Welcome to this transcribed edition of The Operators. TechCrunch is beginning to publish podcasts from industry experts, with transcriptions available for Extra Crunch members so you can read the conversation wherever you are.

The Operators highlights the experts building the products and companies that drive the tech industry. Speaking from experience at companies like Google, Brex, Slack, Docsend, Facebook, Edmodo, WeWork, Mint, etc., these experts share insider tips on how to break into fields like product management and enterprise sales. They also share best practices for entrepreneurs to hire and manage experts in fields outside their own.

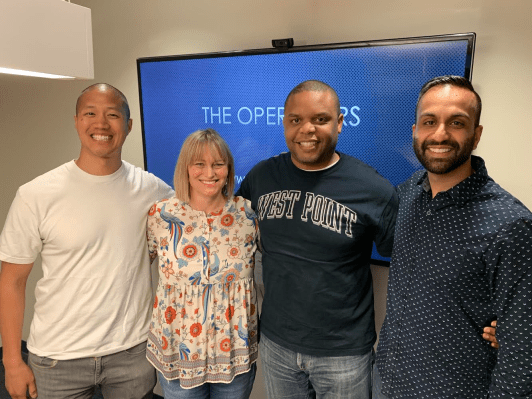

This week’s edition features Lorilyn McCue, product manager at Slack, the fastest growing enterprise software company ever that recently skipped its IPO to do a direct listing (like Spotify), and Jamal Eason, a senior product manager at Google, a company recognized as a training ground for the best product managers. Lorilyn and Jamal share their experiences and explain what product management is and isn’t, how to get good at it, and how entrepreneurs should think about product management as a discipline.

Lorilyn and Jamal are also both West Point graduates and military veterans who have deployed overseas. They are experienced operators in not just Silicon Valley but also from their days serving in uniform.

Neil Devani and Tim Hsia created The Operators after seeing and hearing too many heady, philosophical podcasts about the future of the world and the tech industry, and not enough attention on the practical day-to-day work that makes it all happen.

Tim is the CEO & Founder of Media Mobilize, a media company and ad network, and a Venture Partner at Digital Garage. Tim is an early-stage investor in Workflow (acquired by Apple), Lime, FabFitFun, Oh My Green, Morning Brew, Girls Night In, The Hustle, Bright Cellars, and others. Neil is an early-stage investor based in San Francisco with a focus on companies solving serious problems, including Andela, Clearbit, Recursion Pharmaceuticals, Vicarious Surgical, and Kudi.

If you’re interested in becoming a product manager, furthering your career in that field, or starting a company and don’t know when to hire your first PM, you can’t miss this episode.

The show:

The Operators, hosted by Neil Devani and Tim Hsia, highlights the experts building the products and companies that drive the tech industry. Speaking from experience at companies like Google, Brex, Slack, Docsend, Facebook, Edmodo, WeWork, Mint, etc., these experts share insider tips on how to break into fields like product management and enterprise sales. They also share best practices for entrepreneurs to hire and manage experts in fields outside their own.

In this episode:

In Episode 2, we’re talking about product management. Neil interviews Lorilyn McCue, PM at Slack, and Jamal Eason, a senior PM at Google.

Neil Devani: Hi and welcome to the second episode of The Operators where we learn about people building the companies of tomorrow. We publish every other Monday and you can find this online at operators.co.

I’m your host Neil Devani and we’re coming to you today from Digital Garage here in sunny San Francisco. Today’s episode is sponsored by Four Sigmatic. Four Sigmatic’s Lion’s Mane Mushroom Coffee has all the coffee’s focusing bark with none of the jittery bite. Lion’s Mane promotes productivity, focus, and creativity all while being a healthy alternative to that daily cup of coffee. Go to foursigmatic.com/operators-special to try out Four Sigmatic.

Joining me today we have Jamal Eason, a senior product manager at Google. Google is one of the top companies in the world when it comes to product management.

