Welcome back to Tech at Work, where we look at labor, diversity and inclusion. Given the amount of activity in this space, we’re going to ramp this up from bi-weekly to weekly.

This week, we’re looking at the latest action from a group of Amazon warehouse workers in the San Francisco Bay Area, how to avoid Genderify’s massive algorithmic bias fail and the rise of the use of BIPOC, which stands for Black, Indigenous and people of color, and how to properly use the term.

Stay woke

Amazon warehouse workers stage sunrise action

Amazon delivery drivers in the San Francisco Bay Area are kicking off the month by protesting the e-commerce giant’s labor practices related to the COVID-19 pandemic. As part of a caravan, workers plan to head to Amazon’s San Leandro warehouse this morning to pressure the company to shut down the facility for a thorough cleaning.

“They are having COVID cases reported and they’re not being truthful about how many, and they’re not being reported right away,” Amazon worker Adrienne Williams told TechCrunch. “We’re seeing this pattern of Amazon finding out and then not telling people for two weeks so they don’t have to pay anyone.”

In a statement to TechCrunch, Amazon said:

Nothing is more important than health and well-being of our employees, and we are doing everything we can to keep them as safe as possible. We’ve invested over $800 million in the first half of this year implementing 150 significant process changes on COVID-19 safety measures by purchasing items like masks, hand sanitizer, thermal cameras, thermometers, sanitizing wipes, gloves, additional handwashing stations, and adding disinfectant spraying in buildings, procuring COVID testing supplies, and additional janitorial teams.

In addition to shutting down the warehouse for sanitizing, workers are asking for better communication.

“The drivers have no idea if there are ever any cases because we don’t have access to the internal warehouse A to Z communications they have,” Williams, who works at the Richmond warehouse, said. “So we never get the alerts if there are COVID cases. We’re not on that internal communication but we go in those warehouses twice a day to get our shifts and packages.”

Because drivers are generally employed by delivery service partners, Amazon says it does not have direct communication with them. However, Amazon says it immediately notifies the delivery service partner who then communicates with the drivers.

By staging the action so early, the hope is to prevent workers from being able to load delivery vehicles, Williams said.

“If the vans are left in the warehouse, Jeff Bezos takes the financial hit,” she said. “Halting deliveries and keeping them in the warehouse means Amazon gets hit with the bill.”

Lesson for startups: Treat all of your workers with dignity and respect.

Genderify epitomizes algorithmic bias

Genderify, an AI-powered gender identification tool designed for marketing purposes, had a very short-lived life. After launching on Product Hunt earlier this week, it quickly faced criticism for its heavily biased responses. That’s because Genderify was a perfect example of what happens when bad algorithms are applied at scale. Following the intense backlash and scrutiny, Genderify shut down.

Algorithms are sets of rules computers follow to solve problems and make decisions. Whether it’s the information people see about us, the jobs we get hired to do, the credit cards we get approved for and, down the road, driverless cars that either see us or don’t see us, algorithms are increasingly becoming a big part of our lives.

But there is an inherent problem with algorithms that begins at the most base level and persists throughout its adaption: human bias that is baked into these machine-based decision-makers.

When developing your startup, it’s important to think about the human biases your algorithm may be perpetuating. As they say, garbage data in, garbage data out.

On language

Unpacking “BIPOC”

I recently read an article that explored the rise of the BIPOC acronym and the complications associated with its definition, which includes Black, Indigenous and people of color. What led me to read it was a conversation I had with my white girlfriend about the meaning of the term and when and how to apply it. I couldn’t even tell you what either of us said, because I genuinely don’t remember, but I can tell you what I felt. I felt shame — shame for not being able to articulate what it means and for not being able to discuss its origins as a Black woman. There were several parts that jumped out at me, but this part really jumped out at me, because it is me:

There’s this anxiety over saying the wrong thing,” says deandre miles-hercules, a PhD linguistics student who focuses on sociocultural linguistic research on race, gender, and sexuality. “And so instead of maybe doing a little research, understanding the history and the different semantic valences of a particular term to decide for yourself, or to understand the appropriateness of a use in a particular context, people generally go, ‘Tell me the word, and I will use the word.’ They’re not interested in learning things about the history of the term, or the context in which it’s appropriate.

Before that conversation with my girlfriend, I had a general understanding that using “BIPOC” instead of “POC” was a way to center Black and Indigenous folks, as well as acknowledge the unique experiences of Black (slavery) and Indigenous (genocide, theft of land) folks in the U.S. But beyond that, I wasn’t super interested in further exploration of the term and its origins.

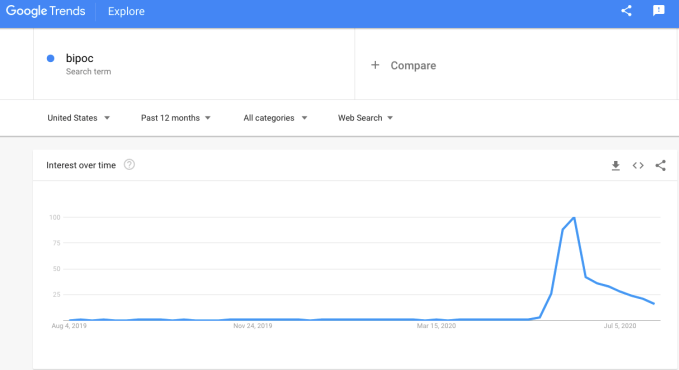

Searches for BIPOC hit its peak around June 7, according to Google Trends, which perhaps speaks to the increased usage of the term as well as lack of clarity around what it means.

While I understood the intention to center Black and Indigenous folks with BIPOC, I hadn’t thought about how the term can simultaneously blur the differences between the experiences of Black and Indigenous people — something Stanford sociocultural and linguistic anthropologist Jonathan Rosa discusses in the Vox article. He points out how the U.S. has historically determined who is allowed to identify as Black and Indigenous. The one-drop rule, which dates back as far as 1622 and was adopted as law in the 20th century, defined someone as Black if they just had even the tiniest amount of African ancestry. As Rosa said:

What that ends up doing is maximizing the Black population in the United States. Why would the Black population in the United States be constructed in that way? Well, if that population is enslaved, then you can see why that logic would prevail.

On the flip side, the U.S. tries to minimize the number of people who can identify as Indigenous. According to Rosa:

If foundational to the United States is the logic of Manifest Destiny, and the idea that this is ‘virgin territory,’ then there are no Indigenous people in the United States, or there were very few, and there was no mass genocide. By minimizing the Indigenous in the United States, you end up legitimizing the idea of the United States as this territory that was discovered and was uninhabited.

It’s all very interesting and I thought it was worth sharing. You can read more over on Vox.

My point in discussing this here is to encourage folks to do what I’ve only recently done: learn more about the term and think about why and how I use it. Language is a powerful tool, and as we see more tech companies using BIPOC in their corporate-speak, it’s worth understanding the complexities of the term. And if you’re using it in your startup communications, think about why you’re doing it. Is it just because everyone else is doing it? Let’s hope not.