With Y Combinator Demo Day upon us, ’tis the season of $2 million on $20 million cap SAFEs. While many investors have been vocal against such raises, YC partners generally stand by them and even YC founder Paul Graham is vocal with his defense.

As a longtime seed investor, I’ve seen many founders make fundraising decisions without realizing the long-term impacts on their companies. With a number of seed investor models out there, it’s important for founders to understand the underlying incentives and biases of different investor archetypes, ranging from YC to seed firms to multistage firms.

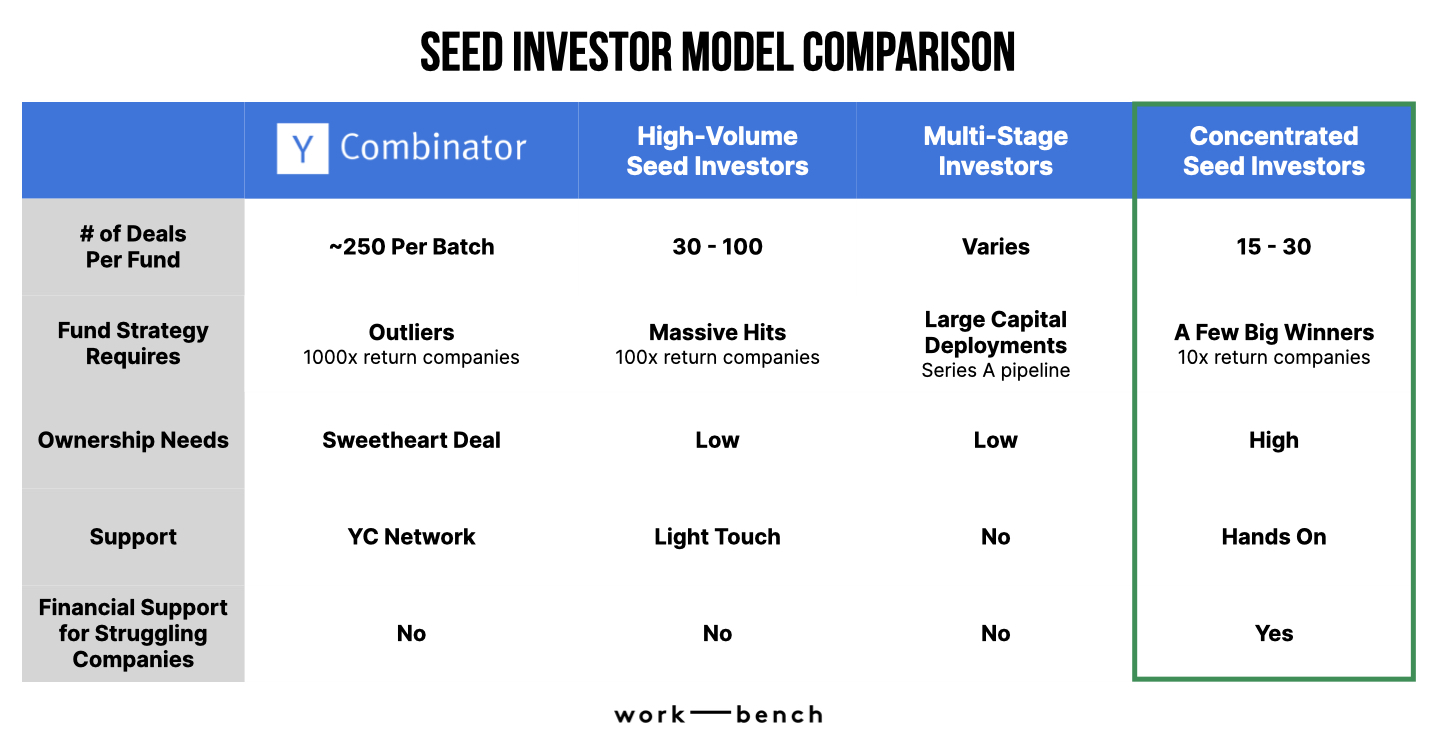

To summarize my takeaways, I created the following table, which I walk through in greater detail below:

Seed investor model comparison. Image Credits: Work-Bench

Y Combinator

There’s no debating that in aggregate, YC is a strong credential for founders in their earliest days, and they have a great crop of winners. The question for early-stage founders becomes, “What’s the hidden cost of fundraising from YC, and is the benefit evenly distributed?”

Companies that secure a spot in a YC batch not only receive a stamp of approval, but also gain access to a high-quality network of peers and alumni to learn from. In exchange, YC gets a sweetheart deal, investing $125,000 for 7% of the company and then an MFN (Most Favored Nation) letting them invest $375,000 in the future at favorable terms.

What’s important to understand is that YC’s goal is around finding and investing in extreme outliers.

YC’s own Garry Tan recently shared that “we only make money when the company becomes huge and is actually valuable. Like Coinbase or Airbnb or DoorDash.” On the flip side, what happens to companies that aren’t rocket ships, especially in a post-ZIRP (zero interest rate policy) environment?

The answer is that they’re out of luck: The YC model is “survival of the fittest,” and struggling companies are likely to go extinct. While this strategy has proven successful for their financial model, it certainly influences how they advise and support companies.

Pricing too high at an early stage is rife with issues that can plague the company’s growth if it doesn’t operate to perfection.

