Amazon commands a vast, dominating empire in the world of e-commerce. While its marketplace has proved a boon for businesses trying to get off the ground, many of the more successful companies are now looking beyond the e-commerce giant’s fences, spurred by a desire to compete on their own terms.

This trend has mushroomed as online shopping burgeoned over the past five years. Businesses such as mattress maker Casper, men’s personal care brands Harry’s and Dollar Shave Club, footwear and apparel makers Allbirds and Zaful, gadget store Banggood, and power-bank maker Anker are just a few of the multitude of brands that choose to leverage their own web stores, social media presence and supply chains to build their business and identity without having a marketplace like Amazon get in the way.

Every investor and e-commerce exporter we spoke with noted the genius of Shein’s supply chain management.

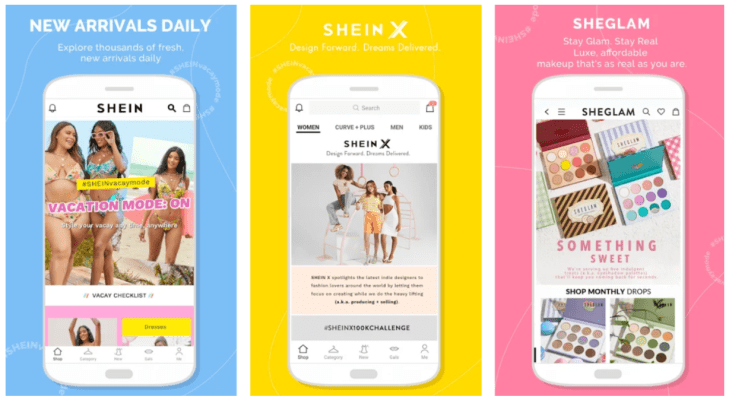

Shein, an online-only apparel store that sells the latest in fashion at very affordable prices, is a shining example of this trend. It’s a rage among budget-conscious young adults across Europe, Asia and the Americas: The app was downloaded 14 million times in the United States in March, according to Apptopia, and currently dominates the shopping category in app stores in over 50 countries.

Its success is proof of its belief in bringing the latest trends to the masses as quickly as it can. In the past couple of decades, brands like Zara, H&M and Forever 21 earned themselves the “fast fashion” moniker when they turned the tables on global behemoths such as Gap and Calvin Klein by drastically shortening lead times — the time it takes for clothing to reach the store floor from the designer’s desk.

Shein takes this fast fashion mindset one step further: While brands like Zara and H&M take about three to four weeks to bring clothing from the ramp to the store, Shein uses a combination of real-time customer and predictive analytics, hyperaware fashion designers and an extremely quick and agile supply chain based in China to bring the latest fashion trends from Instagram, Facebook, Reddit and TikTok to its online store in just a week or two.

Just like its fast-fashion predecessors, Shein has had a lot of success in making fashion faster. Its daily active users grew 130% to 2.6 million in the past year, per Apptopia.

Following in their footsteps, Shein intends to try its hand at revolutionizing fashion. “Shein is building a next-generation brand that is highly personalized, where consumers play a big role in determining what to manufacture, instead of being told by big fashion icons what they should wear,” said Min Wanli, former chief scientist of Alibaba Cloud who founded North Summit Capital in 2019 to fund digital applications in traditional sectors.

“Real-time retail”

Every investor and e-commerce exporter we spoke with noted the genius of Shein’s supply chain management.

Shein’s business model requires rapid production of clothing at low prices, but it can’t do this without a flexible and fast supply chain. In a way, it is like Zara 2.0, said Richard Xu from Grand View Capital, a Chinese venture capital firm backing cross-border businesses. Zara’s supply chain is already more flexible than those of traditional apparel brands, but it further compresses the product cycle from weeks to days.

“Shein’s goal is to beat Zara, H&M and so on,” said Jacky Bai, a Shenzhen-based Amazon merchant.

Once Shein’s designers have a concept in mind — these may be inspired by social media, fashion shows or competitor products — they quickly sketch up a design to be prototyped in-house. The designs will then go into production at Shein’s factories in Guangzhou within a few days, and within two weeks after the design is first conceived, the finished product will have traveled across the globe through Shein’s logistics fulfillment partners, landing in the U.S., Europe or South America.

