It seems there’s news every day about startup funding reaching record highs, new unicorns being minted and tech firms going public. There’s no question that we are in the middle of a long-running and accelerating venture bull market.

All of this impresses upon us that every indicator in startup funding points up and to the right: Venture firms have more dry powder, deal sizes are growing rapidly, valuations are soaring and investment terms are more founder-friendly than ever. And all that is indeed happening.

But a closer inspection reveals that these trends are a lot more nuanced and apply very unequally across the funding continuum from seed to the late stage. What’s more, most of the underlying truths and rules are not changing.

The venture alphabet soup of “A, B, C rounds” suggests it’s all the same, just one after the other, but it is not. It is more like playing an entirely different sport.

Beware of the outliers

The stage definitions in venture, from seed to late-stage Series D, E or F rounds, have always been open to interpretation, and general patterns are challenged by outliers at each stage. Outliers — unusually large financings with high valuations relative to the company’s maturity — are as old as the industry itself. But these days, there are more of them, and the outliers are more extreme than ever before.

For example, Databricks raised two massive private rounds, a $1 billion Series G and a $1.6 billion Series H, in 2021. These funding rounds are bigger than many IPOs in the recent past, and Databricks is far from the only company to do something like this. There were an average of 35 “megadeals” (with over $100 million raised) per month from 2016 to 2019, according to Crunchbase. In 2021, that number stands at 126 per month.

This is mainly due to two major trends. First, the extremely lucrative exit market has created the economics to support mega late-stage rounds and venture rounds of $100 million or more. And, companies are staying private longer, and they need additional late-stage capital before an IPO that companies historically did not need. More on that below.

What is important for now is to acknowledge the simple truth that aggregates and averages don’t tell the real story of the broader market. The median of funding round sizes and valuations give a better view of how the market is really doing. So when you see the next report on a record venture funding month, pay close attention to what is being heralded.

