Electric scooter operator Skip is gearing up to appeal San Francisco’s decision to deny the company a permit to operate in the city. When the Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA) announced the permit grantees in September, it came as a surprise to Skip, which had previously received a permit to operate as part of the city’s pilot program.

Ahead of the appeal hearing, TechCrunch caught up with Skip CEO Sanjay Dastoor to learn about the company’s game plan and why he thinks it can prevail in a battle that other electric scooter providers have lost.

Prior to the city’s decision last year to grant permits to Lime, Uber’s JUMP, Bird’s Scoot and Ford’s Spin, Skip was one of only two companies operating shared electric scooter services in San Francisco. Leading up to the new permitting application process, Skip said it had been working to ensure its electronic locks would be fully integrated by the beginning of the new permit period, Dastoor told TechCrunch. The company did this with guidance from the SFMTA, so when Skip was denied a permit, the team was caught off guard.

“It was a huge surprise,” Dastoor said. “We found out basically the same time as the press did that we didn’t get that permit, so it was pretty surprising to all of us.”

According to the city, the decision came down to Skip receiving an average score below the required threshold of 2 in the Device Standards & Safety Assurances section. It’s worth noting that prior to the evaluation in June, Skip grounded its fleets in both Washington, D.C. and San Francisco after a scooter caught fire in D.C. But Dastoor says the decision by the city seemed to come down to a formatting issue, Dastoor said.

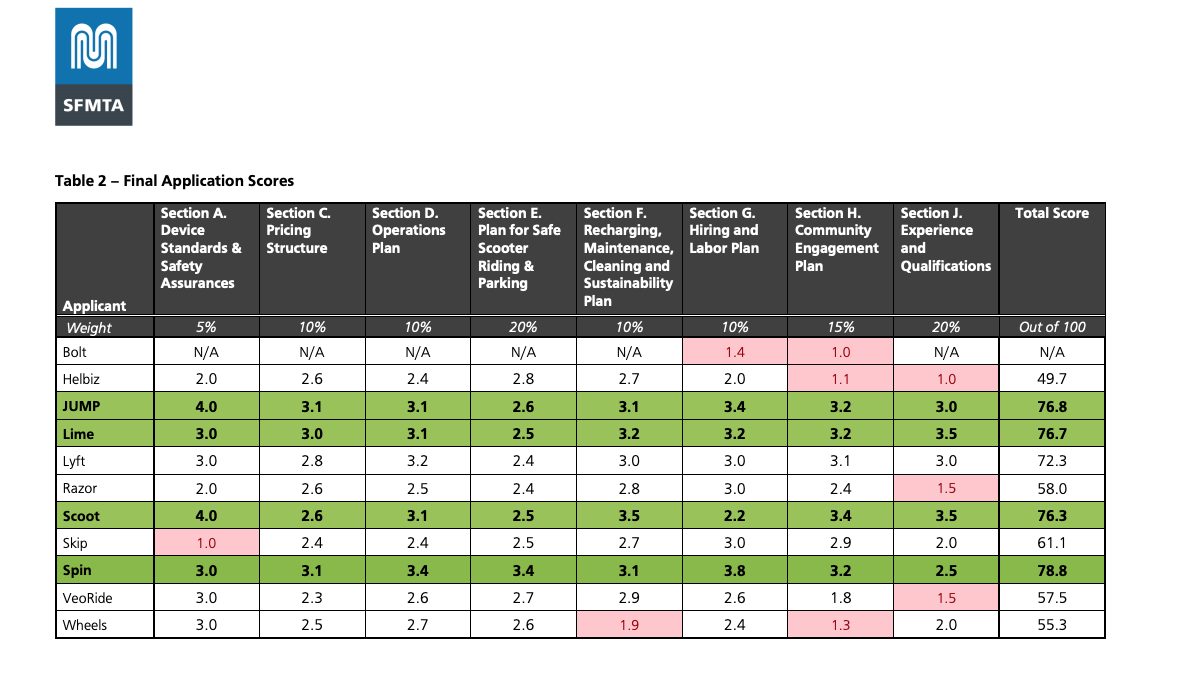

Below, you can see Skip received a low score of 1 in Section A, which led the SFMTA to disqualify Skip from further evaluation.

“We received the lowest score of any operator in device safety, based on what we feel is a formatting issue where we didn’t have letter A, number three in our application, even though all that information was throughout the application,” Dastoor said. “We have a very good track record on device safety and what we feel like is the industry’s best practices around that, which we described very carefully.”

That section specifically asked about device certifications and what operators would do if there was an issue with a scooter. Throughout the application, Skip said it included information pertaining to the need to hire employees (rather than contractors) to do safety inspections, its software and hardware system built to do continuous monitoring, procedures with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, recertifications and more, Dastoor said.

