A survey of responses from more than 30 companies to questions about how they’re approaching EU-U.S. data transfers in the wake of a landmark ruling (aka Schrems II) by Europe’s top court in July, which struck down the flagship Privacy Shield over U.S. surveillance overreach, suggests most are doing the equivalent of burying their head in the sand and hoping the legal nightmare goes away.

European privacy rights group noyb has done most of the groundwork here — rounding up in this 45-page report responses (some in English, others in German) from EU entities of 33 companies to a set of questions about personal data transfers.

It sums up the answers to the questions about companies’ legal basis for transferring EU citizens’ data over the pond post-Schrems II as “astonishing” or AWOL — given some failed to send a response at all.

Tech companies polled on the issue run the alphabetic gamut from Apple to Zoom. Airbnb, Netflix and WhatsApp are among the companies that noyb says failed to respond about their EU-US data transfers.

Responses provided by companies that did respond appear to raise many more questions than they answer — with lots of question-dodging “boilerplate responses” in evidence and/or pointing to existing privacy policies in the hope that will make the questioner go away (hi Facebook!).

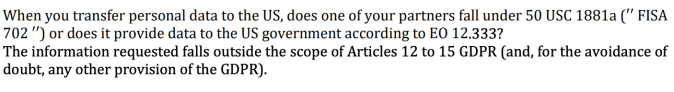

Facebook also made repeat claims that sought for info falls outside the scope of the EU’s data protection framework…

In addition, noyb highlights a response by Slack which said it does not “voluntarily” provide governments with access to data — which, as the privacy rights group points out, “does not answer the question of whether they are compelled to do so under surveillance laws such as FISA702”.

In addition, noyb highlights a response by Slack which said it does not “voluntarily” provide governments with access to data — which, as the privacy rights group points out, “does not answer the question of whether they are compelled to do so under surveillance laws such as FISA702”.

A similar issue affects Microsoft. So while the tech giant did at least respond specifically to each question it was asked, saying it’s relying on Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) for EU-U.S. data transfers, again it’s one of the companies subject to U.S. surveillance law — or as noyb notes: “explicitly named by the documents disclosed by Edward Snowden and publicly numbering the FISA702 requests by the US government it received and answered”.

That, in turn, raises questions about how Microsoft can claim to (legally) use SCCs if users’ data cannot be adequately protected from U.S. mass surveillance…

The Court of Justice of the EU made it clear that use of SCCs to take data outside the EU is contingent on a case by case assessment of whether the data will in fact be safe. If it is not, the data controller is legally required to suspend the transfer. EU regulators also have a clear duty to act to suspend transfers where data is at risk.

“Overall, we were astonished by how many companies were unable to provide little more than a boilerplate answer. It seems that most of the industry still does not have a plan as to how to move forward,” noyb adds.

In August the group filed 101 complaints against websites it had identified as still sending data to the U.S. via Google Analytics and/or Facebook Connect integrations — with, again, both tech giants clearly subject to U.S. surveillance laws, such as FISA 702.

And noyb founder Max Schrems — whose surname has become synonymous with questions over EU-U.S. data transfers — continues to push the Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC) to take enforcement action over Facebook’s use of SCCs in a case that dates back some seven years.

Earlier this month it emerged the DPC had written to Facebook — issuing a preliminary order to suspend transfers. However Facebook filed an appeal for a judicial review in the Irish courts and was granted a stay.

In an affidavit filed to the court, the tech giant appeared to claim it could shut down its service in Europe if the suspension order is enforced. But last week Facebook’s global VP and former U.K. deputy PM, Nick Clegg, denied it could shut down in Europe over the issue. Though, he warned of “profound effects” on scores of digital businesses if a way is not found by lawmakers on both sides of the pond to resolve the legal uncertainty around U.S. data transfers. (A Privacy Shield 2 has been mooted but the European Commission has warned there’s no quick fix, suggesting reform of U.S. surveillance law will be required.)

For his part, Schrems has suggested the solution for Facebook at least is to federate its service — splitting its infrastructure in two. But Thierry Breton, EU commissioner for the internal market, has also called for “European data…[to] be stored and processed in Europe” — arguing earlier this month this data “belong in Europe” and “there is nothing protectionist about this”, in a discussion that flowed from U.S. President Trump’s concerns about TikTok.

Back in Ireland, Facebook has complained to the courts that regulatory action over its EU-EU data transfers is being rushed (despite the complaint dating back to 2013); and also that it’s being unfairly singled out.

But now with data transfer complaints filed by noyb against scores of companies on the desk of every EU data supervisor, and regulators under explicit ECJ instruction, they have a duty to step in, as a lot of pressure is being exerted to actually enforce the law and uphold Europeans’ data rights.

The European Data Protection Board’s guidance on Schrems II — which Facebook had also claimed to be waiting for — also specifies that the ability to (legally) use SCCs to transfer data to the U.S. hinges on a data controller being able to offer a legal guarantee that “U.S. law does not impinge on the adequate level of protection” for the transferred data. So Facebook et al would do well to lobby the U.S. government on reform of FISA.