As the neobanking boom has matured into a collection of large digital banks, we’re slowly getting a better picture of the economics of such business efforts. Chime was early in telling the market that it was EBTIDA positive, for example, unlike less profitable European neobanks.

The upcoming Nubank IPO — technically the public offering of Nu, but we’ll just say Nubank for simplicity — provides us with far more information and detail regarding the operations of a neobank at scale, thanks to its newly public filing.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on TechCrunch+ or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

In good news for its peers that may seek to go public, the numbers Nubank has shared seem to make pretty reasonable business sense.

We will have more notes in time regarding the company’s offering, its shareholders, its varying business lines and more. This morning, we’re narrowing our focus to the broad economics of neobanking and will end with an examination of Nubank’s aggregate financial health. We’ll take just a second at the end to test a few valuation marks against what we find.

Building a neobank at scale is not cheap. Leading startups and unicorns in the market niche have raised tectonic sums of capital to get to where they are today. But what did all that cash buy them? In Nubank’s case, quite a lot, it appears.

The economics of neobanking

Nubank is one of the most valuable startups in the world, with over 40 million users across Brazil, as well as Mexico and Colombia.

Neobanks, like any consumer product, can be viewed through the lenses of customer acquisition costs, customer monetization and activity, and long-term revenues. We want to know what Nubank pays to attract new users, how their product use and rates thereof translate to income and how much the fintech giant can juice users for over a longer time horizon.

Customer acquisition costs

Nubank is proud of its customer acquisition costs (CAC). The company states in its F-1 filing that its CAC was “US$5.0 per customer of which paid marketing accounted for approximately 20%” for the first three quarters of 2021. That’s lower than we anticipated, frankly.

As we learned in Nubank’s TC-1, the company’s wide geographic presence, alongside its proliferation of offerings, have triggered a wide number of competitors that claim to give a more niche user experience. Numbers today show that growing activity in the broader neobank space hasn’t hurt Nubank’s ability to attract customers.

The financial giant added that it has “acquired approximately 80%-90% of our customers organically on average per year since our inception.” That speaks to strong word-of-mouth marketing, and essentially, lower demand to pour capital into sales and marketing costs.

If the company’s CAC is really as low as it appears, we should be able to see efficiencies in its sales and marketing costs when we get to its income statement.

Nubank’s IPO filing makes it plain that, at least in certain markets, it is possible to grow a neobank to scale with modest CAC.

Customer activity and monetization

Nubank had 48.1 million customers as of the end of Q3 2021. That figure grew at a 110% compound annual growth rate since the end of Q3 2018, per the company. Those customers are pretty active to boot, with some 73% counting as “monthly active customers” as of September 30, 2021.

And they’re still coming. According to the filing, Nubank “added an average of over 2 million net new customers per month across Brazil, Mexico and Colombia combined” in Q3 2021. The company has also seen a rising percentage of daily active customers as a fraction of its monthly active customers, with the ratio rising to 47.9% at the end of this September from just over 41% at the end of 2020.

Investors concerned that Nubank’s growth could slow may relax on the possibility of these new customers stacking up material revenues over time. Nubank said customers tend to generate more revenues over time, with its 2019 cohort — to pick one from the offered data points — generating 5.5x the revenues in the year ended September 31, 2021 than they did in their first year.

That implies goodly stickiness and per-customer revenues. The latter is measured by Nubank in terms of “monthly average revenue per active customer,” or Monthly ARPAC. Here’s where Nubank finds itself today:

For the three months ended September 30, 2021, our Monthly ARPAC was approximately US$4.9. For customers who were active across our core products, which include our credit card, NuAccount and personal loans, we had monthly ARPACs in the US$23 to over US$34 range for the month of September 2021.

The result of sticky customers, and what feels like strong monthly ARPAC when we consider the company’s CAC expenses, together lead to cost-adjusted CAC payback periods of less than a year, at least in the Brazilian market (Nubank’s home turf).

Nubank’s IPO filing indicates that neobanking customers can have attractive usage patterns, growing revenue results and good long-term economics, even if CAC payback periods are still measured in quarters instead of months.

What about long-term value?

The filing provides us with some very basic LTV data. The company’s LTV/CAC ratio — how much more each customer is worth in revenue terms when compared to the cost to acquire them — is “greater than 30x,” per the company’s estimates.

Recall that in enterprise SaaS, you want this number to be greater than 3x. Sure, we’re talking consumer here and not B2B, but 30x is still very attractive.

Nubank’s LTV/CAC ratio implies that efficient neobanks can spend on customer acquisition at even higher levels than it is now without upsetting their overall economic profile.

What does all that add up to?

All the ancillary metrics in the world don’t sum to a hill of beans until we sink our teeth into a company’s GAAP results or overall income details set to a standard of measures that we fully understand. But since Nubank is a Brazillian company, we’re not dealing with GAAP — we’re delving into the world of International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS). Which is equivalent, mostly.

