We’re not digging into another IPO filing today. You can read all about AppLovin’s filing here, or ThredUp’s document here.

This morning, instead, we’re talking about an old favorite: software valuations. The folks over at Battery Ventures have compiled a lengthy dive into the 2020 software market that’s worth our time — you can read along here; I’ll provide page numbers as we go — because it helps explain some software valuations.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money. Read it every morning on Extra Crunch, or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

There’s little doubt that there is some froth in the software market, but it may not be where you think it is.

The Battery report has a lot of data points that we’ll also work through in this week’s newsletter, but this morning, let’s narrow ourselves to thinking about rising aggregate software multiples, the breakdown of multiples expansion through the lens of relative growth rates, and cap it off with a nibble on the importance, or lack thereof, of cash flow margins for the valuation of high-growth software companies.

We’ll look at the changing public market perspective, and then ask ourselves if the aggregate image that appears is good or not good for software startups.

We’ll look at the changing public market perspective, and then ask ourselves if the aggregate image that appears is good or not good for software startups.

I chatted through pieces of the report with its authors, Battery’s Brandon Gleklen and Neeraj Agrawal. So, we’ll lean on their perspective a little as we go to help us move quickly. This is our Friday treat. Or at least mine. Let’s get into it.

Rising multiples

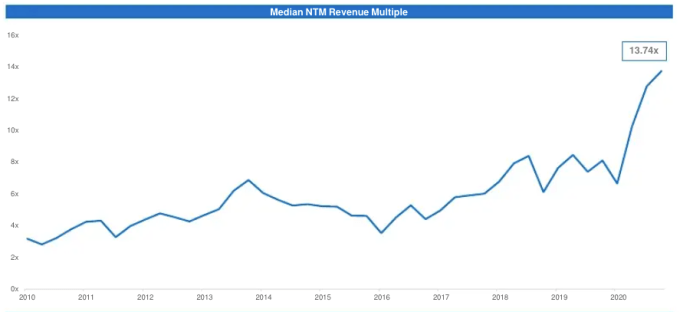

Let’s start with an affirmation. Yes, software valuations have risen to record-high multiples in recent years. Here’s the Battery chart that makes the change clear:

Page 31, Battery report. Image Credits: Battery Ventures

All this chart is good for is confirming what we expected. What matters is what comes next. To unpack the aggregate chart, let’s break it into three cohorts. Namely, low-growth companies (15% yearly growth and less), middle-growth companies (15%-30% yearly growth), and high-growth companies (30% or greater yearly growth).

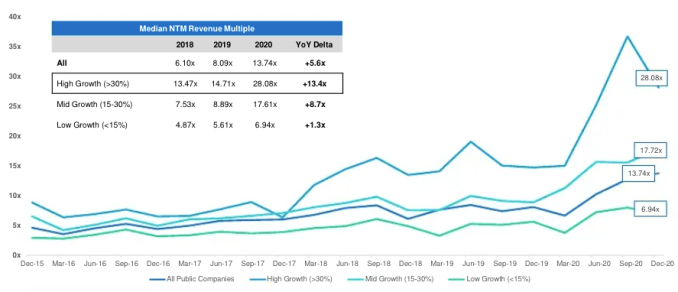

Here’s what the same data looks like when exploded into those groups:

Battery report, page 33. Image Credits: Battery Ventures

The chart quickly tells you that higher-growth software companies have seen the greatest multiples expansion through the end of 2020, but what’s notable is that all groups have seen regular bumps to their value. Indeed, the table makes it clear that each category has seen its multiples rise in both 2019 and 2020, for example.

How fair it is to have a general software valuation melt-up is up to you. However, Battery’s Agrawal explained to TechCrunch that growth rates can de-risk valuation multiples. The idea makes sense; the faster a company can grow, there’s less chance it suffers from a massive valuation decline if software revenue multiples ease in aggregate.

So the fastest-growing software companies, which have not coincidentally seen the greatest multiples expansion, are not the most risky. Which cohort is? Agrawal thinks that the most market froth can be in the middle-tier companies, which have seen strong multiples appreciation but aren’t growing as fast as the top tier; growth compounds, so a 20% growth rate is a thousand miles from a 30% pace.

This perspective fits neatly into a bullish argument regarding software valuations that I’ve heard from a few founders and VCs. It goes like this: The software market is bigger than most folks anticipated back when SaaS multiples were lower. But the software total addressable market (TAM) is proving to be so very large that SaaS companies have many more years of growth ahead of them than initially expected.

That point becomes even more acute among the fastest-growing software companies because they may be able to keep up strong growth rates for some time. So their value is lots. Thus, they trade at a premium today as investors are making a wager on what could be a very long run of top-line expansion and future profits.

But if the argument is applied to lesser companies, boosting their valuations with similar vigor, the more moderate growers — say from 15% to 30% growth — may not be able to live up to their valuations. So! The 8.89x to 17.61x SaaS multiple doubling that we saw in 2020 for the middle cohort of the SaaS market could be a warning sign of in-market exuberance that isn’t grounded in future results.

There could be some air to let from modern software companies of all growth profiles. We are at a local maximum for software multiples, Agrawal told TechCrunch.

How can we tell which companies might be a bit pricey, or more fairly valued? Notably, it doesn’t appear to be a question of profits. The market today is still somewhat focused on the growth side of things.

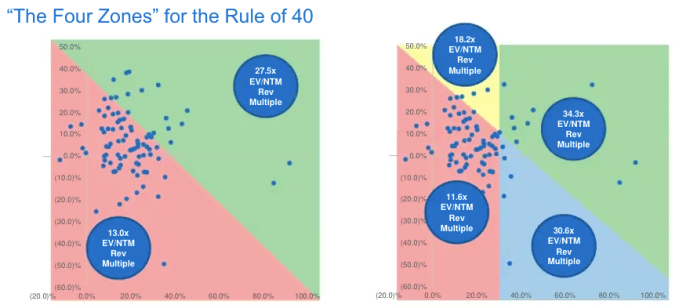

We need one more slide to understand where software stood at the end of 2020:

Battery report, page 36. Image Credits: Battery Ventures

This helps some. Battery explains it in the following manner:

Companies that exceed the “Rule of 40” trade at a higher revenue multiple (left chart: 27.5x NTM revenue versus 13.0x NTM revenue), BUT companies that exceed the “Rule of 40” AND are growing NTM revenues 30%+ trade at a premium (right chart: 34.3x NTM revenue)

Translating that into something closer to conversational English, the Rule of 40 is holding up as a rule of thumb, with a notable twist.

The Rule of 40 states that healthy software companies can add their growth (in percentage terms) to their profitability (as a percent of revenue) and get a number of 40 or greater. What the venture firm noted above is that companies that meet the Rule of 40 do trade for better multiples than those that do not, and that, among the group passing the Rule of 40, those that have a bias toward growth are worth even more.

This echoes the point we saw in our previous charts regarding the valuation differential between different growth cohorts of SaaS. Or as Battery put in its report, “public markets have shifted back to rewarding growth > growth + profitability.”

Yep. So it’s risk-on in the SaaS world today to a degree that should help keep public software valuations elevated for some time. For startups, this is all very good news. A rebiasing of investor sentiment toward growth over profits is great for high-growth, cash-burning startups. They tend to have lots of growth, and scarce profits.

More from the report soon, including notes from Gleklen, but we’re up against our loose limit of 1,000 words. Happy Friday!