Over the last couple of months, I’ve spoken to a number of early-stage investors — both angels and VCs — who seem to be proud that they’ve been able to take 25% to 30% of a startup’s equity in an early-stage funding round. In one case, an angel investor patted themselves on the back for “managing to convince the founder to give them a 41% stake.” I was reminded of that several times as I was in Oslo this week, speaking with a number of players across the startup ecosystem.

If you are reading the above and wish that you, too, could command that level of ownership in a startup, I’ve got some advice for you: You are being short-sighted and are hindering the startup, the founders and your own chances of finding success.

Running a startup is hard. That means investors should help, not set up a situation in which the founders of a startup are disincentivized and demoralized, and won’t be appropriately compensated for their hard work in the case of an exit. That’s precisely what will happen if investors take too much of a startup, too early.

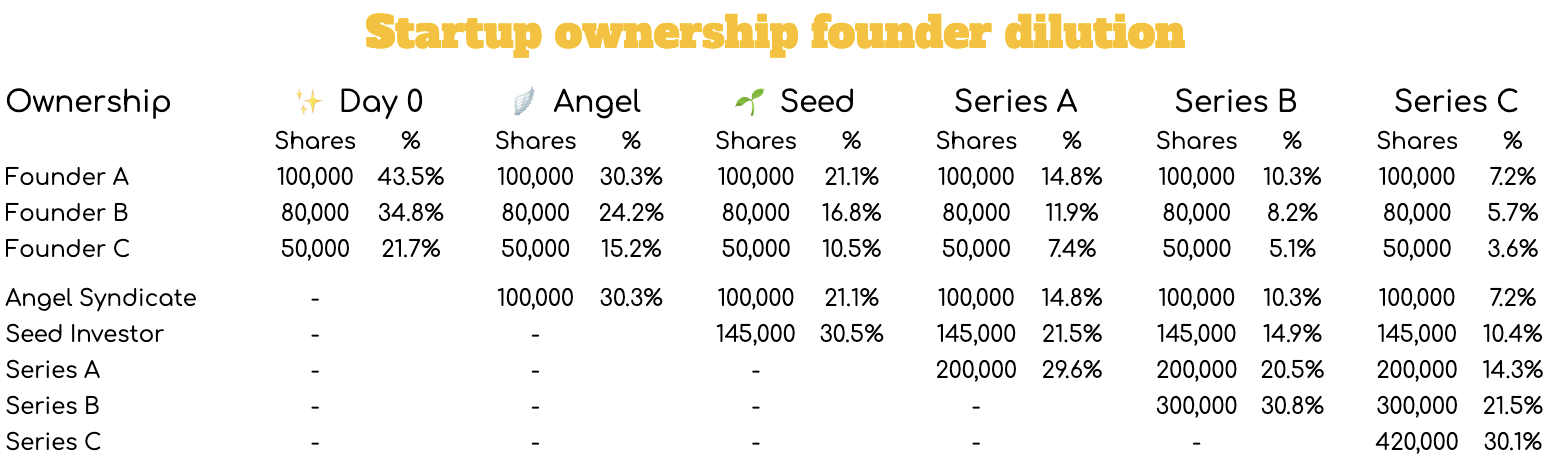

To explain why investors patting themselves on the back in early rounds are slipping a poison pill into the startups’ cap tables, let’s take a look at what would happen to a company that dilutes by 30% in every funding round.

Why “poison pill”? Because diluting founders too much virtually guarantees that the company won’t yield a significant return on investment; if it needs to raise additional funding further down the line, future investors will likely balk at how little ownership is left for the founders.

Investors always say they want to invest in the next Mark Zuckerberg, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, or Reed Hastings. Well, the Facebook, Google and Netflix founders owned 21%, 31% and 24% of their companies, respectively.

Not all founders do that, though. When Twitter eventually went public, the founders owned only 7% of the stock, but learning from his experience, Jack Dorsey went on to found Square and made sure he hung on to 24.4% of the company’s equity.

The disparate percentages make a huge difference. When Twitter went public, Jack Dorsey had a 4.9% stake in the company. Given that it had a $24 billion market cap at IPO, that would have net him a hell of a payday. That’s not too bad, but it pales in comparison to what the (far smaller) Square IPO managed later.

Square’s last round of funding before its IPO was a Series E; that’s at least five rounds of investment. Still, at IPO, it was valued at around $2.9 billion, and Dorsey’s 24.4% was worth $700 million or so.

“But, Haje, Dorsey got $1.1 billion from Twitter, and ‘only’ $700 million from Square,” you might argue. Yes, but Twitter took almost 14 years to get there and Square did it in half that time.

Sammy Abdullah, founder and managing partner of Blossom Street Ventures, did the research to see how much equity founders of some big-name IPOs had when the companies went public; it’s a reasonable benchmark.

Overall, Abdullah’s data shows that the median level of founder ownership at IPO is 15% and the average is 20%.

Great founders know that equity is extremely valuable — it’s the single most valuable asset in a business, in fact. Put simply, founders who allow themselves to be diluted too much by early-stage investors aren’t great founders.

Let’s continue with this exercise. This is what it would look like if every round diluted the founders’ stake by 30%:

Mapping out founder dilution over time. Image Credits: Haje Kamps / TechCrunch

As you can see, founder ownership can hit the single digits by Series C. If this company raises through a Series E, well, you can imagine the founding team would be left with barely enough to bother.

If you push founders to accept the sale of 30% of their equity early in their startup’s life, you may be setting yourself up for greater profits in the short-term, but you’re effectively limiting how many rounds of funding the company can raise before the founders are diluted down to a meaningless amount. And, since later investors will consider that dilution, too, it makes sense that being less greedy up front is the more viable path to greater returns.

There’s more than just investor sentiment and signaling to consider. If their ownership dwindles too far, it’s only a matter of time before the founders wake up one day and think, “You know, the opportunity cost for continuing this project is too high. I may as well wrap it up, start a new company and get it right this time.”

Early-stage investors can do a lot of damage to the long-term viability of a company. Folks, you’re not in the get-rich-quick game, so act accordingly and set yourself up for long-term success.