to respond to geofence warrants going forward by forcing law enforcement agencies to seek the data directly from the device owners. Other tech companies that store troves of users’ location data — like Uber, Microsoft and Yahoo (which owns TechCrunch) — are known to receive geofence warrants.

Courts remain divided on whether geofence warrants comply with Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches and seizures, with an eventual legal challenge likely to end up before the U.S. Supreme Court.