Language learning apps, like many educational technology platforms, soared when millions of students went home in response to safety concerns from the coronavirus pandemic. It makes sense: Everyone became an online learner in some capacity, and for non-frontline workers, each day became an opportunity to squeeze in a new skill (beyond sourdough).

So why not learn a new language in a low-lift way?

Language learning platforms, including Babbel, Drops and Duolingo, all have benefitted from quarantine boredom as shown by surges in their usage. However, success also depends on whether these same companies can turn that primetime interest into dollars and profit.

To figure out if the language learning boom comes with paying customers, I caught up with Luis von Ahn, the CEO of Duolingo, a popular language learning company valued at $1.5 billion.

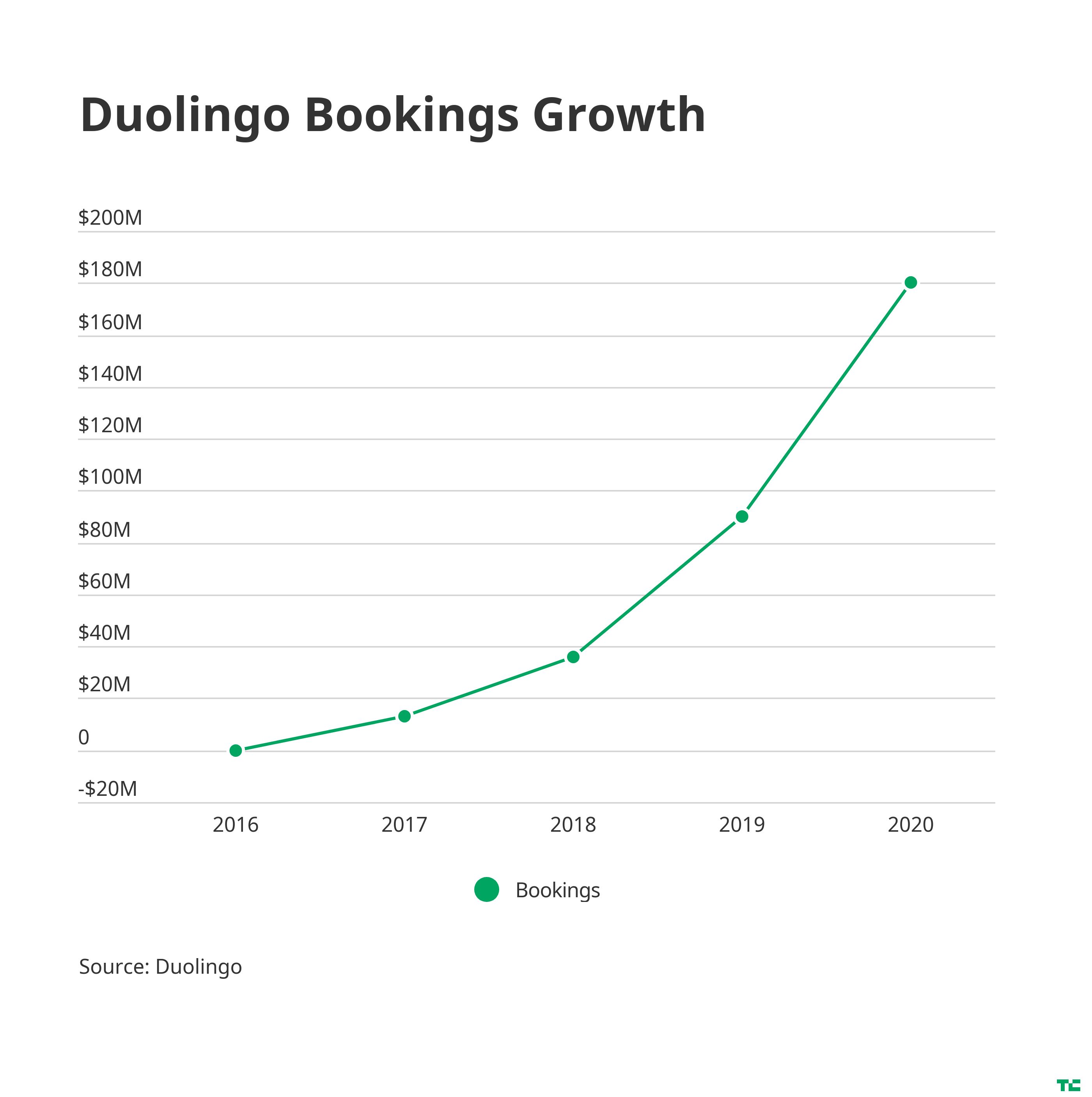

Von Ahn tells TechCrunch that Duolingo has hit 42 million monthly active users, up from 30 million in December 2019. The surge comes as new users are spending more time on the app in aggregate, for some of the reasons explained above. Duolingo has been steadily increasing in bookings over the past few years:

This year, Duolingo will hit $180 million in bookings, von Ahn estimates. The company discloses bookings as a proxy for revenue, because when someone purchases a subscription the app it is considered a “booking” until the completion of the subscription, when it becomes revenue.

“We’re more than breaking even,” von Ahn told TechCrunch.

While this growth is impressive, the most staggering metric that von Ahn revealed is that $180 million in bookings is only coming from 3% of its current users.

“Only 3% of our users pay us, yet we make more money than the apps where 100% of their users pay them,” he said.

Duolingo’s monetization strategy is unique enough that 97% of its users can use it for free. As my colleague Frederic Lardinois pointed out in 2017, Duolingo originally wanted to make money by making its free language learners translate text for paying customers. After that idea flopped, the company used advertisements and allowed paying customers to opt out of those advertisements.

The strategy is working for Duolingo, and the CEO says that they are looking to increase the 3% by expanding to more countries.