Also joining us is Lorilyn McCue, a product manager at Slack. Slack is one of the fastest growing enterprise software companies ever and just recently filed for its IPO. Lorilyn and Jamal, thank you for joining us. It’s a pleasure to have you both.

Just to start, it would be great if you could give us a little bit of your background, where you’re from, where you went to school, and how you got into becoming a PM.

Lorilyn McCue: Sure. I’m from Orlando, Florida originally. This story will sound very similar in a little bit because Jamal and I have similar backgrounds.

I went to West Point, the United States Military Academy for undergrad. I studied computer science there. I served for 10 years in the Army. I flew Apache helicopters for six years and I taught back at West Point for three years.

After that I really had no idea what to do. Jamal was actually helpful in that process. In that I said, “I was thinking about going to school using the GI Bill.” I was considering business school, and he helped me narrow it down to some schools that made sense.

I ended up going to Stanford’s Graduate School of Business on the West Coast. I guess a fun fact about that decision is I was thinking East Coast versus West Coast schools. And when he mentioned Stanford I said no, because there’s a lot of traffic California. And he said, “No, don’t worry, you can bike around campus.”

This was a very convincing explanation for me. That is why I am here today, is because Jamal knows me well enough to say, “No Lorilyn, you can bike.” (To Jamal) I did bike around campus by the way. It was great. Thank you.

And then I did an internship at Google in product management. The summer between my first and second year I really loved product management. I wanted to be at a little bit smaller of a company so I ended up going to Slack.

I’ve been there for about two and a half years now. I started off as a product manager on the new user experience team and recently changed to platform.

Devani: Awesome, great!

Jamal Eason: Myself, I grew up in Los Angeles, California.

Devani: The land of traffic.

Eason: Yea, the land of traffic.

McCue: You probably didn’t bike there though.

Eason: No biking. Similar story, I also went to West Point for undergrad and studied computer science. Lorilyn and I shared multiple classes together there at West Point.

But instead I actually went to the Signal Corps, basically the branch of the military that does satellites and data communications.

I spent the last five years actually in the Army doing that. So, data centers, satellite communications, I was stationed over in Germany, I did a tour in Iraq. And then I was thinking what’s the next step for me. I chose business school from that.

I had a few different mentors and friends who did business school and I decided that was the pathway. I applied to a variety of schools, I knew that at the onset I wanted to be in technology, and I knew that business school is a way to do that.

I ended up going to HBS after applying to a number of schools. There, I kind of got exposed to a number of different fields and industries and found that technology is definitely the spot that I want to go into.

In my MBA internship at Intel, doing product strategy, I realized that I really want to get as close as possible to the product, and that was that exposure.

After graduation I actually joined Intel for the Rotational MBA Program, doing everything from product management, product marketing, some venture capital investing.

And that exposure I kind of realized, yes, product management is definitely the thing I wanted to do.

If anything else when I left business school I didn’t know what that was. I actually joined a startup when I was in business school helping to work on a mobile app. I was just doing everything for a startup. I didn’t have a title. I didn’t know what that entailed.

When I came to recruiting they asked me, “Hey, do you want to do product management?” I was like, “What does that exactly mean? Explain the description to me.” I was like, “I’ve actually done that in this capacity, both at Intel and a startup. And it was actually a good fit.” I knew three years after graduation that was the role I wanted to do.

Where I am now, I’ve been at Google for the last five years as a product manager on the Android team. Specifically, my product is Android Studio, helping developers make apps for Android.

My users are the small studios, to large enterprises, to full-time app companies who use Android Studio to make apps for the Android platform.

Devani: I love that you guys have that experience together. You’ve gone to school together. And then you pulled her into the world of being a product manager. Just to start, for some of our listeners and our audience members who aren’t as familiar, what exactly is product management? How do you define it?

McCue: I think Jamal should answer since he convinced me to be one. So obviously his answer is very clear and compelling.

Devani: Let’s throw it to Jamal.