Thousands of new items, or what the retail industry calls stock-keeping units, hit Shein’s virtual shelves every day. When an item sells well, Shein uses its real-time sales tracking to instantly ramp up production for the product, selling even more, Min said.

To achieve all of this, Shein has fostered close ties with clothing suppliers around Guangzhou, a manufacturing hub in southern China, over the past decade. Unlike their counterparts in eastern China, which supply international luxury brands, Shein’s suppliers tend to specialize in more affordable clothes and can turn around production quickly.

It approaches these manufacturers with large orders and long-term contracts, which “are a boon for small factories, so they are happy to work with Shein,” said a Shenzhen-based venture capitalist who focuses on China-based consumer brands targeting overseas markets.

The responsiveness of Shein’s supply chain also stems from its adoption of enterprise software in all facets of the business, from material procurement and production lines, to inventory management and delivery. Because business procedures are monitored digitally, Shein knows the optimal route for its trucks traveling between factories, warehouses and airports. It knows how to allocate shipments to minimize freight costs and how changing tariffs may affect its profits, based on which it makes adjustments to logistics.

“It took Shein a very long time to iterate and build up a so-called agile supply chain system, which some call a ‘real-time’ supply chain,” said Xu.

No shortcuts to success

None of Shein’s strategies are rocket science, but they are the result of years of meticulous operation and iteration.

“In e-commerce, much of a company’s competitiveness is its lessons learned from trials and errors. There are a lot of venture-backed companies that want to copy Shein now, but it takes a lot of time to accomplish what Shein has. It’s hard to catch up with Shein even if you’re deep-pocketed,” Xu said.

Having its own app is also key to Shein’s sustained growth and popularity. The ability to collect customer information and communicate with its users lets it leverage those insights to offer better products than it would have been able to via a platform on Amazon or other major online marketplaces, as they don’t allow merchants access to customer information or users. “All the sellers on Amazon and China’s dominant e-commerce site are effectively working for these platforms. They have little or no access to user insights,” said Min. “Those insights can determine how you produce.”

Shein’s competitors are going around Guangzhou trying to woo its suppliers, but the company’s ties with factories are proving hard to break. To keep suppliers loyal, Shein is quick to pay their invoices and it even helped sell off their excess stock in the early days of its partnership.

“There are simply not enough manufacturers in Guangzhou to fulfill all these demands,” said a Shenzhen-based investor who has visited some of Shein’s factories. “They are already preoccupied with just fulfilling Shein’s orders.”

While Shein sells its apparel for much less than Zara and H&M (its summer dresses cost between $5 and $20), rather than squeezing the margins of its suppliers, the company keeps the prices low by accepting thin profits.

The rapid growth and low profits have, however, meant that Shein’s journey has been capital intensive. But this playbook is a familiar one in the Chinese tech industry: Offer cheap or even free products to quickly attract a large user base and monetize later on by selling more lucrative products. Shein doesn’t intend to make money in its early years, but as its repurchase rates increase and the cost of user acquisition falls, it has begun to generate a thin profit margin of around 5%, according to the Shenzhen-based investor.

As of its Series E round, its investors included IDG Capital, Greenwood Asset Management, Sequoia China, Tiger Global, Xiaomi founder Lei Jun’s Shunwei Capital, and one of Japan’s oldest venture capital firms, JAFCO. The company declined to disclose how much it has raised, but said its valuation was at the “billion-dollar level” as of its last funding round about a year ago.

The company is already branching out beyond clothes and accessories. Its marketplace now has a section featuring pet supplies, personal care products and home decor. These aren’t necessarily high-margin products, but the move is a red light for marketplaces like Amazon, showing how companies like Shein can easily broaden their offerings on the back of a solid user base and robust supply chain.

Shein’s success has spurred more Chinese investors to enter the massive e-commerce export market. Many of these, according to a manager at Amazon China, are looking to invest around the Shenzhen area, which is adjacent to Guangzhou and home to swathes of Amazon merchants.

But the market in which Shein and its peers thrive is radically different from the high-minded internet world with which most venture capitalists are familiar. Many Chinese sellers on Amazon hail from humble economic backgrounds with only high-school diplomas, said the Amazon manager. They used to roam Shenzhen’s electronics markets hunting for lucrative white-label products to export, and when they discovered Amazon and eBay, they switched swiftly to selling online. And in doing so, they also brought with them the gritty, ravenous and sometimes fishy business practices.

