Over the eight years I’ve spent in VC, I’ve witnessed the consistently challenging vocabulary the industry creates. Venture capital is an industry full of big words, from technical acronyms to lofty descriptions. This often means we need to make more sense to founders, and that’s on us to use less jargon.

Historically, VCs are viewed as exclusive and cliquey, opposite from the “founder friendliness” that all VCs strive to have. While diversity and inclusion (D&I) has rightly become more of a focus across the ecosystem in recent years, the language we use needs to be noticed and still serves as a barrier to entry for founders.

We’re all guilty of tech-speak, and it’s usually accidental rather than malicious. But I believe it’s one of the biggest blockers to making our industry more accessible. While the misuse of jargon can keep outsiders out, it also plagues the inside of VC firms. A reliance on jargon also shows a lack of understanding and communication skills for VCs. High-performing investment teams will minimize their use of jargon and say what they mean to cut to the core of a founder and a business’s strengths and weaknesses.

It’s in everyone’s interests to upskill plain speaking. Being able to communicate ideas clearly and concisely is a core skill in any industry, but it’s one that VCs will struggle to foster in founders if they don’t lead by example.

Efficient jargon

Not all jargon is bad. When using it, ensure it’s used for the right reasons. It can be efficient. But at its worst, it can be a way that insiders keep outsiders at bay and perpetuate the VC industry’s elitist reputation.

High-performing investment teams will minimize their use of jargon and say what they mean to cut to the core of a founder and a business’s strengths and weaknesses.

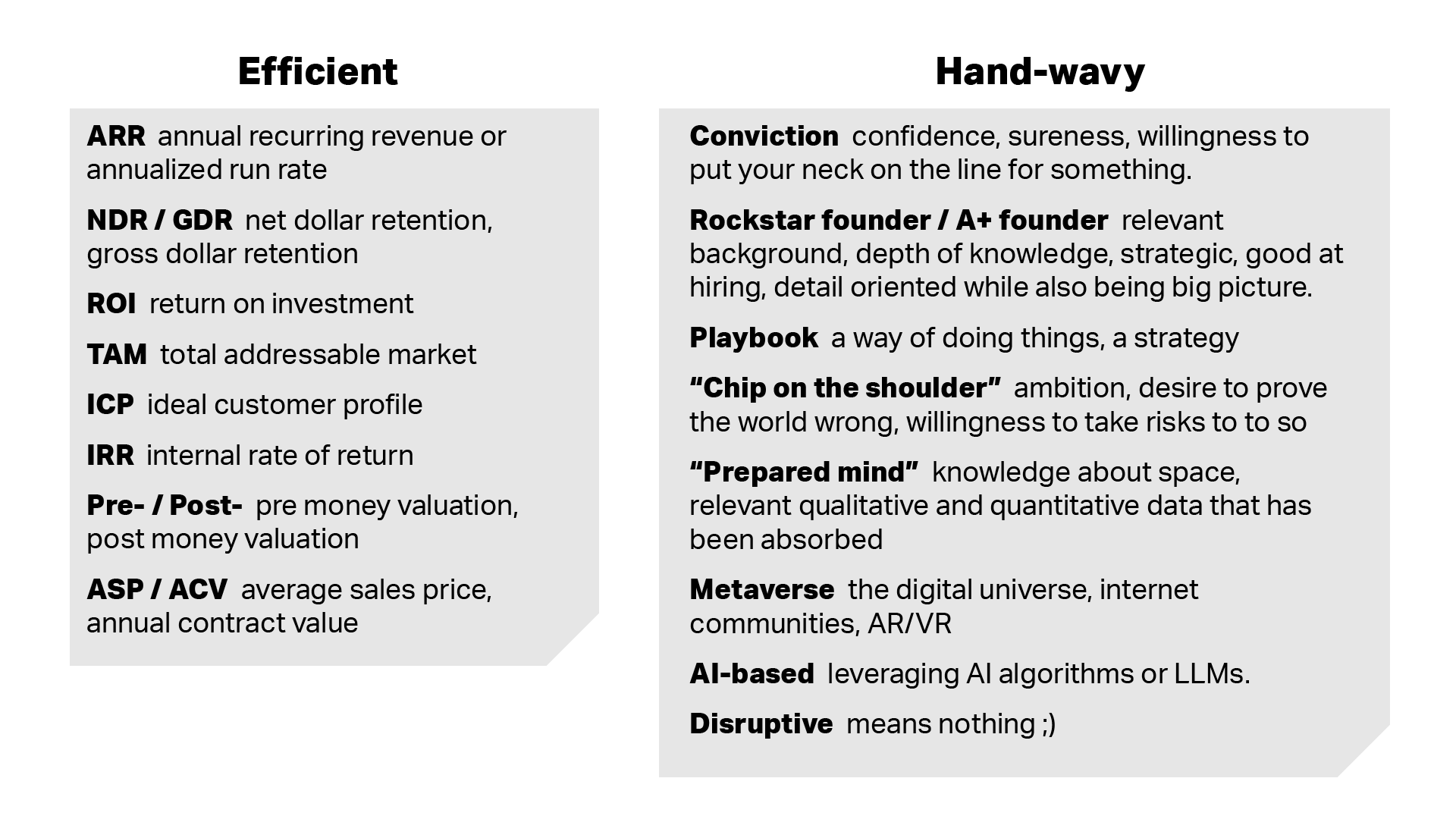

I see two types of jargon in the industry — efficient jargon and lazy jargon. “Efficient jargon” conveys common and crucial concepts that remove cumbersome repetition. These are often acronyms, like saying NDR instead of “net dollar retention.” Although these terms are effective in conveying ideas, they still place the burden on the listener to unpack the term.

