Former venture-backed startup Casper is going private in an all-cash transaction, it announced this morning. Since its early-2020 IPO, Casper has struggled as a public concern, seeing the majority of its value evaporate after its operating results failed to excite investors.

Casper will sell for $6.90 per share, or around a 94% “premium to the closing share price on November 12, 2021,” per its own mathematics. When it listed, Casper sold its stock for $10 per share, rising above $15 per share in its early life before falling as low as $3.18 per share more recently

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on TechCrunch+ or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

Why do we care about one public company’s planned exit from the public markets? Because Casper’s demise as an independent, growth-oriented DTC company details what can go wrong for such firms. And given that we’re seeing cash-hungry operations like Sweetgreen and Rent the Runway list, it’s worth digging into what happened at Casper.

This is not to say that every direct-to-consumer (DTC) company is the same. Or even that Casper is entirely DTC; it isn’t. But we can learn from Casper all the same because it provides a living example of how a company can struggle post-IPO.

This is not to say that every direct-to-consumer (DTC) company is the same. Or even that Casper is entirely DTC; it isn’t. But we can learn from Casper all the same because it provides a living example of how a company can struggle post-IPO.

When we examine its results, it’s clear that cash was the issue and that the company’s share price likely prevented it from saving itself, while also providing an avenue for external rescue.

What the Casper saga means for DTC companies more broadly is nuanced, but we’ll take that on at the end. To the numbers!

