In African fintech, the fourth quarter of 2019 brought big money to new entrants.

Chinese investors put $220 million into OPay and PalmPay — two fledgling startups with plans to scale in Nigeria and the broader continent. Several sources told me the big bucks had created anxiety for more than few payments ventures in Nigeria with similar strategies and smaller coffers. They may not need to fret just yet, however: lessons from Africa’s most successful mobile-money case study, M-Pesa, suggest that VC alone won’t buy scale in digital finance.

Startups and fintech in Africa

Over the last decade, Africa has been in the midst of a startup boom accompanied by big growth in VC and improvements in internet and mobile penetration.

Some definitive country centers for company formation, tech hubs and investment have emerged; Nigeria, South Africa and Kenya lead the continent in numbers for all those categories. Additional strong and emerging points for innovation and startups across Africa’s 54 countries and 1.2 billion people include Ghana, Tanzania, Ethiopia, and Senegal.

The continent surpassed $1 billion in VC to startups in 2018 and per research done by Partech and WeeTracker, fintech is the focus of the bulk of capital and deal-flow.

By several estimates, Africa is home to the largest share of the world’s unbanked and underbanked population.

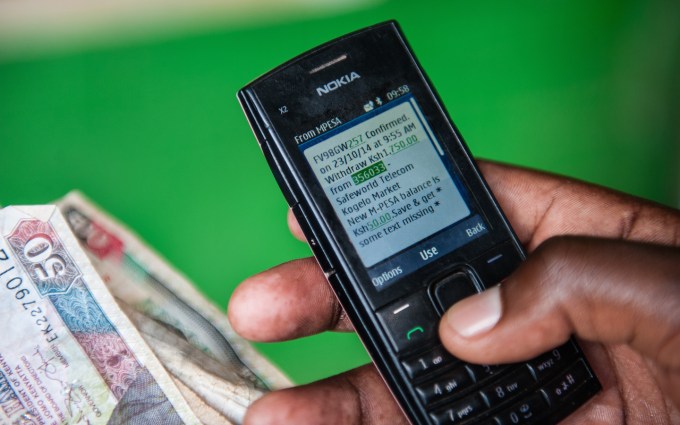

This runs parallel to the region’s off-the-grid SME’s and economic activity — on display and in commercial motion through the street traders, roadside kiosks and open-air markets common from Nairobi to Lagos.

IMF estimates have pegged Africa’s informal economy as one of the largest in the world. Thousands of fintech startups have descended onto this large pool of unbanked and underbranked citizens and SMEs looking to grow digital finance products and market share.

In this race, the West African nation of Nigeria — home to Africa’s largest economy and population — is becoming an epicenter for VC. Many fintech-related companies are adopting a strategy of scaling there first before expanding outward.

Enter PalmPay and OPay

That includes new entrants OPay and PalmPay, which raised so much capital in fourth quarter 2019. It’s notable that both were founded in 2019 and largely incubated by Chinese actors.

PalmPay, a consumer-oriented payments product, went live in November with a $40 million seed-round (one of the largest in Africa in 2019) led by Africa’s biggest mobile-phones seller — China’s Transsion. The startup was upfront about its ambitions, stating its goals to become “Africa’s largest financial services platform,” in a company statement.

To that end, PalmPay conveniently entered a strategic partnership with its lead investor. The startup’s payment app will come pre-installed on Transsion’s mobile device brands, such as Tecno, in Africa — for an estimated reach of 20 million phones in 2020.

To that end, PalmPay conveniently entered a strategic partnership with its lead investor. The startup’s payment app will come pre-installed on Transsion’s mobile device brands, such as Tecno, in Africa — for an estimated reach of 20 million phones in 2020.

PalmPay also launched in Ghana in November and its U.K. and Africa-based CEO, Greg Reeve, confirmed plans to expand to additional African countries in 2020.

If PalmPay’s $40 million seed round got founders’ attention, OPay’s $120 million Series B created shock-waves, coming just months after the mobile-based fintech venture raised $50 million — making OPay’s $170 million capital haul equivalent to roughly a fifth of all VC raised in Africa in 2018.

Founded by Chinese owned consumer internet company Opera — and backed by 9 Chinese investors — OPay is the payment utility for a suite of Opera-developed internet based commercial products in Nigeria that include ride-hail apps ORide and OCar and food delivery service OFood.

With its latest Series A, OPay announced it would expand in Kenya, South Africa, and Ghana.

In Nigeria, OPay’s $170 million Series A and B announced in the span of months dwarfs just about anything raised by new and existing fintech players, with the exception of Interswitch.

The homegrown payments processing company — which pioneered much of Nigeria’s digital finance infrastructure — reached unicorn status in November when Visa took a reported $200 million minority stake in the venture.

