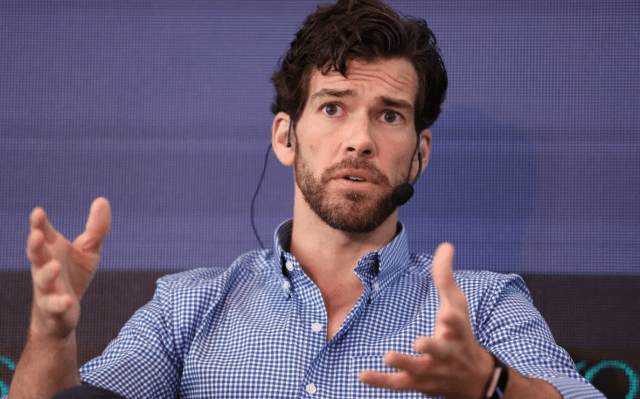

Last week, we interviewed Brendan Wallace, a real estate-focused venture capitalist whose portfolio companies include Opendoor, which buys and sell homes, and scooter company Lime, which helps building owners navigate around parking requirements by installing docking stations instead.

We first talked with Wallace almost exactly three years ago when he and partner Brad Greiwe took the wraps off their venture firm Fifth Wall Ventures and its $212 million debut fund. What really stood out to us at the time is that it was backed by a long list of real estate heavyweights. They’re understandably eager to get a peek at up-and-coming technologies and, in some cases, deploy them.

Wallace and Greiwe have been awfully busy since that initial conversation. Last year, they closed a second flagship fund with $503 million in capital commitments. Fifth Wall is also working to close two other funds, including a $200 million retail fund focused on matching online brands with real-world real estate and a reported $200 million carbon impact fund whose capital will enable its limited partners to expressly invest in sustainable technology.

Wallace declined to discuss the last two funds, presumably owing to SEC regulations, but he did talk with us about what he says is the biggest thing to shake up the real estate industry in “the last five decades.” We also chatted about how the coronavirus impacted a recent fundraising trip to Singapore and how WeWork’s public retrenching has affected how investors feel about real estate startups right now (he suggests WeWork’s fall definitely made an impression). Some excerpts from our conversation follow, edited lightly for length and clarity.

TechCrunch: We’d read that you were recently in Singapore meeting with new investors.

Brendan Wallace: Yes, I was in Singapore meeting with our existing investors and it was a pretty unique time to be there. When I went, which was about two weeks ago, the outbreak of coronavirus was fairly contained in China. But then as you probably read, it spread pretty rapidly in Singapore, so at the moment, I’m actually kind of self-quarantining myself in my own house.

When did you arrive back in the U.S.?

I arrived back on Monday, [but] the unique feature of the virus is that certain people don’t actually show symptoms either for a long period or, in some cases, they’re not very material; they’re not very acute. Given that we have a large team, I’m trying to be extra-sensitive and thoughtful about, you know, not contaminating my whole office.

Was getting on a plane back to the U.S. at all problematic?

It wasn’t. I flew originally to Tokyo and there were people that were on a precautionary basis wearing face masks. And I did as well, but in some way, I thought that was almost overkill and unnecessary. But as I was in Japan and then subsequently went to Singapore, the numbers started to exponentially grow and so on the way back, I went through quite a number of temperature screenings; I had to wear a face mask literally at all times in Singapore. Face masks and hand disinfectant and sanitizer — I mean, you can’t even get your hands on them. They’re effectively trading on the black market. So it was a bit surreal to be there, but the country is still functioning perfectly well, and probably part of that comes from their experience with SARS. This is a country that was very much exposed to SARS earlier so I think they know how to live with this. I think here in America, people react a little more intensely to health scares.

You announced your first fund in 2017 just as proptech seemed to be coming on strong, dating back to 2015, 2016. Why the excitement around it just then?

Real estate represents 13% of U.S. GDP. It’s the largest asset class, it’s the largest lending category. And I think anyone who is even familiar with the real estate industry knows that it is one of the least technologized industries. And so what we saw starting around 2015 was almost an age of enlightenment where real estate CEOs recognized they needed to have a forward stance on technology, both offensively to identify technologies that could enhance their business, but also defensively to be aware of potential disruptive threats.

You had recreational venture capital happening where corporate, real estate [and] owner-operator developers were dabbling in venture, but there was no institutional capital in the space.

It did seem that WeWork also caught a lot of people’s attention; it made real estate tech sort of sexy. Has its very public stumble impacted the space at all? Has it attracted skepticism?

It’s a great question because WeWork was this company that achieved a valuation that I think everyone was scratching their heads at and that came back to Earth very suddenly.