Eason: Sure. I think the key thing is you’re basically the voice of the user into the company. I think in that respect product management is actually not a new thing. And at least in my research, it’s been around in the world for a while but I think in tech it’s kind of a new intersection of both business and technology.

That’s interesting because we have a lot of smart engineers working in great products but sometimes they’re lacking the insights of the user, and a lot of business people who want to drive the business but don’t have a lot of insights.

This intersection of both business and technical capacity is there, and really the role is, how do you understand where the products can be used, and what the priority should look like. And you’re really focusing on, how do we prioritize the right things to the users so that the design team and other teams together can make that an actual deliverable product for users to use.

McCue: A lot of times when I think about it, I just imagine a room full of engineers and gradually there’s more and more engineers. And there’s some other people doing sales function and marketing function.

Eventually, some people are just naturally drawn to like, “We got to coordinate with sales on this. We got to figure out what the customer wants. We got to coordinate with this guy, coordinate with this person.”

Eventually, there’s one person that’s drawn to that. And they’re also drawn to the idea of what do we build next, like what’s the biggest high priority item that we should do?

Let’s imagine this person was like, “I’m going to stop engineering quite as much and I’m going start doing these coordinating efforts, figuring out a roadmap for what we’re going to work on.” And then I just imagine that’s how a product manager evolved over time. I’m not sure if that is what happened. That’s what I imagine.

And then this person is like, it turns out I like all those coordinating and planning more than the engineering. I understand the engineering enough… that’s the visual I have in my head.

Devani: I’m a visual learner, so thank you. What do you think is in the scope of being a product manager and what’s out of the scope of being a product manager?

Eason: When I first joined a team at Google we had engineers and no one else supporting us. I find that product management includes everything and nothing, depending upon the scope and maturity of the products, right?

At one point there’s a bit about getting requirements and understand the users. But then at some point we need to understand the design. We need to design some features. A visual designer, sometimes you’re doing some design stuff.

There’s an aspect of running the project, making sure things have a deadline. There’s a project management component to it.

Sometimes, you’re like, “Hey, I now need to start marketing our ideas.” There’s a product marketing component to those things.

And as your product evolves, those are actually different responsibilities that, at the core of it, you’re coordinating with that stuff, but sometimes you have to do those types of things.

I think the scope, as I said, kind of varies based on the product. And I wouldn’t be too confined, like “I only do this one set of things,” because sometimes you need to kind of step out that realm and do these other tasks.

Basically, I see myself doing everything except coding and engineering because I think if I’m doing that, I’m probably not spending my time in the best capacity. But everything else I want to make sure that the engineers are focused on getting their product actually built, and I can help do everything else outside of that to make sure they can deliver a product.

McCue: One thing I love about the job is that you definitely have a lot of different hats that you wear. One day you’re more of a data analyst, and you’re coordinating with your analytics team figuring out what’s really happening with this data.

Another day you’re talking to legal, figuring out what’s the best course of action for a given thing. Another day you’re coordinating with your engineers and discussing a different technical trade-off.

Sometimes you’re talking to marketing. It’s like you’re using a different language. Like whatever function that you’re talking with. There’s really nothing that’s off-limits, but I think it’d be a bad day if we were coding.

Although the one time we were talking in Slack, and one of the PM’s said, “I’m going to try coding this.” We have this emoji which is a little popcorn emoji to be like, “I can’t want to see how this goes.” And someone reacts to it, it was like popcorn and I was like, “Popcorn…”

Eason: The funny thing was that, at some point we needed to do some metrics. I was like, I want to learn Python and do it myself. And then no one wanted to do this project.

I spent a weekend learning Python and put together a little model. And then I presented it the next week, and they were like, “We can do it better.” I was like, “Here you go.”

Sometimes it’s dabbling into something that can motivate people. We shouldn’t be afraid of coding. I’m just not doing it full-time.

Devani: It’s interesting because you both have that computer science background, right? What was it about your experience that led you to ask Lorilyn, “Hey, you should be a product manager.”

