OpenAI was never quite like other generative AI startups — or other startups period, for that matter. Its governance structure is unique and what ultimately led to the abrupt ousting of CEO Sam Altman on Friday.

Even after it transitioned from a nonprofit to a “capped-profit” company in 2019, OpenAI retained an unusual structure that laid out in no uncertain terms what investors could — and couldn’t — expect from the startup’s leadership.

For example, OpenAI backers’ returns are limited to 100x of a first-round investment. That means that if an investor puts in $1, for example, they’re capped to $100 in total returned profit.

OpenAI investors also agree — in theory, at least — to abide by the mission of the nonprofit guiding OpenAI’s commercial endeavors. That mission is to attain artificial general intelligence (AGI), or AI that can “outperform humans at most economically valuable work” — but not necessarily generating a profit while or after attaining it. Determining exactly when OpenAI has achieved AGI is at the board’s sole discretion, and this AGI — whatever form it takes — is exempted from the commercial licensing agreements OpenAI has in place with its current customers.

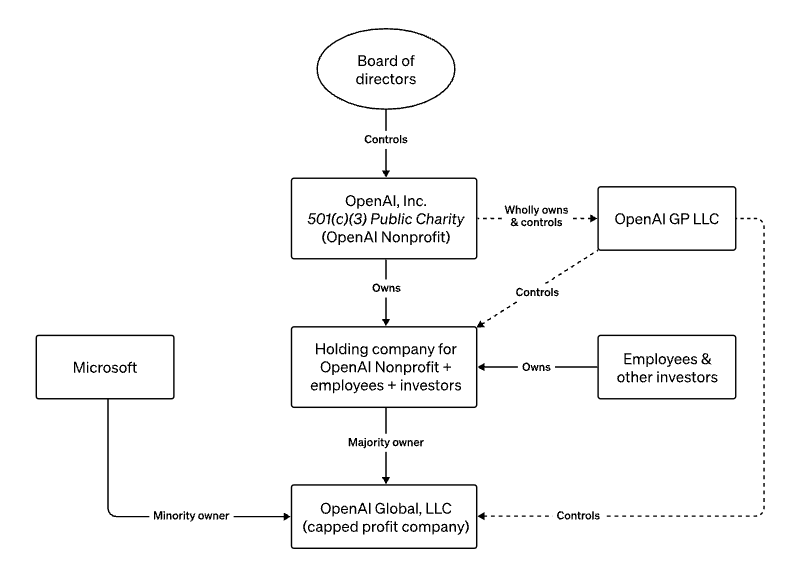

How OpenAI described its operating structure in the pre-turmoil days. Image Credits: OpenAI

OpenAI’s dual, mission-driven structure was aspirational, to say the least, inspired by effective altruism and intended to clearly delineate the company’s profit-making efforts from its more ambitious, humanistic goals. But investors didn’t count on the board exercising its power in the way it did. Neither did many employees, it seems.

The board was well within its right to fire Altman, who held a board seat but no equity in OpenAI besides a small investment through a Y Combinator fund. (Altman was the accelerator’s former president.) Certainly, investors couldn’t argue, as none had board seats. Until the departures of Altman and Greg Brockman, OpenAI’s former president and board chairman, the board was composed of three outside directors and three OpenAI executives, the remaining being Quora CEO Adam D’Angelo, OpenAI chief scientist Ilya Sutskever, tech entrepreneur Tasha McCauley, and Helen Toner, the director of strategy at Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology.

You might assume that investors will think twice about getting involved with such a governance structure going forward and treat the OpenAI fallout as a cautionary tale, and you wouldn’t be wrong. OpenAI’s backers are certainly displeased. Microsoft’s Satya Nadella was reportedly “furious” to learn of Altman’s departure “minutes” after it happened, and some key venture capital backers of OpenAI are said to be contemplating a lawsuit against the board.

TechCrunch+ spoke with several VCs and academics who predict that the knock-on effects will be both substantial and far-reaching.

