The U.K.’s competition authority has fleshed out new details of how it plans to wield long anticipated powers, incoming under a reform bill that’s still in front of parliament, to proactively regulate digital giants with so-called strategic market status (SMS) — saying today that, in the first year of the regime coming into force, it expects to undertake 3-4 investigations of tech giants to determine if they meet the bar.

Of course the regulator isn’t naming any names as yet but it’s a fair guess that Apple and Google (aka Alphabet) will be towards the top of this investigation list.

The CMA previously found the pair’s gatekeeping of their respective mobile app stores creates substantial competition concerns. And, publishing a mobile market study on the duopoly back in December 2021, it wrote that its work “so far” suggests both would meet the incoming criteria for SMS designation for several of their ecosystem activities.

Tech giants that end up being subject to the U.K.’s special abuse regime can expect to face interventions that prevent them from preferencing their own products, the CMA also confirmed today.

Additionally, it said they may be required to provide competitors with greater access to “data and functionality” than their commercial interest might prefer. Interoperability could also be imposed on designated tech giants, the CMA suggested, as well as mandates that they trade on fairer terms. Algorithmic transparency could be another demand made of them by the new digital markets regulator.

The need to arm the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) with its own ex ante playbook to tackle the market muscle of Big Tech has been on the policymaking agenda in the U.K. for years. In November 2020 ministers confirmed their plan to set up a “pro-competition” regime targeting tech platforms with major market power with the goal of tackling some of the tipping seen in digital spaces, such as online advertising.

A key component of the plan for the new Digital Markets Unit (DMU), set up within the CMA, was that it would be empowered to tackle specific problems with bespoke interventions tailored to each platform. The reform also contained teeth, allowing for penalties of up to 10% of annual turnover for confirmed violations.

Three+ years ago, when the government first committed to the plan to tackle platform power, it looked pioneering. However the turmoil in U.K. politics of the past several years contributed to delaying progress on enacting the reform. As a consequence the U.K. has slipped behind peers like the European Union — which adopted its own flagship digital competition reform last year. The deadline for in-scope tech giants’ compliance with that regime is looming in early March.

Returning to the U.K., the domestic mood music changed again last April when the government, under prime minister Rishi Sunak, picked the ball back up and introduced the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill to parliament. Then, earlier this month, ministers wrote to the CMA asking it to set out a roadmap for implementing the future regime. Albeit, given the detail of the legislation remains under discussion by lawmakers, the ask was only for a “high level” plan.

The CMA’s response today takes the form of an overview that gives some steerage of what may be coming down the pipe for a handful of tech giants operating in the U.K. once the regime is up and running.

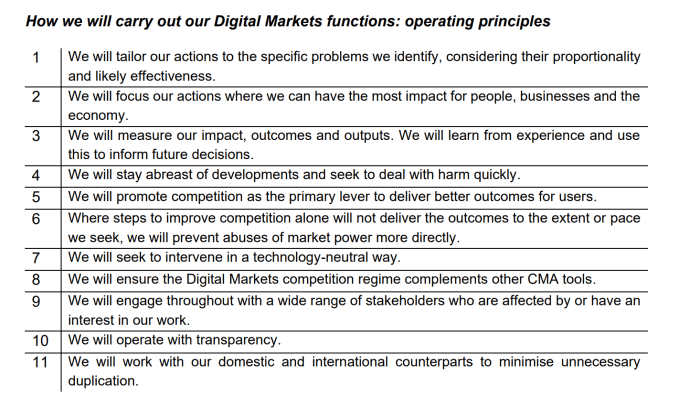

In the overview document, the regulator writes that the harms it will choose to focus on will be driven by a set of “prioritisation principles”. The text goes on to set out a list of 11 “operating principles” (see graphic below) it says will feed its decision-making on which of the myriad possible Big Tech abuse battles to pick — including saying it will have a focus on always applying a pro-competition lens; selecting for maximum impact; and seeking to move quickly (and repair harms, to coin a phrase) as issues develop.

“We will think broadly about consumer benefits,” the CMA also writes, fleshing out its thinking on principle 2 (aka impact). “As well as the price of goods and services (which in some digital markets is zero), consumers may also value choice, security, privacy, innovation, and their overall experience (for example, how much advertising they are exposed to).”

Image credits: CMA

A similar ex ante digital competition reform that came into force in the EU last year — aka, the Digital Markets Act — takes a more prescriptive approach to prohibitions and obligations, by literally setting out a list of ‘dos and don’ts’ for regulated giants. Six tech giants have been designated as so called “gatekeepers” under the bloc’s regime so far (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, ByteDance, Meta and Microsoft), for a total of 22 “core platform services” they provide, which range from adtech and operating systems to search engines and messaging platforms.

Some of the gatekeepers, including Apple, have filed legal challenges to the DMA designations. But the EU regime applies regardless in the meanwhile.

A German ex ante digital competition reform has also been operating since early 2021. This update has seen the country’s regulator designate a number of tech giants, including Amazon, Apple, Google and Meta, as subject to a special abuse control regime for firms deemed to have “paramount significance for competition across markets”. Other tech giants remain under market power probe there.

The German regime has clocked up the most mileage of the regional ex ante reboots so far. And the Federal Cartel Office (FCO) can point to some notable shifts it’s extracted from in-scope giants since then — including Google agreeing to reform its data terms; and offering not to inject publisher content it’s directly licensing into search results, which the regulator was concerned would amount to a self-preferencing risk which could harm rival publishers who weren’t licensing their content to Google.

Under the FCO’s watch, Meta also agreed to provide users with a way to refuse its cross-site tracking last summer, in a win for privacy driven via the perhaps unlikely avenue of competition reform. (Although the FCO has long been a pioneer at reading privacy exploitation as a competition abuse.)

What impact the U.K.’s equivalent reform might have in the coming years remains to be seen. The government still needs to get on and get it through parliament. So it’s not clear when exactly it might be operational.

For one thing there will need to be enough parliamentary time left before the U.K. General Election that’s expected later this year to pass the bill. Once the legislation is in place there may be an implementation period — plus the CMA/DMU will have to undertake investigations to designate SMSes. So the regime may still be years, plural, out from actually being able to exert pressure on Big Tech decisions.

In the meanwhile, the CMA’s overview offers some interesting hints of where the DMU’s hammer could fall in the coming years. And one overarching trend at least is clear: Big Tech is facing increasing curbs on its operational freedom.

That said, rising oversight of market-dominating web giants may be contributing to a strategic quasi-outsourcing biz dev tactic whereby Big Tech firms seek to invest in and partner with less tightly regulated startups that can be involved in activities which, if they were doing the stuff directly, could ruffle regulators’ feathers.

The links between cloud-computing infrastructure-owning Big Tech and generative AI startups look instructive here. Vast amounts of money and compute resource are being deployed in a way that threatens to enable current-gen tech giants to further extend their market dominance, via strategic tie-ups to startups operating at a claimed arm’s length distance from their own business empires, in spite of amped up competition oversight of their own core platform services. Microsoft-OpenAI anyone?