A sampling of more common funding amounts for payments ventures in Nigeria includes established fintech company Paga’s $10 million Series B. Recent market entrant Chipper Cash’s May 2019 seed-round was $2.4 million.

There is a large disparity between fintech startups in Nigeria with capital raises in ones and tens of millions vs. OPay and PalmPay’s $40 and $120 million rounds. Conventional wisdom could be that the big-capital, big spending firms have an unmistakable advantage in scaling digital payments in Nigeria and other markets.

A look at Kenya’s M-Pesa may prove otherwise.

M-Pesa

After participating in dozens of African fintech discussions, I’ve discovered M-Pesa is that product story that people are either tired of hearing about — or have never heard of. Developed by Kenya’s largest telco Safaricom, and its stakeholder Vodaphone, M-Pesa launched in 2007 as a basic P2P mobile-money app operable on simple USSD and feature phones.

It was created to solve a basic need of Kenyan citizens to transfer money conveniently and safely around the country, which lacked a strong retail banking presence.

Prior to M-Pesa, Kenyans commonly gave money-filled sacks to bus drivers who delivered funds throughout the East African country of 50 million, late Safaricom CEO Bob Collymore explained to me years ago.

M-Pesa went on to become widely popular in Kenya — a go-to global case-study on digital finance — and one of the most profitable mobile-money products in the world.

Safaricom’s product still holds remarkable dominance in Kenya, Africa’s 6th largest economy. M-Pesa has 20.5 million customers across a network of 176,000 agents and generates around one-fourth ($531 million) of Safaricom’s ≈ $2.2 billion annual revenues (2018).

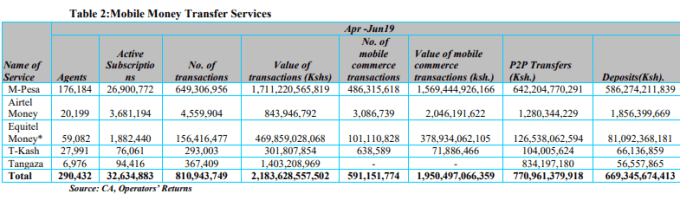

M-PESA Sector Stats 4Q 2019 per Kenya’s Communications Authority

Compared to other players — such as Airtel Money and Equitel Money — M-Pesa has 80% of Kenya’s mobile money agent network, 82% of the country’s active mobile-money subscribers and transfers 80% of Kenya’s mobile-money transactions, per the latest sector statistics.

Product positioning

Safaricom’s M-Pesa is frequently lauded as an African innovation story, but it’s just as much a regulatory and brand-positioning success story.

On the regulation side, the mobile-money product — which means M-Money in Kenya’s national language of Swahili — was developed in the wake of reforms that privatized and broke up a state monopoly in Kenya’s telecoms sector.

M-Pesa also received a boost from Kenya’s Central Bank in 2007, when it determined the product would not require a traditional banking license to operate. This allowed Safaricom to go to market quickly and grow its mobile-money platform unhindered by legacy banking rules.

Just as significant as M-Pesa’s technology and use case was Safaricom’s skillful marketing program and product positioning, which was tailored superbly to Kenyan consumers. M-Pesa has become a model study of aligning a product to a market — from its name, branding, price points, agent network and advertising, it’s one of those products — like the iPhone or the Volkswagen beetle — that got it all right to connect strongly to Kenyan consumers.

Lessons from M-Pesa

So what lessons does M-Pesa’s rise hold for Africa’s new big-money fintech entrants OPay and PalmPay?

The first could be to pay attention to the operability of their products and business models across multiple regulatory environments in Africa. Nigeria’s Central Bank conducted a lengthy review of digital finance regulations and only recently began issuing mobile-money banking licenses.

There and in other countries, OPay and Opera could face regulatory pitfalls around data-privacy and national security concerns related to their Chinese ownership (see Huawei’s saga in the U.S.). Nigerian regulators demonstrated they are no pushovers with foreign entities, when they slapped a $3.9 billion fine on MTN over a regulatory breach in 2015 and threatened to eject the South African mobile-operator from the country.

An equally important lesson both startups can glean from M-Pesa is the imperative of shaping product and outreach to connect with local demographics, starting with product-market fit.

OPay and PalmPay enter a mobile money landscape that is much more competitive across Africa with ambitions to operate in multiple countries.

Like M-Pesa, they need to be nearly perfect in aligning their products to local consumers preferences and needs — from functionality, to branding, price points, agent network, and marketing.

If they don’t get that right, all the VC in the world won’t get Africans to use their apps. And consumers from Nigeria to Ghana will opt for payment products of lesser funded fintech startups who do.