Merely weeks after emerging as the apparent heir to address social media’s woes and generating over 100 million users in less than five days, Threads appears to be, well, fraying at the edges already with a recently reported 80% drop in daily active users since launch.

Just recently, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg announced that Threads would be introducing “retention hooks” to keep users on the platform after nearly half of them left in the weeks following its launch. The platform — celebrated early on for its “combination of the ridiculous, the lighthearted, and a little cringe” — has quickly become another example of the expeditious cycle by which innovation in social media operates and burns out users.

Since the Big 3 — Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter — first emerged in the early aughts and set the precedent for social media, they have reigned over our lives and culture. Consumers have been essentially conditioned into an anticipatory state — always wanting while waiting for the next greatest thing in social media.

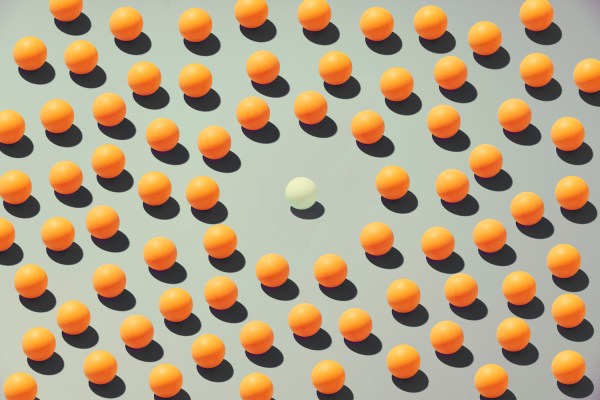

From Clubhouse to Bluesky and now Threads, most new platforms have at some point been designated the vestibule by which social connection and digital community will carry on, only to be thwarted by controversies, content moderation issues, dwindling engagement, and more. Only a month after launch, Threads users are already lamenting over platform burnout.

The hard truth behind the phenomenon? For too long, social media platforms have been operating as if connectivity provides the same fulfillment as human connection. The result is, two decades later, social media’s driven our culture and communal well-being to an unprecedented loneliness epidemic that no platform seems capable of fixing, let alone addressing. It’s time for a hard reset.

In an age where social isolation and loneliness are at an all-time high, perhaps we stop treating connectivity as a substitute and focus on facilitating true, meaningful connections.

The early days of social media were the golden days

The early days of social media didn’t just impress tech investors and solution builders; they galvanized us all with a childlike wonder — asking us to imagine how the other side of the world could be a single swipe away; how we might reconnect with childhood friends and meet strangers who would become lifelong ones; and how location and proximity to others would have no bearing on our ability to forge relationships.

For too long, social media platforms have been operating as if connectivity provides the same fulfillment as human connection.

Facebook’s (“connect and share”), Twitter’s (“create and share”), and Instagram’s (“capture and share”) original missions, above all else, signaled the potential to build a more connected world, and one that we were each encouraged to partake in.

But in recent years, social platforms have evolved away from their early models to find new revenue streams and expand their audiences, leaving users with new things to do and consume, instead of people to connect with.

Rather than forging or maintaining relationships as they set out to do, social media platforms became focused on becoming the “global town square” — not just of communication and connection, but also of consumption via e-commerce and shared knowledge fueled by social echo chambers. First came Facebook’s Marketplace feature, then Instagram’s controversial Shop tab. And amid rising social discord, it seemed that the never-ending volume of ads was only to be matched by the amount of increasingly pious and political declarations.

Overnight, we began nourishing our brains with seemingly endless timelines of information and developing a dependency on social platforms that reduced our dependency on the communities around us. It’s no wonder we’re facing a loneliness epidemic.

Social media: A vestibule of connection or loneliness?

Social connection has been on the decline for decades — but now it seems to be in crisis.

In May, the U.S. Surgeon General released a bone-chilling advisory titled “Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation,” which recognized the impacts of social isolation and loneliness as an urgent public health issue and revealed that about half of U.S. adults report experiencing measurable levels of loneliness.

The advisory clearly outlines that just as social and physical environments can influence feelings of isolation or reinforce connections, digital environments carry a similar weight — having the potential to enhance or detract from our quality of life. And consensus is, today’s digital platforms have contributed to historic levels of loneliness.

The impact of social media on our culture and communal well-being is well documented. In fact, the report reads, when technology “reduces the quality of our interactions,” it can lead to “greater loneliness” and “reduced social connection” — having the opposite intended effect of social media’s purpose. The phenomenon can be explained only by jargon derived from social media itself — FOMO, or fear of missing out. Rather than opening an app and feeling immediately connected to our friends and followers, the instant ability to check in on the lives of others introduced greater anxiety and fear of social exclusion into our daily lives.

But FOMO isn’t a glib saying; it’s rooted in science: New findings suggest that people who use social media for more than two hours a day are twice as likely to report feeling socially isolated compared to those who use it for less than 30 minutes per day. We’re reminded again that connectivity can’t guarantee or substitute real, human connection. In fact, it may just do the opposite by making the need feel all the more glaring.

A future with greater connection requires a hard reset

Amid rising isolation, it’s no wonder that consumers time and time again are flocking to platforms that can yield an authentic, engaging digital community — one that offers the chance to participate in real moments and real dialogue.

But social media can’t solve the same issue it feeds — loneliness — without true, exceptional change and a hard reset to place in-person connection at the center.

There have been countless examples of good acts and work forged by social media — of platforms connecting neighbors to one another and resources in times of national need, empowering members of pro-democracy and liberation movements, mobilizing greater civic engagement, and more.

But what all of these examples have in common is the ability to convert digital engagement to community-building IRL (“in real life” for the less online). Or rather, using greater connectivity as a vehicle for building connection and community — not replacing it. We don’t need a wave of social media design that seeks to minimize the impact of these platforms. We now know how powerful they are going to be. Instead, we need a wave of design that imagines a different set of impacts, that move us from myopia to broader perspectives, from isolating and distancing to connection and empathy, from a tribal perspective to the kind of inclusive national and global identities we know we are capable of embracing.

When we revise the hypothesis to read “connectivity in pursuit of connection,” that’s the type of social media that can help aid our loneliness epidemic and quench users’ thirst for a fulfilling platform for once and for all.