News that Blue Apron is selling itself to Wonder Group — Marc Lore’s latest — for around $100 million marks the end of the former startup’s life as a public company.

Blue Apron raised a $135 million Series D back in 2015 for its meal kit business before going public in mid-2017 with a valuation of just under $1.9 billion. That figure had fallen to double-digit millions before Wonder agreed to buy it for $13 per share, cash. The transaction has an equity value of $103 million and represents a strong premium to the company’s preceding worth — some 77% more than its “30-day volume weighted average price” per a release, and 137% above its value as of the end of trading Thursday.

How Blue Apron got to where it is today is an interesting story, and one that we should trace from the company’s IPO through to today.

Rewinding the clock

At the time that Blue Apron went public, TechCrunch was impressed with its rising scale:

The company is showing a rather incredible amount of growth. Blue Apron said it generated nearly $800 million in revenue in 2016, up from $341 million in 2015. For the first quarter this year, Blue Apron said it generated $245 million in revenue, up from $172 million in the first quarter last year.

However, after targeting a $15 to $17 per-share IPO price range, the company later reduced its ambitions to $10 to $11 per share. Blue Apron sold stock in its debut for $10 per unit, and it barely defended that price point during its first day’s trading.

Why did the IPO fail to excite investors? Perhaps it was the massively tilted voting rights, which gave insiders 10 votes per share and offered new investors just one (the old Class A, Class B gambit!). Or maybe the key issue was slowing growth, which had dipped from 133% from 2015 to 2016 to just 42% in Q1 2017, compared to the year-ago period at the time. Profitability could have been a concern as well, with the company flipping from a small profit of around $3 million in Q1 2016 to a net loss of more than $52 million in the same period of 2017.

In fact, in the first quarter of 2017, Blue Apron posted more negative EBITDA than it did in all of 2016, and it managed to turn a roughly +$6 million operating cash flow result in the first three months of 2016 to –$19 million in the same quarter of the next year. In retrospect, the data is pretty rough-looking. Not that our coverage at the time was too warm:

[Blue Apron’s] financials, in addition to industry estimates, suggest that a large portion of Blue Apron’s subscribers cancel the service after testing it out. Without solid customer retention, it may be hard for Blue Apron to keep up its growth.

But there’s still a lot of untapped market opportunity. Everyone is a consumer of food, after all.

The bull and bear case, in a nutshell for the meal kit crew.

What happened next?

We need to fast-forward a bit as we do not have time to go over every year of Blue Apron’s financial life. So let’s pick up in early 2020, when Blue Apron reported its full-year 2019 results, which included:

- Net revenues of $454.9 million, down 32% from $667.6 million in 2018. That massive loss of revenue, however, was partially ameliorated by falling losses, which included the company posting a net loss of $61.1 million in 2019, down from $122.1 million in 2018.

Entering 2020, did the pandemic help the company? After all, with consumers at home, perhaps meal kits were a pandemic hit? Turning to 2020, 2021 and 2022 data:

- In 2020 Blue Apron generated revenues of $460.6 million, up about 1% from 2019. In short, no pandemic resuscitation was found that year. Certainly, stopping its revenue declines was a material achievement, but the company was still losing lots of money, including a net loss of $46.2 million in the year.

- In 2021, Blue Apron once again managed to grow, this time by 2% to $470.4 million in total revenues for the year. However, the company’s net loss nearly doubled to $88.4 million in the year, meaning that the company was still far from profitable. Indeed, even its adjusted EBITDA loss for 2021 came in at $39.2 million, far worse than the $1 million worth of adjusted losses it recorded in 2020.

In late 2021, Blue Apron managed to raise a chunk of capital. With some $73.5 million in its pocket, the company said at the time that it intended to use the funds for “working capital and general corporate purposes, including to accelerate its growth strategy to drive new customers and associated revenue growth” among other efforts.

How did that work out?

