The scrap between Joe Rogan, Spotify, and their detractors has resurfaced the simmering debate concerning creator monetization.

Given that creators include everyone TikTok performers mega-podcasters, YouTube celebrities, and Instagram influencers, no single revenue model will work for them all. But do creators have to employ all revenue models to make their business math-out?

Being cross-platform can be a boon to creators looking for a larger audience, but doing so quickly becomes too much work than one person can handle.

Creators making enough money from their work to get by, let alone prosper, is something of an Internet holy grail. Substack has one take on the question. YouTube’s revenue-split with select creators is another. TikTok’s creator fund was headline-grabbing, but ultimately far too small compared to the number of extended hands. Is any platform doing a good job?

So how should creators think about monetizing their work today? TechCrunch’s Amanda, Natasha, and Alex – after a lengthy chat on the matter – worked to map out some possible routes forward. Here’s how it panned out:

- Amanda Silberling: I’m tired of everything being an ad

- Alex Wilhelm: Not your platform, not your money

- Natasha Mascarenhas: De-risk where possible

Amanda: I’m tired of everything being an ad

My friend Hannah went viral on TikTok for crocheting chicken nuggets (now that’s a sentence that would’ve been incomprehensible three years ago!). She works full-time in publishing, but with her newfound audience of 26,000, she started up an Etsy shop where, you guessed it, she sells crocheted chicken nuggets — which sometimes have hats. She’s made some unexpected cash thanks to her sudden popularity.

Sometimes, when we talk about the creator economy, we’re really only talking about a small subset of creators – people like the kids from Hype House who make millions of dollars through brand deals. Then you have creators like Hannah. She makes money on the internet by leveraging her audience and selling products to compensate herself for the labor of being really funny and really good at crocheting chicken nuggets. It’s a side-hustle, not a full-time job, but that doesn’t make her venture less legitimate or interesting in the greater context of the creator economy.

I’ve already written about how TikTok’s current creator monetization model doesn’t adequately serve creators, and how YouTube’s Partner Program, which operates by sharing a percentage of ad revenue, offers a more generous payout. But I can’t stop thinking about the advertising of it all. You have your YouTube ad revenue, then you have your brand deals, which are essentially just ads disguised as Instagram posts – bigger stars bring in the bulk of their money through brand deals. Even independent podcasters pay the bills through advertising (as well as fan membership programs, merch… diversify your income streams!).

But Hannah is simply out here selling crocheted chicken nuggets (is yarn vegan?). On one hand, she could partner with some yarn companies, make some branded TikToks, then post tutorials on YouTube, earning ad revenue from her videos, which she would make just long enough to appease the ever-ambiguous algorithm.

But brand deals aren’t the only way to build a business. If Hannah’s nugget empire ever expanded to the point where she’d want to abandon her non-yarn-related day job, she might start a Patreon, build a product to help newbie crocheters, or teach crocheting workshops online. Sure, that’s easier said than done, but the point is, maybe not everything needs to be an ad. And if brands’ general excitement about influencer marketing wanes, creators will need other strategies to make ends meet.

I don’t blame people for taking brand deals. Get paid! (I’m not even that mad about Wordle selling to the New York Times!) I’m grateful that brands see the value in these partnerships, because they help some really talented creators get paid to make stuff on the internet that I enjoy. But I don’t want every corner of the internet to feel like Words with Friends, where you have to sift through 12 different ads to just play a game with your grandma.

There are too many creator economy startups already, but if you must join the fray, I’d love to see more ways for creators to connect with (and maybe monetize) their audience.

Alex: Not your platform, not your money

I was a reporter during Twitter’s early years of letting developers run wild with its service. In fact, the first Twitter client I fell in love with was Twhirl, a name you haven’t heard in around 10,000 years as the social network eventually clamped down on access to its content, and we all slowly migrated to first-party services.

The lesson? Not your platform, not your product. For creators, this could be summed up as not your platform, not your money. I think that the tension between platform and creator, both of whom want to maximize their ability to profit, is inherently so tilted in favor of the company that the individual mostly won’t win. Sure, Mr. Beast is making a mint on YouTube, but that’s a bit like saying Justin Bieber got his break posting covers on the service and therefore it’s a viable pathway to super-stardom.

Building a platform is obviously not the solution for most creators, as they are creatives and not engineers. Sadly, it’s also true that most creators aren’t going to want to spin up their own Ghost instances, allowing them to build their own Internet island to rule. This means that they will have to likely grant some power to a platform over their work, in exchange for, well, a platform.

But some creator-hosting services out there are more focused on individual control over central authority. These have always existed, but I would say that the recent Internet era has been more about centralization than distribution — no, we’re not talking about crypto here; sorry, web3 nerds – making them rarer than before.

If creators have to give up some power for hosting, which services are the most creator friendly? We can somewhat consider the question through take-rates. The higher the take-rate, the higher the level of centralization; another way of saying that the higher a take-rate that a platform commands, the more is it what is being sold, versus what the individual creates. YouTube pays out about half, which means that it is more the product than the discrete content being contributed. Substack takes 10%, as it is far less centralized than YouTube (read: less powerful in determining who wins or loses).

Platforms that leave the vast majority of creator incomes in the hands of the folks doing the typing, talking, and videoing, I think, are the places where creators will be able to have the most control, safety, and, therefore, chance to generate material incomes from their core audience.

This isn’t to say that creators shouldn’t TikTok or YouTube or post on Insta. They probably should, but as an ancillary, secondary, or supportive activity over their main remit. Not your platform, not your long-term viability.