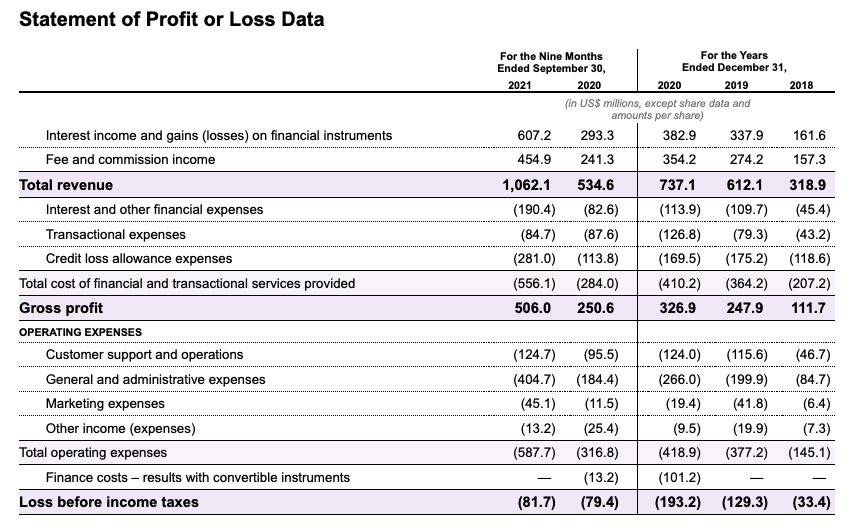

Here’s the income statement, including all data before taxes are taken into account:

Image Credits: Nubank

Note that the data is presented in millions of USD, so the company’s revenues through Q3 2021 were $1.06 billion.

A quick scan of the income statement shows a rapidly growing business with losses also creeping higher with time. However, for a company of its scale, Nubank’s losses do not appear even close to lethal. Indeed, they are more modest than we anticipated.

The pace of growth in red-ink terms is slowing. Despite effectively doubling in size during the first nine months of 2021 compared to the same period of 2020, Nubank’s losses only ticked up a small amount. We think the company should be able to begin lowering its losses and start charting a path to profitability in the near future.

Growth is simpler to understand. From 2018 to 2019, Nubank nearly doubled its revenues to $612.1 million. After that stellar period, 2020 was a let down, with the company managing far slower growth to just $737.1 million in total revenues. Notably, marketing costs fell in the year, perhaps due to COVID-19 and its related disruptions to the global economy.

Growth has re-accelerated to the roughly 100% range this year when compared to 2020. Expanding top line from $534.6 million in the first to third quarters of 2020 to $1.06 billion in the same period in 2021 is very good, and nigh incredible when compared to the company’s aggregate growth pace in 2020. If Nubank had spent just a few million less on marketing during the nine-month period, it would have managed a flat net loss over the same time frame.

We noted earlier that if Nubank was seeing the sort of low-CAC, high word of mouth marketing lift that it claimed, we should see modest sales and marketing costs in its income statement. We do. The company spent just over $45 million in the first nine months of 2021 on sales and marketing costs. For a company doing over $1 billion in revenue during the same period and growing at around 100%, that’s essentially zero.

Nubank’s IPO filing details that if a neobank can sport attractive user acquisition metrics, the lack of spend can open a quick ramp to profitability. Neobanks that lack a similar growth engine may demonstrate steeper losses and a less salubrious overall economic profile.

What’s it worth?

Nubank was last valued at roughly $30 billion a few months ago when it raised $750 million. What is worth now? Using its revenue result from the first nine months of the year, the company is on pace to report revenue of around $1.42 billion, though that number is conservative, as we used a three-quarter time frame to generate a run rate instead of its most recent quarter times four, as we lack the data for that calculation.

Regardless, the company has around a 21x revenue multiple at its final private-market price, and its undercounted revenue run rate. For a company with roughly 50% gross margins, that may seem slightly high. But with long-term customer revenues effectively generating SaaS-like revenues, investors may be willing to pay more attention to Nubank’s growth than its margins.

That may explain why the company is expecting a valuation of around $50 billion when it trades.

That price would be killer news for other non-banks looking to list, as it would imply that full-fat private-market valuations can find support from public investors. Speaking of which:

What’s next?

Nubank isn’t the only neobank heading to the public markets. PicPay, which filed for a $100 million IPO on the Nasdaq in April, is a fintech platform that combines a Venmo-style P2P element with e-commerce and social networking. We also have Chime, which raised a $750 million Series G in August and is reportedly going public by March 2022 at a valuation between $35 billion to $45 billion. Monzo, a U.K. challenger bank which has raised nearly $650 million, has said in interviews that an IPO is on the horizon, as did Starling Bank.

In the coming months, investors will have first looks into the financials of a fee-free, consumer-focused banking startup, which could usher in another slew of exits or at least validate some of the private market funding frenzy. Fresh metrics could prove that neobanks are finally moving off their investing phase — spending a lot of money to eventually make a lot of money — and into a more stable, recurring revenue world.

Based on Nubank’s F-1, the transparency and liquidity will be good news for neobanks.