- In 2022 Blue Apron revenue shrank by 2% to $458.5 million, while the company’s losses soared. Blue Apron’s net loss reached $109.7 million in the year, even worse than what it saw in 2021. And its adjusted EBTIDA loss also ticked higher, to $79.3 million from less than half that the year before.

Clearly something had to change. So, Blue Apron got to work:

- In May, 2023 Blue Apron announced its intent to sell its operations to FreshRealm. FreshRealm makes ready-to-eat meals that are sold either under its own brand (Kitchen Table) or as a private-label solution for others. In short, they make food and sell it, and Blue Apron made food and sold it, and under the deal, FreshRealm would take on all the food prep work. The result of the transaction, apart from the deal’s financial worth, was that Blue Apron would become “asset light.” That’s business-speak for, “We’re going to have higher margins, just you wait!”

- The FreshRealm deal closed in June of this year, with Blue Apron receiving “approximately $25 million of upfront cash, subject to certain adjustments, and is eligible to receive up to $25 million of value upon the achievement of certain milestones.” The cash injection was no small deal for Blue Apron, as it allowed the company to rid itself of all debt.

- The deal was not free, however, at least in accounting terms. Blue Apron took a “non-cash loss on the FreshRealm transaction of $48.6 million” it told investors in its Q2 2023 earnings.

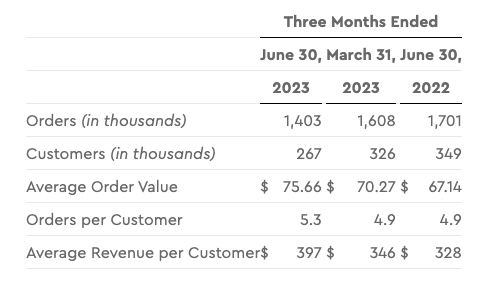

The question at the time, so far as we can parse from where we sit today, was what impact the shakeup in its operations would have on Blue Apron. It reported the following chart in its Q2 2023 results, which shows the decline that the company was fighting against:

Image Credits: Blue Apron

Blue Apron was getting by through driving more revenue from a shrinking customer base. That’s not an easy feat. Certainly, the company showed that it was able to boost its ARPC (average revenue per customer), but would that be enough? We may never really find out. After announcing a move to the Nasdaq earlier this month, the company has now sold itself for around $103 million.

So what went wrong? Blue Apron clearly caught magic in a bottle when it was in its early scaling phase. You can understand why venture backers were excited by the company: It was growing like mad and had what at least looked at the time like product-market fit. But consumer preferences can change, and it seems that Blue Apron never managed to truly turn itself around. Consumers drifted away, and despite better results from existing users over time, Blue Apron just didn’t make sense as a stand-alone company.

But that doesn’t mean that its 2023-era moves were mistakes. Consider if the company had not sold its operations, raising a good chunk of cash in the process. It would still have had debt on its books when it tried to sell. That would mean a greater enterprise value, making the deal more expensive.

Indeed, the ~$100 million price tag is an equity figure, which means it doesn’t take into account the fact that Blue Apron had $30 million in cash on its books at the end of Q2 2023. If we valued Blue Apron on an enterprise value basis in its sale, the figure would be decidedly less than $100 million. In short, the equity price tag is accurate, if not what we would consider the best method to value Blue Apron in its sale.

So the company did make some seemingly canny moves this year, lowering its operational complexity, raising cash, retiring debt, and overall looking a bit more balance-sheet fit than it had before. Provided that Wonder Group has a growth strategy, it may have picked up a useful asset at a price worth less than 0.25x its annualized Q2 2023 revenues. For a venture-backed company, that’s a poor multiple. Hell, for an airline that’s a poor multiple. But it does at least get Blue Apron out of its misery cycle and into the arms of the private markets where it might have a second shot at life.

The real lesson in all of this is that selling to consumers is hard. That selling lower-margin goods to consumers is harder. And that building a venture-backed business off dinner prep in a manner that involves a physical footprint and tricky shipping and a material cost to acquire customers is perhaps not the winning move.