“We talked about all of the steps we do, but the way the application was structured, a lot of it was in the operations plan section or the hiring and training sections,” Dastoor said. “So it was all in there but not in Section A. You know, the application said, ‘look, you’re strongly encouraged to follow that,’ but it doesn’t say you’re required to. So we wrote this in a way that we felt addressed it in a very logical way.”

As a result of not receiving a permit, Skip was forced to lay off 34 employees and close its maintenance and repair shop in San Francisco. When I met with Skip in August, ahead of the city’s decision, Dastoor felt confident the company would be able to deploy its custom-built electric scooters in San Francisco that coming October.

But many companies, including Lime, Spin and Uber, have previously tried to appeal the city’s permitting decisions relating to electric scooters. None, however, have been successful in their efforts. Dastoor seems optimistic that the process will go a bit differently for Skip.

“If you look at how these appeals have gone in the past, it’s often been saying, ‘look, there’s judgment and discretion by the SFMTA, by the director, by the staff to choose who they feel are the right folks to operate based on the proposals they put forward,’ ” Dastorr said. “And so a lot of those appeals last year were saying, ‘look, we think we should be allowed to operate for X,Y and Z reasons,’ ” he added. “In our case, we were disqualified from even being considered. A big portion of our argument will be, it’s completely fair for us to be disqualified for something that was required that we didn’t do, even if that may be inconsistently applied. But if it’s encouraged to do and we’re disqualified, and that results in the lowest possible score, when we feel like we have the best industry-leading standard here, we think that’s something that needs to be addressed.”

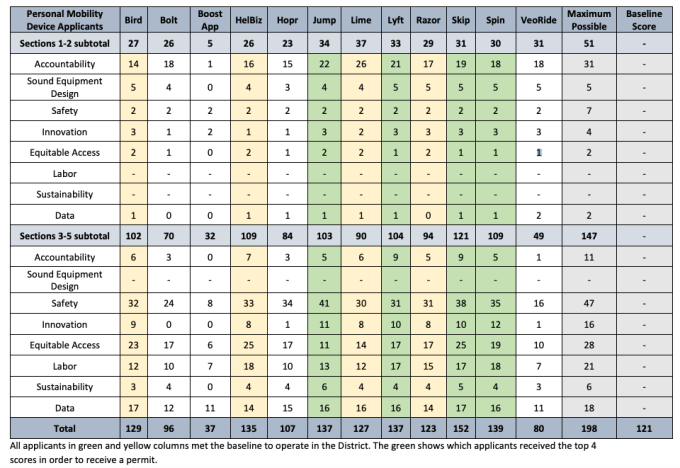

Over in Washington, D.C., where Skip currently operates the majority of its vehicles, the company scored the highest of any scooter operator in the permitting process. Of a maximum possible score of 198, Skip scored 152.

“I don’t want to say D.C. is better because we, you know, scored higher or something, but we created the first permanent program in the country in D.C., even though we were based in San Francisco,” Dastoor said. “We chose to do it there because we wanted to do this the right way — working with regulators. So it was very surprising to us that San Francisco felt like we were one of the least-qualified applicants to operate in San Francisco or that we had the worst score for safety. Those were both very surprising to us and not something we saw reflected in other cities, like D.C.’s evaluation of Skip.”

The best-case scenario for Skip is that the appeals hearing officer sides with Skip and allows the company to operate again in San Francisco. If that happens, Skip would try to hire back the people it had to let go or try to rebuild the team with new recruits. If the appeal is denied, the plan would be to evaluate the options the company has left. One option is to simply wait until the next permit cycle reopens later this year.

“But either way, we’re hoping and going to be pushing to be back in San Francisco this year,” Dastoor said.

Ultimately, San Francisco is an important market for Skip. For one, based on data from its year of operating here, ridership is pretty comparable with D.C. Both areas present prime opportunities for electric scooters due to size, integration with public transit services, traffic congestion and other factors.

“San Francisco, like D.C., is a major dense, crowded city with not a perfect set of solutions for transportation,” Dastoor said. “So obviously scooters can be a big part of that. And we’re focused on the problems of the largest cities, like SF and D.C., that are going to be opening up in the next 12 to 24 months, like New York and Seattle.”

Compared to Bird and Lime, Skip’s presence is much smaller. But that’s all by design, Dastoor said.

“Our philosophy on this has always been that the success of the system depends a lot on the hardware, and how the hardware and software work together,” Dastoor said. “We believe that scaling the business without a vehicle that’s environmentally sustainable and without predictable behavior, it’s harder than if you’re starting with that vehicle and then scaling up. What we’re seeing from the largest cities, like Paris for example, a lot of their scoring is based on environmental impact and safety. We think the big cities care about the same things we do. So, our approach is get it right before you scale.”