Umesh Padval, partner at Thomvest Ventures, which invested in OpenAI rival Cohere, implied that OpenAI was structured such that “misalignment” between the nonprofit board and the rest of the company was almost inevitable.

“Akin to the model embraced by OpenAI, the board makeup can mirror that of for-profit entities,” he told TechCrunch+ via email. “However, the emphasis shifts toward ensuring that board members are not only highly experienced but also maintain a strong sense of independence. Although entities can strike a good balance with board members, without a clearly defined mission agreed upon by both founders and the board, as observed in recent events at OpenAI, it can lead to misalignment.”

Some investors may even rethink the “board model” entirely. “I am 100% pro-governance, but not always 100% pro-board . . . can we do better?” said Sheila Gulati, co-founder and managing director at Tola Capital. “What are the protections that investors who aren’t on the board can require and what of other stakeholders like employees? AI needs to be a harmonic combination of science and business. Researchers are the inventors and should as a group not be dismissed from leadership positions, including boards.”

I suspect the initial investors went along with [OpenAI’s] nonprofit structure to gain access to the investment opportunity. Jason Schloetzer

Added Christian Noske, a partner at NGP capital, on a slightly more measured note: “Most boards are unfortunately detracting value — as we’ve seen now in the situation with OpenAi. Nonstandard governance structures are always a concern for investors, but they’re being accepted in hot deals and market environments. Overall, OpenAI’s governance structure is not aligned with the nature of venture capital as we know it. At the same time, if we look at the other end of the spectrum, Robert Bosch is over 127 years old and has a somewhat similar governance structure to OpenAI — and it’s served them well. Savvy investors treat every business differently and know not to impose things on them.”

We asked Jason Schloetzer, an associate professor at Georgetown University’s McDonough School of Business (yes, the same Georgetown that pays Toner’s salary), whether what happened at OpenAI will shake confidence in researcher- or ethicist-led AI companies. Will investors want more commercial-oriented folks heading companies’ boards if they’re to invest?

Schloetzer doesn’t anticipate much will change in this department, positing that researchers and ethics experts will continue to sit next to capital providers to round out boardroom discussions. But he said he expects investors’ appetite for nonprofit-governance-associated risk specifically to diminish.

“I suspect the initial investors went along with [OpenAI’s] nonprofit structure to gain access to the investment opportunity,” Schloetzer said. “The thinking could’ve been that if these investments bore fruit — which they did beyond initial beliefs — the nonprofit structure would be able to flex or even completely change. That didn’t happen; the original board stuck to the original beliefs, which they have every right to do. And this is the result: A split between profit-oriented and mission and safety-oriented motivations. In the future, capital will flow to this kind of mission and safety-oriented motivation only if it believes in the mission and not if it believes the mission can eventually be changed.”

Could OpenAI sour investors’ opinions on boards altogether? Perhaps. Jo-Ellen Pozner, an associate professor of management at the Leavey School of Business at Santa Clara University, thinks so. And, she says, it’ll be to investors’ detriment.

“I think investors may become more wary of investing in firms with strong boards, which is really to their disadvantage,” she told TechCrunch+ in an email. “Boards of directors are in place to put a rein on managerial behavior. If it’s the case that Altman was preventing the board from enacting proper monitoring in pursuit of responsible AI development, it may have been right to shake things up, even if its implementation — from timing to stakeholder engagement to public messaging — was awful. If the lesson from OpenAI is that strong governance can destroy companies, we’re all in trouble; good companies need good governance to thrive and meaningful stakeholder responsibility can only be achieved through the determination of governance.”

Pozner struck somewhat of a hopeful tone, though, making the case that not all investors are pure profit maximizers or shareholder-value maximizers, and that these investors still want experts, researchers and ethics-minded players to run organizations.

“Investors with profit-maximizing motives will always want commercially minded folks with their hands on the wheel,” she said. “[But] good governance creates good business as a general rule, and perhaps even more so when so much is at stake.”

It might not be long before OpenAI puts that theory to the test.