“Entrepreneurs and investors underestimate the difficulty of cross-border businesses. It involves a lot of hands-on, minor details. [Shein’s founder Chris] Xu is from the grassroots, but a lot of the people following in his footsteps have shiny resumes. It’s not that easy to copy him,” said the Shenzhen-based investor.

Grand View Capital’s Xu concurs: “When you are on Amazon, the platform takes care of everything. When you have your independent store, you are in charge of many things, from inventory, logistics, to payments. That’s why very few independent stores have succeeded.”

The China factor

With operations across three continents, Shein is well known now. But beyond what can be inferred from third parties, there is surprisingly little to be learned about the company.

Shein has kept a low profile since its inception. There are no interviews to be found of its executives, and it has never boasted of its funding. There is no indication of it being a Chinese company across its website or app. Even the origin of its product shipments is kept vague and packages are often dispatched from warehouses in customers’ vicinity.

There’s even some confusion about where and when it was founded. A Shein spokesperson told TechCrunch that founder Chris Xu came up with Shein’s business model in 2015 during a stay in Los Angeles.

However, six people with knowledge of the industry told TechCrunch a different story. They said Xu founded the company in Nanjing, a city in eastern China known for its historic heritage, back in 2008. The firm apparently focused on building its own independent store from the outset, but used Amazon and Google to test what would sell well. Its own brand only began to take off about five years ago. Today it has operational teams in Nanjing, while its supply chain operations are based 1,400 kilometers away in Guangzhou.

“It’s hard to pin down where Shein is from. It’s a company with operations and supply chains in China targeting the global market, with nearly no business in China,” Grand View Capital’s Xu said.

The firm says it now has a global headquarters in Singapore with localized teams in major markets to support customers worldwide. Singapore was apparently chosen as a launchpad for its global expansion — a predictable decision given the city-state’s perceived political neutrality — and business registry information shows that Shein deregistered its Nanjing entity this April. This, according to the spokesperson, was a “normal procedure” after the company evaluated the demand for its global operations and reorganized its corporate structure.

To many, however, all this seems as though Shein is hiding its Chinese identity to avoid scrutiny overseas. “Some companies choose to be global from day one, and that’s completely fine … Other companies avoid being called Chinese due to negative public perception,” said Xu.

It may also have to do with competition. “All e-commerce exporters are very secretive about what they do to prevent competitors from cloning them,” said the Amazon China manager.

Nevertheless, the company’s Chinese ties may have become a sticking point as it grows amid rising geopolitical tensions over the past decade — its app was banned alongside dozens of other Chinese apps in India, for instance.

Shein has garnered a wave of media attention since it began to trend on top of the app store charts, but not all of it has been positive. A widely circulated Substack newsletter brought to light the firm’s clever use of influencer marketing. Bloomberg examined how Shein gamed the tax systems and The Financial Times highlighted its trademark infringement troubles. The environmental consequences of the platform’s cheap, disposable garments also got The Atlantic looking into it.

The company no doubt needs to step up its public and government relations — it currently doesn’t even have a PR department — if it plans to continue growing at its current pace.

“I think [not disclosing your Chinese association] has to be addressed in the long term because you can’t avoid having a geographic location forever. It’s not good for future plans. I think Chinese companies have to speak first before foreign media speak for them,” Xu suggested.

The Amazon challenge

In May, Amazon shut down several major Chinese merchant accounts on its marketplace. The exact reasons weren’t disclosed, but the consensus in the industry was the e-commerce behemoth was punishing merchants for black hat tactics like posting fake reviews and obtaining buyer information from under its nose.

By prioritizing its buyers, Amazon often risks compromising third-party merchants, who have to stomach hefty inventory costs, fierce competition driven by reviews and rising marketing fees.

“Often it’s more economical to risk having your store shut down than doing nothing to bump your reviews or ask for users’ information,” said Bai, the Amazon merchant.

A popular saying that captures the reality of both Amazon and China’s e-commerce ecosystem, goes: Faking reviews is like seeking death; not faking reviews is like waiting for death.

For companies struggling to compete on marketplaces like Amazon and Alibaba, Shein shows an alternative path to succeed in the global e-commerce landscape, inspiring a raft of disheartened sellers.

“Amazon is certainly worried about Shein, too,” Bai reckoned. “Once Shein has traffic, its next step may be to open its door to third-party [sellers] just as Amazon did.”