So a few things about WeWork. First, it really wasn’t an innovative business model whatsoever. The business of master leasing space and then chopping that space up, densifying it and subleasing it has been done for decades. So it was puzzling from our perspective when… WeWork commanded so such attention and brand equity from the venture community [yet] we were hearing real estate owners say, “we’ve seen this movie before, we know how it ends — it ends badly. I don’t understand why this company is raising so much money.”

What WeWork caught was the secular tailwind of what is broadly called “flex office,” [meaning that instead of] leasing space for five or 10 years, [landlords are] giving tenants more flexible access to space, shorter-term leases, more flexibility in those leases, more open seating plans… Flex office represents about 1% of the U.S. office market and most estimates have it growing to about 10% or more over the next decade, so we’re talking about a massive increase, and WeWork was at the cutting edge of that. But their business model was not really unique.

You funded a company that is similar, though. Industrious.

Industrious is actually quite different than WeWork. Even though they’re oftentimes lumped together, they have radically different business models. Industrious [operates a] master lease model, [wherein] you actually just manage, operate and market the space on behalf of real estate owners. You don’t take on any long-term liabilities. The [model] means is it doesn’t grow quite as fast, but it also has a much more stable relationship with the landlord because the landlord wants them in there to actually manage their space.

I do think WeWork’s demise has changed sentiment for real estate tech broadly, but it feels a little bit out of sync with the reality of frankly, how well many of the companies and real estate tech are doing.

How do you define your mandate? Is construction tech its own ball of wax?

The way we define our mandate is any technology that can be strategic to the real estate industry. Definitionally, it includes everything that you think of as proptech, so companies like VTS, which provides commercial property owners online tools for managing leases. Then as you kind of venture out from there, you can look at real estate-related fintech, so [we’re investors in] Opendoor and Blend in the mortgage technology space, and Hippo in the digital home insurance space, and States Title in the title insurance space.

We’ve also made a lot of investments around data analytics, security and facial recognition, because all of those things are hugely impactful to the real estate industry.

A more extreme example of where the periphery of that mandate lies is our investment in Lime, the scooter company, which clearly does not seem like real estate tech. But when you look at that business, a huge part of it depends on distribution to where consumers are, which is real estate assets and establishing charging and docking stations at those assets. There is a huge real estate dependency to the scooter business [because you need a] network of charging stations, you need to structure relationships and deals with landlords and you also need to be able to deliver these devices in an organized way at these consumer endpoints at malls, office buildings and multi-family buildings.

What is the impetus for this new carbon impact fund? To help your partners address new regulations? Is there a moral imperative?

I cannot talk about the funds specifically. But what I can talk about is how real estate owners are looking at sustainability, technology and green tech broadly. It wasn’t an area that the real estate industry previously focused on, but what you’ve seen in the last three years is this convergence of forces around sustainability for the real estate industry.

The first is just public attention. Obviously, the climate crisis has become increasingly topical. It’s kind of front-and-center to almost every geopolitical conversation that’s being had right now. So I think that is escalating. I think part and parcel to that, the real estate industry hadn’t really had a spotlight shone on it with respect to its environmental impact [and] — the real estate industry is responsible for 40% of all energy consumption, 30% of all greenhouse gases and 40% of all raw materials.

What’s also happened around this kind of public side of it, is that really forward-looking, progressive tenants of space like Google or Netflix, they’re going to landlords and saying, “we won’t lease space in your asset unless you conform to new, much more stringent environmental standards.” So it’s actually affecting the demand for real estate.

There’s a second bucket, which is the capital market side of it. Large pension funds and buyers of REIT stock and real estate lenders have said, “we will preferentially deploy capital to low- or no-carbon impact real estate.” And so there’s actually a cost-of-capital advantage for real estate owners who are building more sustainable assets, and that doesn’t even take into account the fact that insurance costs are obviously lower for more sustainable assets.

The last one is really when the pin dropped, and it happened last year. Obviously, Trump previously pulled out of the Paris Climate accord. But what local jurisdictions did was put their cities back in it; they applied the Paris standards to cities. And so in New York — it was the first city to do so — they enacted a carbon neutrality law that basically says all commercial real estate assets need to be carbon-neutral by 2030. And there’s a series of sliding scales, but you effectively start paying fines as early as 2024.

The same is actually now true roughly in Los Angeles. So the government just stepped in and said real estate owners need to be carbon-neutral; you asked the question from the perspective of a moral imperative. And I think that absolutely there’s an element of altruism, there’s an element of protecting our future. But I actually think the true driver of it right now is a financial imperative for real estate investors.

Make no mistake; we are front-and-center to what is happening in the real estate industry and the collision with technology, and this is the single-most-important thing that has happened to the real estate industry in the last five decades. The real estate industry is going to have to go carbon-neutral and that is brand-new.