“If you’re in a wealthy country and you have an iPhone 11 and you use Duolingo a lot, I don’t feel bad charging you,” he said. “But if you have a low-end device in India, I don’t particularly want to charge you.” He added that the goal is never to get to 100% paying customers, noting that it’s important for the service to remain free for accessibility.

While Duolingo is currently a cash-flow positive company, that was not always the case. In 2016, von Ahn wrote that Duolingo spends $46,000 a day to keep up with servers and employee salaries. The price tag only increases as they scale in user growth and employee count. While Duolingo confirmed that this was true, they declined to share how much they are currently spending.

In April, Duolingo raised $10 million in a secondary transaction and equity financing to bring on General Atlantic, an investment firm with a global footprint.

Part of that check is earmarked toward scaling another one of its monetization features, the English certification test. To be clear, the revenue brought in from the English test is separate from the $180 million booking rate brought in by language learning premium subscribers. Duolingo did not share how much revenue the English learning test is bringing in, but did point to how it is having a 1500% global year-over-year growth in test takers.

The test is supported by over 2,500 institutions and costs $49 to take.

The English test business is big, lucrative and not lonely. The test is needed for non-native English speakers to prove their proficiency needed for employment and schooling in the states.

Babbel, Duolingo’s Berlin-based competitor, similarly launched an English language test back in 2017. LinkedIn rolled out skills assessments, one of which focuses on English, in early 2019. The optionality is great, but can only be successful if schools take these tests as serious indicators of proficiency. Luckily for the services, the coronavirus shut down traditional in-person testing centers and made on-demand, virtual testing a necessary option.

Ultimately, von Ahn is optimistic about Duolingo’s future when the pandemic ends. China, he admits, decreased in usage when the reopening began, but since has resumed normal growth patterns.

Duolingo is targeting its energy toward continued gamification of its app, acquisition of other companies (they’ve met with 20 so far and aren’t yet impressed) and bulking out the English learning test. Von Ahn hopes to one day take the company to the public markets.

“We’re not selling,” he said. “That’s never happening.”