For example, one wildly confusing yet completely fundamental metric is “ARR.” ARR can have two definitions, and it’s infrequent to hear anyone elaborate on which one they’re referring to:

- ARR — annual recurring revenue: The total contract value/number of years. This usage is the more accurate, original sense of ARR.

- ARR — annualized run rate: The monthly recurring revenue multiplied by 12. This metric is more commonly referred to nowadays but should only be relied on when a company has net negative churn.

- ARR — annual reoccurring revenue: This is an attempt to use jargon to make something that isn’t ARR seem like ARR.

ChartMogul has done a helpful breakdown of ARR in all its forms, which I would direct founders toward. However, communicating their original intent is more important than translating these terms. When a founder cuts through that jargon and clearly labels how they define “ARR,” it shows they have a fundamental understanding of what they are measuring and why it is essential. Sometimes, that is as simple as a statement: “We define ARR as monthly recurring revenue x 12.”

Founders are often experts in their fields — all sectors with their own acronyms and distinctive vocabularies. Just as we would encourage these entrepreneurs to convey their ideas simply and with clarity, we owe it to them to return the favor and ensure we are speaking to be understood. That’s not to say we should eliminate acronyms and shorthand, but we need to make a conscious effort to create a level playing field.

Lazy jargon

The second type of jargon is “hand-wavy” or “lazy” jargon, which I believe are tropes that VCs use to get out of actually thinking deeply about a person, company, or market. A few examples include:

- Instead of thinking deeply about why a market has potential, they say “huge tailwinds.”

- Instead of thinking critically about what elements of a founder’s pitch stood out and resulted in investment, they’ll put it down to the founder having “conviction.”

- Instead of articulating what makes a founder special, they say, “he’s a rockstar.”

The most common case is when a founder or another VC describes a company as, for example, “a next-generation platform leveraging generative AI to power the future of the metaverse.” And I will try to find a gentle way to ask what the company actually does.

In contrast, my favorite jargon-free way to hear what companies do is by starting with something like: “Imagine you’re an X. Every day, you have to Y, Z, . . . etc. In the past, you’d use A. With my product, you can do B instead. This is important because C.”

It’s not just founders who suffer from using lazy jargon; it’s also rife within the investor community. Someone might say, “This founder is a real rockstar, a total A+ player.” And I may find a way to ask what makes them better suited to their task than any other founder. I’d encourage others to be empowered to ask for clarity when faced with opaque and “hand-wavy” language.

The jargon of the first type has a role to play in simplifying communications, but only when there are practical and educational tools to ensure that everyone clearly understands what these more efficient terms mean. We also need to eliminate the second type of jargon as much as possible to add meaningful value to founders. When in doubt, define the terms when used.

The tech-speak epidemic

An over-reliance on jargon isn’t just a VC issue — a survey from LinkedIn and Duolingo found that 60% of workers said they had to work out corporate jargon independently. The same survey found that 40% of employees said they’d made a mistake at work because they misused or misinterpreted workplace jargon.

Using exclusive language reinforces the idea that there is a well-trodden path to being a successful founder on which you are taught this VC vocabulary. While the broader tech and finance industry should take action on this issue, it feels particularly prominent with venture capital, already viewed as a “closed” system in which background, education, or network matter too much. Speaking the “VC dictionary” means you must pick up from having the “right” training or “right” access. Ultimately, this undermines other positive efforts taken by VCs and financial institutions to improve diversity.

In addition, the geographic concentration of startup hubs like in the Bay Area makes this issue even more prominent in the VC world than elsewhere. Entering these hubs can sometimes feel like living in a foreign country where everyone but you speaks the language. Venture capitalists have a role to make people feel welcome and included in what can otherwise be a cliquey and closed environment.

Creating a fairer VC vocabulary, one word at a time

Much work must be done to make the VC world less opaque. Raising awareness of this issue is the first step to encouraging greater linguistic inclusion in the ecosystem.

There are websites and platforms out there that help provide greater transparency and are excellent tools for budding tech talent. Some blogs provide a glossary of the top 100+ VC terms, as well as a SaaS Glossary 101. Public Comps also has a great table of standard SaaS metrics, and Customerly has a useful page demystifying terms. For SaaS in particular, there is also the SaaS Academy, which provides training courses, free metrics, and templates for founders.

For a more extended read, I recommend the book “Venture Deals” by Brad Feld and Jason Mendelson, the founders and driving force behind the Foundry Group. Although originally published in 2011, it’s been continually updated to provide a comprehensive insight into how venture capital deals come together as the startup ecosystem evolves.

And to anyone feeling imposter syndrome, remember that jargon fluency is a test of access, not success.