Why Casper had to sell

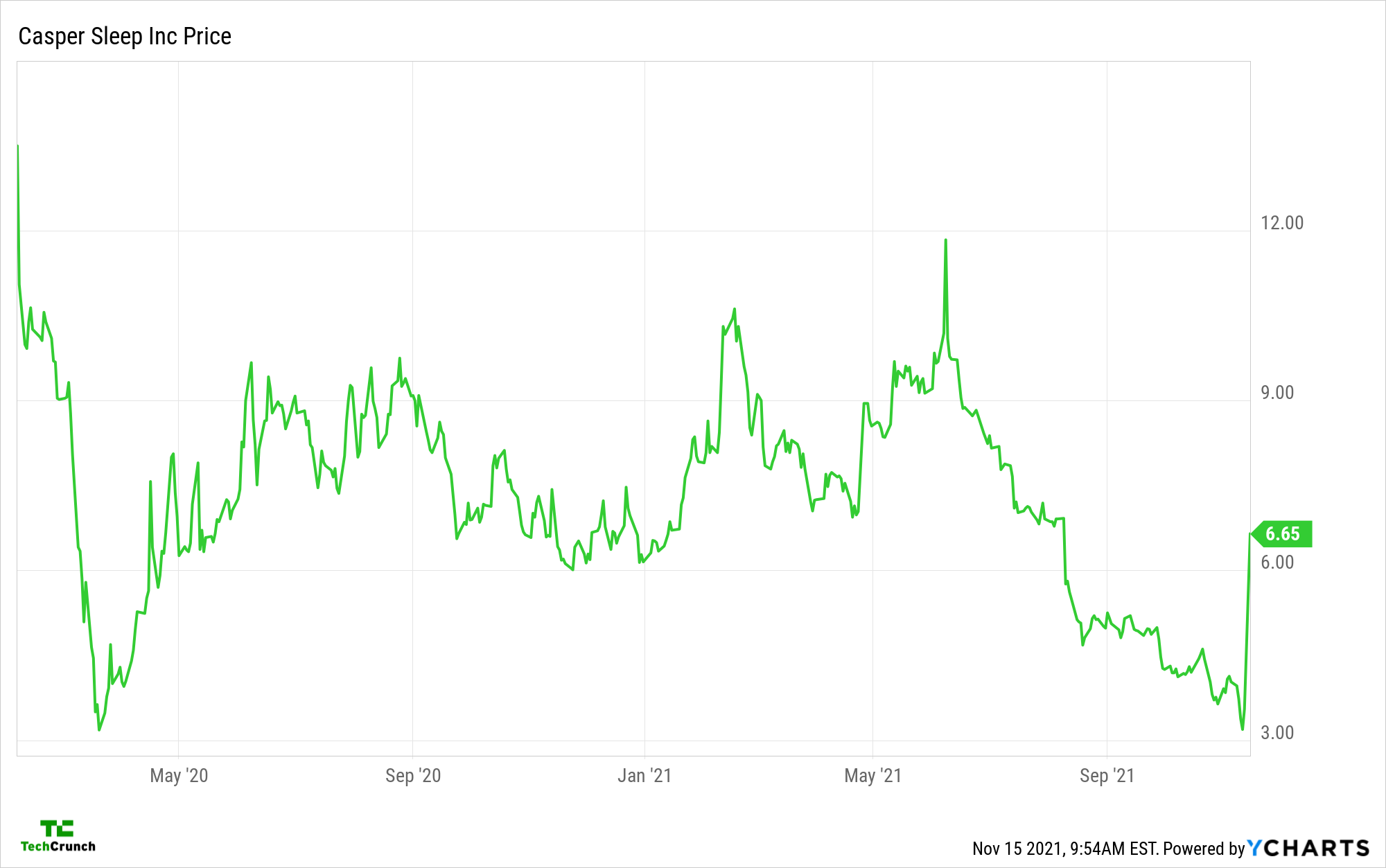

Casper’s exit might feel like an inevitability in retrospect, but it’s worth remembering that the company enjoyed a brief return to pricing form earlier this year:

Image Credits: YCharts

Since that summer high, however, Casper endured its second negative run to a price level that made it an obvious takeover target.

Why did Casper lose so much momentum? In its second-quarter earnings, the company managed a very modest revenue beat ($151.8 million), but a larger than expected loss ($33.7 million). And Casper forecast modest growth in revenues for the third quarter, when measured on a quarter-on-quarter basis.

The same set of results was largely repeated in Q3, with the company besting revenue expectations by a slim margin ($156.5 million), but losing more money than expected ($25.3 million).

Those two sets of earnings help explain why Casper is selling itself: It is simply too unprofitable and too cash-consumptive to keep rolling solo. Here’s a set of data points that will make the situation clearer:

- Casper cash and equivalents, December 31, 2020: $88.9 million.

- Casper cash and equivalents, September 30, 2021: $43.1 million.

- Casper cash consumed by operating activities, three quarters ending September 30, 2021: $38.4 million.

You can chart a line to zero pretty easily from those figures. And a business doesn’t run out of cash the moment it loses the last dollar in its bank account. Run a company too close to zero cash and its suppliers can get spooked about future payments, demanding more cash upfront, exacerbating the cash crunch.

Casper, therefore, had two options, we think: Sell or raise more capital.

The latter would be the 2021 thing to do, but at issue was the company’s share price. If it wanted to raise funds, it would have likely needed to sell stock to do so. Selling more shares would have boosted shareholder dilution and likely further harmed its share price. And given that the company was trading for such a low per-share figure, it would have had to sell lots of stock to generate enough funds to self-power its future.

Hence the sale. Now Casper can get rid of its public life and perhaps figure out its operations while under the custody of a new parent company.

Simply put, Casper failed to grow quickly enough to excite investors enough to have a strong share price. Thus, when it needed more money to keep operating, it was already on the back foot in terms of its value, leading to Casper not having as many options as you might expect. That’s our read.

What does the Casper exit mean for DTC companies more broadly?

It’s not fair to compare every company’s business to the economics of software. Software sports high margins and often a high level of recurring incomes. It’s good shit, in other words.

Casper, in contrast, has lower margins and a far-slower recurring revenue component given that most folks do not buy that many mattresses. Throw in slower-than-expected growth, and it isn’t impossible to see why public investors struggled to value it more richly.

The company also seems to have failed the operating-leverage test, i.e., top-line growth failed to convert to improved profitability. Observe:

Image Credits: YCharts

That chart lacks the most recent data, Casper’s Q3 results, but you can get a feel for the company’s lack of ability to drive improved profitability on the back of revenue growth from the historical results.

The Casper lesson gives DTC companies that want to go public a set of requirements: Either grow quickly enough that losses feel secondary, leading to share-price appreciation and the ability to self-fund growth as needed or find a way to trim losses in the face of slowing growth, making a value pitch to public investors instead of a growth pitch.

Having somewhat failed at both, Casper is selling. You can apply our rubric to Warby, Rent the Runway and Sweetgreen at your own leisure, but it’s at least worth considering that people buy glasses, garments and salads more frequently than mattresses.