Natasha: De-risk where possible

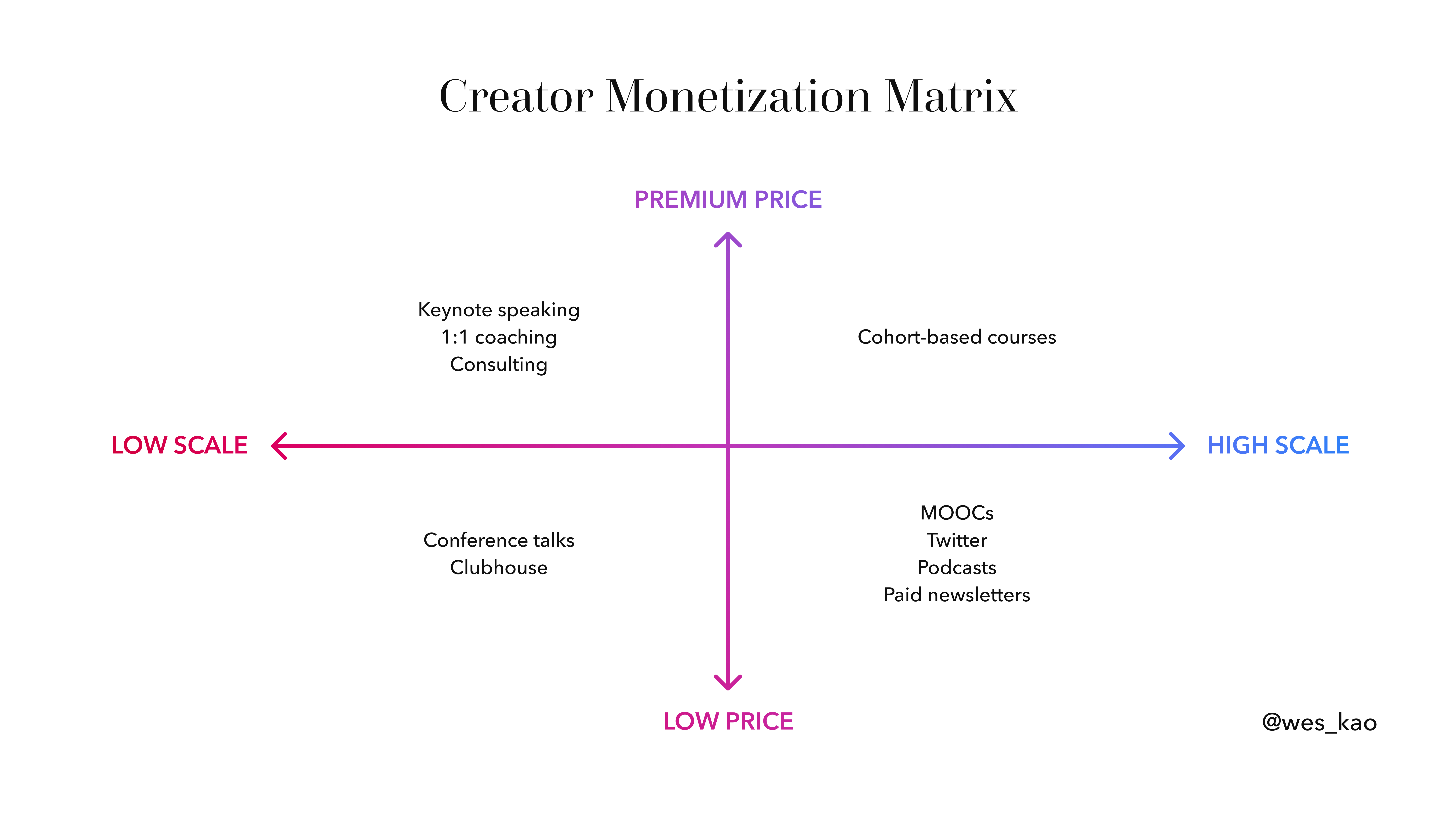

Maven co-founder Wes Kao created a graphic to explain creator monetization through volume and earnings. As you can see, low-scale work that requires creators to consistently “feed the beast” with time can range in earnings, such as a pro bono conference chat or a one-off coaching session. High-scale work, such as cohort-based courses or paid newsletters, can bring a more lucrative check.

Image Credits: Wes Kao

Creators should think about how to make sure their work works for them. While popping up on Clubhouse chats may help the brand, sometimes the best way to scale your time is to publish to a platform that sends the same content to all your different audiences (instead of needing to make content for each independent follower).

Creators are not a monolith. For some, consistent posting is necessary to build an audience that would one day subscribe to a cohort-based class led by you. For more famous creators, a built-in audience could be ready to listen to a podcast on day one.

Kao’s perspective made me think immediately about the allure of going exclusive with a platform. Alex Cooper, the host of popular podcast Call Her Daddy, made upwards of $60 million by signing a deal with Spotify to exclusively host her show on the platform. If you’re that big, and don’t want to deal with distributing your work on other platforms, maybe taking that deal is actually the best way to de-risk. As we’ve seen this week, leaning on Spotify comes with some costs, but it also stops Cooper from the stresses of scaling her work across multi-platforms.

Sure, Cooper still posts on TikTok and Instagram, but it appears to be just to bring more subscribers to her show, or just show a different side of her life. It’s not something we see her monetize in the same way other creators have to, and that’s partly because she’s a big deal.