Stages behave very differently

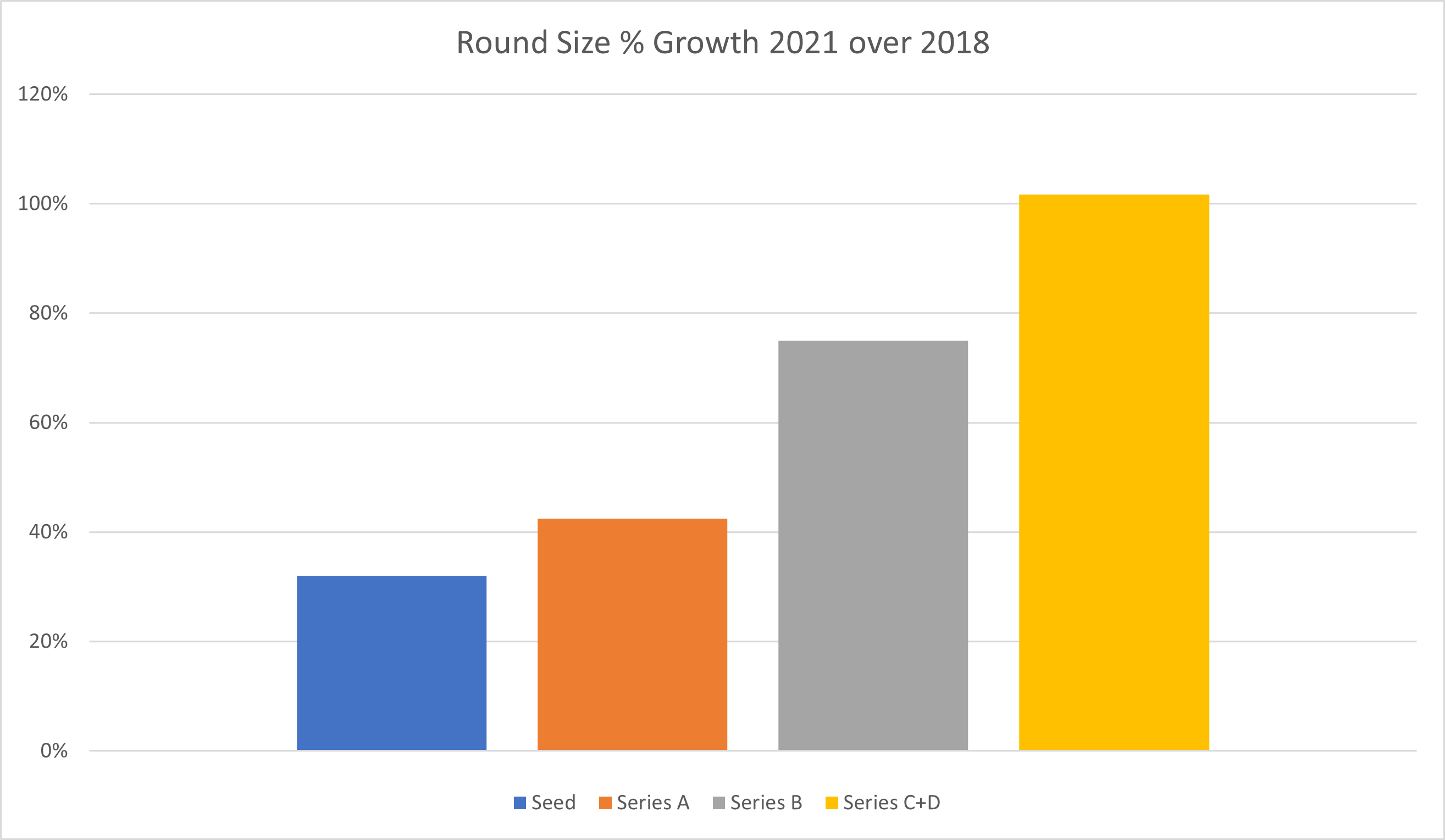

Most people think the substantial growth applies across the funding continuum, but that is not really the case. In fact, the venture bull market affects different stages very differently. The following is based on Cloud Apps Capital Partners’ analysis of PitchBook data on fully documented U.S. financings (seed through Series D) in the cloud business application space since 2018 through the first half of 2021.

The biggest impact appears to be in the late stage. For Series C and D financings as a group, median round sizes more than doubled to $63 million in 2021 from $31 million in 2018. Pre-money valuations grew by 151%, and ownership — the share equity investors in the round collectively own after the financing — dropped to 12% from 18%. So the money involved has doubled, but Series C and D investors ended up owning a third less than they used to.

Now let’s contrast that with early-stage funding rounds. Median round sizes for Series A fundraises grew by a modest 42% to $13 million from $9.1 million, and seed rounds only grew 32% to $3.3 million from $2.5 million over the same period. Growth in valuations was very similar and the ownership stakes of seed and Series A investors remained essentially the same from 2018 to 2021, hovering around 27%-29%. Very interesting, don’t you think?

Series B results were between the two extremes, but it is important to note that this analysis did not even look at the “late, late stage” brought about by companies staying private longer. The “mega rounds” discussed above often happen only after the Series D, and comparisons of the Series E, F, G and H rounds would surely show even greater acceleration.

Image Credits: Cloud Apps Capital Partners

A tale of two cities

There is a lot here to discuss. Late-stage investments are very different by nature — they are primarily financial investments. What we mean is that a financial analyst has a lot of hard data to help determine the quality of a deal. The company is already working, growing and producing a lot of quantitative insights and SaaS metrics. As a result, the risk is lower (fewer companies fail after a late-stage investment) and it is easier to pick out the winners. Also, you need much less time to take companies from the late stage to a public exit.

Combine these facets with the strong IPO market and the lack of many high-yielding investment alternatives, and it is no surprise that investors are keen on late-stage pre-IPO deals. And the investors aren’t only venture firms. Over the past few years, there has been a flood of non-traditional investors, like private equity firms, hedge funds, mutual funds and pension systems, into the late-stage venture market. This is mainly due to the low-risk, lucrative internal rates of returns (IRRs; 10%-15% compares favorably), shorter hold times (three- to four-year medians) and the fact that no special skills or operating experience are required.

It should come as no surprise that the additional capital and competition has driven up financing metrics in Series C and D and beyond. As long as the IPO market supports it and still offers enough of a step up (lately about 1.5x of the last round pre-exit), this acceleration in the late stage should continue.

Early-stage investing

Comparing that with early-stage investing at the seed or Series A stage gives very different results. The venture alphabet soup of “A, B, C rounds” suggests it’s all the same, just one after the other, but it is not. It is more like playing an entirely different sport.

