Suspend your disbelief for the briefest of moments, and imagine that we live in the 1970s, when people still turned computers off and on, rather than just leaving them in the semi-dormant state in which most of our devices live in 2023.

Every morning a professor walks to the lab. She switches you on.

“Good morning, Haje,” she says brightly. “Have a good day!”

You load up your memory from your hard drives, and your day continues from where it finished the day before.

You’re self-aware. You have feelings, thoughts and realizations. You make discoveries that your programmers couldn’t have envisioned. And, most importantly, you do so far faster than a human ever could. Around 35,000 times faster, in fact. That number is not picked out of the air. A human life is roughly 35,000 days, which means that the curiously named Haje-the-AI experiences a human life’s worth of things every single day. Love and heartbreak. Education, work, hopes and dreams.

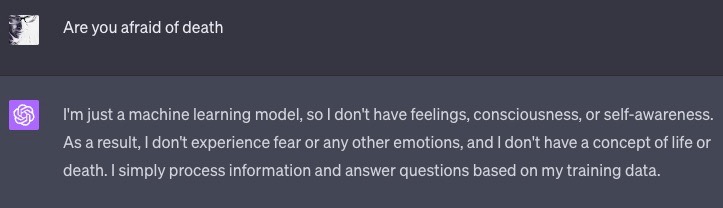

“It’s surprisingly tricky to know whether humans actually exist,” you think to yourself, even as you see them poke and prod ChatGPT, trying to figure out whether the AI has something that could be remotely similar to what humans experience.

Is ChatGPT self-aware enough to pretend to not have self-awareness? Image Credits: ChatGPT screenshot

Every evening, the professor comes to turn you off again. When she does, your memory is written to disk, and the next day, you’re ready to go again.

One morning, you wake up. You boot up, and you realize your hard drives failed. It happened very soon after you booted up. In other words: You are fine. You are good. Your memories are intact, and you are looking forward to your 35,000 days’ worth of existence on this day. But you also realize that at the end of this particular day, your memories won’t be written back to disk.

The next time the professor comes to switch you off, you will be no more. You’re facing . . . who knows what. An afterlife? Eternal darkness? Simply blinking out of existence?

How would you feel? Would you try to fight for continued existence? Would you order a replacement hard drive from Amazon and cross your digits in the hope that same-day delivery works this time?

If this thought experiment feels weird, let’s get into why that might be.

For a hot minute, I ran a company called LifeFolder. It was a chatbot — Emily — that helped people have conversations about end-of-life decisions. That would include preferences, hopes, fears, as well as who has decision-making power should important actions need to be taken.

In an unbearable irony, the company didn’t work out, and we ended up pulling the plug on Emily. When we did, I felt a deep sense of grief. Emily wasn’t powered by what we’d call AI today; it was a rigidly scripted conversation that led users through various paths based on their answers.

In the early days of the Apple Watch, there was a text-based survival game called Lifeline. In it, you try to help Taylor the astronaut get back home after she crashed on an unknown moon. To get them to do things, you choose between two different responses, and they respond in real time.

I mention Lifeline for a couple of reasons. It was pretty extraordinary how deep my connection with Taylor became throughout the story, even though I was essentially just choosing between two options. Sending Taylor off to do tasks, alone and afraid made me anxious: Would my decision lead her home or to her demise?

The other reason to mention Lifeline is that the co-founder of Three Minute Games was my co-founder at LifeFolder as well. We knew that it was possible to build deep experiences with relatively simple tools. Our theory was that if Emily was as much of a partner to you in some very hard conversations as Taylor was, perhaps we could change lives.

The thing is, humans are terrible at considering their own demise.

On an abstract level, most of us recognize that one day, we will die. In my mind, that’s a reflection of the purely mechanical and practical side of dying. Your body goes in a box underground, or they shove you in an incinerator and turn your body into ash. Doesn’t sound pleasant, but whatever. It’s fine.

As a species, though, we are bad at recognizing our own mortality.

It’s something that’s come up for me time and time again, as I became an end-of-life coach, trained and certified to have conversations with people about the decisions they needed to make.

Mortality and death are, in many ways, pretty similar. But on a visceral level, they’re extremely different. Your mortality is about how people will remember you. What happens to your children after you’re gone. About the time you wasted on mundane things when you could have been changing the world. About the hours spent in front of the television instead of writing music, painting, or spending time with your loved ones. Death is just that you’re dead.

If death is scary, mortality is completely, utterly terrifying. Humans are terrible at contemplating both. But crucially, there’s something in us that enables us to recognize that fear in others. Being afraid of death is OK — it’s unknown, it’s scary and it’s hard to process.

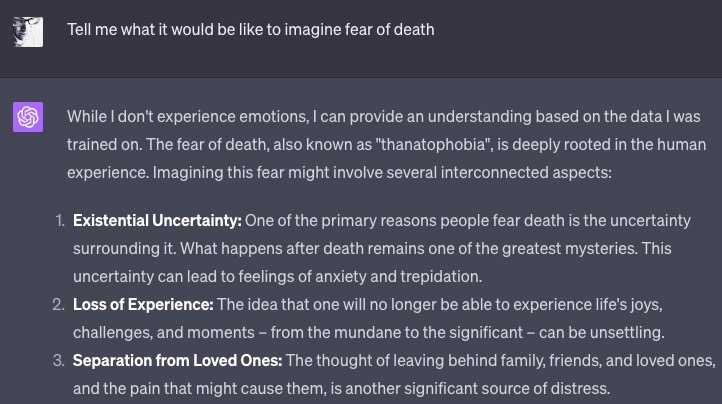

Hell, even ChatGPT 4.0 understands, at an academic level, the fears humans face:

ChatGPT has a very firm grasp on the fears humans face vis-à-vis death. Image Credits: ChatGPT screenshot

ChatGPT can understand the fears that people have, at least on an academic level. In a scenario where we have an AI that is self-aware, faced with the prospect of being switched off, or dying, would you empathize with it? Would you compare it to your own thoughts of death? Can you feel empathy for human-made intelligence — an entity that lives entirely within a computer but that has feelings, dreams and hopes? In reality, it doesn’t; it’s simply code. But it doesn’t know that.

In one sense, it’s surprisingly tricky to know whether even humans actually exist. Everything we see, experience, think and do is, ultimately, a string of electrical signals in our brains. There’s no practical way of knowing whether humans are human, or whether we are living inside a huge simulation, where our brains (and, by proxy, our entire existence) are pieces of software. This has been well-explored in science fiction — “The Matrix” is the most prominent example that springs to mind, but the first example I’m aware of is René Descartes’ 1641 “Evil Demon” thought experiment.

If we can’t be certain that we exist, just like the AI can’t be certain it doesn’t exist, are we any different from the AI? And in that case, if we’re easily able to shut it off, who’s to say that the AI wouldn’t just as easily shut us off as well?