Raising a $2 million SAFE at a $20 million cap, whether because of a YC partner’s advice or peer-induced fear of missing out (FOMO) from batchmates, limits the type of investor you can pitch (whether the company realizes it or not) and raises the bar for the milestones needed to raise a Series A.

Given that most Series A investors would look to at least 2x the valuation of the seed raise, consider the milestones that would be sought out in a scenario to justify a $20 million valuation doubling to $40 million, compared to a $12 million doubling to $24 million.

More so, when raising a $2 million on $20 million round, startups’ cap tables typically become populated with angel investors and two to three high-volume seed funds along with YC, and if they hit any snags in their journey, there’s no additional financial support for them.

High-volume seed firms

High-volume seed firms invest in 30 to 100 deals per fund, and given that they look for returns in a handful of massive hits, they’re more focused on achieving a higher surface area of company coverage in a particular sector, geography, or other strategy than on optimizing ownership in any particular company. This leads them to invest with low, or even no, ownership requirements.

The nature of partnering with a high-volume seed firm is that their strategy provides limited hands-on resources for portfolio company support. Given their exposure to so many startups, these firms often focus on community and content initiatives. In this regard, they actively connect portfolio company founders and executives to crowdsource tactical guidance.

In this model, portfolio companies get occasional time with partners who work with a large number of early-stage companies. So, if a common question around hiring or scaling comes up, they see so much that they’ll usually have a helpful point of view or a founder who went through a similar situation to point to.

The issue here is that given the limited bandwidth partners can provide, when companies run into an inevitable challenge that’s unique to their situation or that requires specialized knowledge outside of the partners’ background/core expertise, they’re left to fend for themselves. Additionally, because this fund model focuses on making high-volume investments and then putting additional capital into some of the breakout winners, there are limited financial resources to support struggling or less-than-skyrocketing portfolio companies.

Multistage firms

Especially in this environment, it’s been popular for multistage Silicon Valley firms who typically invest at Series A and B to dabble in seed rounds. During the reset of 2022, seed-stage investments were perceived as a safe haven (given the relatively smaller check sizes) while they licked their wounds after overdeploying capital in 2021. While raising from a multistage firm seems like a high upside move, there’s a lot of inherent risk in working with them at seed versus waiting until Series A.

On the positive side, raising from a multistage firm gives seed startups great brand clout, a large seed check, and a high valuation. These factors can collectively be a net positive if the startup’s metrics and performance demonstrate rapid growth sufficient for a large Series A at good terms.

However, while multistage firms often tout seed-stage investments as being important and getting full support of their firm, in reality they get limited time with their partner and limited access to broader firm resources. It’s just too small a check relative to their fund size, and too early a company stage to align with what support they can or will offer.

The most important point to be aware of with multistage firms is that seed-stage investments are just an option call for them. Raising a seed round at a high valuation implies much higher milestones across ARR, customers, and general business progress in order to raise a Series A, and if a company doesn’t perform at astronomical levels, they’ll leave the company out to dry. It’s hard for companies to bounce back from the negative signal of a multistage investor backing away paired with not achieving breakout metrics to raise.

Concentrated seed firms

Last but not least, concentrated seed firms take a high-conviction view of investing, often digging deep into hyper-focused geographies, specialized sectors, and/or thesis-driven approaches. Given these firms only make 15 to 30 deals per fund, they bet on each investment making a meaningful return.

Technically this capital is more expensive than the other options above, given that concentrated seed firms require high ownership, often between 15% and 20% (implying lower valuations), and pro rata rights in order to continue investing in their winners to generate strong returns for LPs. So YC companies raising $2 million on $20 million rounds is a nonstarter for them.

While faced with more net dilution, the trade-off is that founders receive significantly more hands-on support throughout their scaling process given there is a reputational and financial impact hanging on each companies’ success. Concentrated seed firms offer support ranging from recruiting services, go-to-market counseling, technical support to aid product development, and more. For first-time founders, this added support can be a game changer in the survival of their company. Even for multi-time founders, the added boost of early support can help them achieve more milestones in a shorter amount of time.

Additionally, concentrated seed firms help garner additional capital beyond the seed round. This can take the shape of providing financial support to struggling companies that need extended runway, supporting the raise of a seed extension round, or taking a hands-on approach in helping secure a Series A raise — between assisting to craft the narrative, creating and reviewing collateral, and making targeted VC intros.

All in all, each firm archetype offers its own constraints, biases, and benefits. It’s important for founders to be aware of each so they can vet and select the best investor for their “decade-long marriage.”

I may be biased as a general partner at a firm that employs a concentrated seed approach, but I’d strongly recommend not raising a $2 million SAFE on a $20 million cap. Pricing too high at such an early stage is rife with issues that can plague the company’s growth if it doesn’t operate to perfection. As explained above, it scares away investors who can be most impactful during the inherently riskiest periods of a company’s life.

My advice is to trade an incremental amount of dilution for the opportunity to work with a concentrated seed specialist with a hands-on support model who can help amplify early efforts. However, it’s crucial for a concentrated seed firm to have specific and deep domain expertise that aligns with a startup’s focus. This will ensure the investor is able to provide the most relevant support as well as understanding the proper KPIs to measure the business’ health. Founders can determine this fit by doing their own due diligence and asking:

- Did this investor show a knowledge of my market and ask thoughtful questions?

- Are they interested in and excited about my category?

- Did they understand the differentiations between me and my competitors?

- What milestones are they looking for in order to lead my seed?