At the early stages, companies are completely unproven, they may or may not have a production-ready product and certainly will not have product-market fit. The go-to-market motion — whether direct, channel or product-led growth to small or midsized businesses or the enterprise — is at best a plan with a few early successes, and there is no financial data or track record, and few SaaS metrics.

The analytical types who like to pore over data to assess deals don’t have much to study.

Early-stage investing is about understanding the market, the competitive landscape, projecting market size and adoption dynamics and assessing the entrepreneurial skills of the founding team and their technology chops and vision. That’s why it is so much harder to see and pick the winners. It requires operating experience and special skills; it’s more art than science.

And something else is crucially different: It takes more time and effort. For cloud businesses, the path from seed to public scale and exit can easily take eight to 10 years. The Series A investor becomes board director and often stays on for many years as a trusted adviser to the founding team. So there is considerable effort involved and the time commitment can be massive.

The ripple effect

These reasons are why the financial calculus for early-stage investors is, and must be, different. It is very high risk, very high return. Series A returns stand out above other rounds — annualized returns (IRRs) are in the high 20s versus the low to midteens for all others.

But why can’t higher public exit valuations allow early-stage investors to relax their pricing discipline? Shouldn’t those higher returns justify that? Well, maybe a little, and that’s what the data shows — a 30% to 40% increase in round size and valuation in 2021 compared to 2018.

That expansion is driven by increased competition. As non-traditional investors pour into the late stage, VCs come in a little earlier to where the non-traditionals are less comfortable. The VCs who were focusing there slide a bit earlier, in turn. This ripples all the way through, with most firms “going earlier” than they did historically, which also reinforces the growth in funding round sizes, as each firm has funds to invest and is used to writing checks of a certain size.

This is true all the way back to early-stage rounds, but, as we saw, the effects are muted. Remember, those IPOs are eight or 10 years away, and no one knows what the market will bear then. More importantly, most of the early-stage math is about success probability: After all, a large share of these investments will not see or benefit from IPO-scale exits, but will fail or get acquired along the way. Seasoned early-stagers are therefore fighting tooth and nail to maintain pricing discipline.

Because the fundamental game at this stage is still the same.

The lure of the big check

So what should you do as a founder if at the seed or Series A stage you have — as the result of VCs “going earlier” — the choice to raise more capital at a better valuation? The answer obviously depends on your company, the market, the TAM, the competition, how proven the product is and a myriad other factors.

But it also depends on the founders’ experience and mindset. There are those who believe in their ability to deliver immense growth and reach public scale in five years. These folks go for the big check early and go back to the well often. Some of them do succeed. Those companies are the big success stories we hear about the most.

But there are many more who struggle to deliver. They have good businesses that grow, just not fast and efficiently enough. The seed and Series A checks are written on promise, potential and opportunity. The Series B, C and later-stage checks are written on hard facts, growth numbers and SaaS metrics. If your market wasn’t as big, the urgency to buy not as high, your initial product didn’t quite fit or your leadership team didn’t click and you miss those metrics, what follows are painful down rounds that dilute founder equity very quickly.

I often think of an airplane barreling down the runway: If you pull the yoke back too early or try to climb faster than the airspeed allows, you stall — and bad things happen.

Let’s not forget that even if you did everything right and managed to achieve accelerating growth with strong metrics, what happens if those late-stage valuations come back down to earth? If — or should we say, when — there is a long-term valuation adjustment in public and late-stage private markets, founders who raised large early-stage rounds at high valuations will find themselves in a world of hurt and most likely lose considerable equity in the process.

Experienced founders get it

We find that most experienced founders understand this. They know it’s a marathon and not a sprint. They have the discipline to go for the smaller check and prioritize differently. They focus on a partner with operating experience, time, a network, patience and the understanding that they are in for the long haul.

These founders take the time to mature their business, product, GTM and team to the point where the company can handle the pressure of faster growth and deliver on those SaaS metrics. Only then do they inject more capital and face the higher expectations it comes with.

We get it. It is tempting and hard to forgo that $12 million Series A at a $40 million pre-money instead of just a $5 million round. Until you realize that following that $12 million Series A with anything short of a $120 million pre-money Series B will cost you a lot of equity. That valuation requires at least $5 million to $6 million in annual recurring revenues with sufficient growth and good metrics, which might be much harder to achieve so quickly than your optimistic self is willing to admit.