Eason: It’s kind of actually related to the more broader concept of how people transition from different careers. And specifically for us, it’s about transitioning from the military to tech and product management.

One thing actually our product management is like unless you’re in a certain circle or certain vein you don’t even know that it exists. I think one thing that was helpful is that I left the military five years before she did, so I’d been through the business realm, I’d been through companies and seen what worked or did not work.

And I think a lot of times, it’s interesting, there’s actually a parallel I between the military and tech. In the Army we actually have this role that’s called a platoon leader where you’re basically working with a number of soldiers to actually execute a mission. But it’s your role as a leader to define the strategies and the priorities and what needs to happen. And this is a very fundamental role that all officers do in the army.

So, ironically, as a product manager, you have a very similar capacity, where you’re defining strategy and direction, and you work with great engineers to actually execute on this. And so when Lorilyn said, “Hey, I want to find this role that has a match in the military,” I was like, “Well, there’s actually something that’s very similar to this… product management!” I explained it in those terms to her and it made sense.

I think for other people, even outside the military, it’s really understanding what are you currently doing, can be framed in product management, and sometimes there’s a match there. And I think that worked well for us.

McCue: In the past, have really looked for a computer science degree in product managers. I think currently that’s starting to loosen a little bit. And that depends a lot on the company. But a lot of times they have some technical experience. And if they see a CS degree, it’s like a thumbs up, they would be qualified as a product manager.

I think that’s kind of funny because I hadn’t coded since school, other than maybe something like flight planning software, which doesn’t really count. I felt silly.

At least it did indicate I understood technology. For me, I really thought about three circles. I had this technical background, a love of technology. I had leadership from the military. And then I had the business school stuff that I was learning. I felt like product management, the way Jamal described it, it really fit in the middle of those things that I was interested in and had skills in.

Devani: If we’re talking to someone that’s coming from a different background, let’s say they’re not a computer science grad, what would your advice be on how do they work themselves in the position where they could be eligible for a product management role, assuming they’re looking at a company that doesn’t require that they had a CS undergrad?

Eason: I think the great thing is that now in 2019, learning technology and programming is just a few clicks away. Having a basic understanding of technology, I think, is a prerequisite for the role.

It doesn’t mean, to me, like I need to have a computer science degree, but do you understand what a database is or, what’s cloud computing, understanding these concepts. So when you’re making these decisions as product manager you have that baseline.

I think I mentioned this to a few folks, there’s lots of things you can take. There’s boot camps and online courses you can take. Showing that initiative like, “I may not have a technical background, but I’ve done these additional things” really shows that you can take the effort.

Because ultimately what happens is in the job there’s some new technology, some decision, that’s going to require you do some research. And it’s usually some technical research. And if you’re showing that you have the capacity and interest in doing that stuff, I think that shows employers that although, 10 years ago, you didn’t take computer science, but it looks like today, this is your interest area. You can supplement that with your extra work you do outside of work.

McCue: For people who are transitioning it’s often easier to get a job at a company in the role that you have a background in, and then transition into product management. I can think of maybe three or four PMs at Slack that’ve done that.

At least at Slack, with the size of the company that we’re at, it’s easier to transition into it after you’re in the company than transition into it.

Right now we’re looking mainly for product managers that have done the exact experience that we’re looking for already in a different company.

Eason: That’s true. If you look at the size of companies that also buries the bar of what they’re looking for. You’re right, at Google there’s a plethora of different jobs, from marketing to HR. And I think from every different discipline someone has made a pathway to product management. And I think that’s definitely encouraged.

The bar is definitely still there. You still have to do all the same interviews, but it’s easier to have someone being an advocate internally saying, “This person’s done great. He understands the product.” They can build a network and get interviewing prep that’s there.

I think as you go to smaller companies, they may be a little bit less accommodating, because if it’s only five people in a startup, we don’t have time to train you. You need to learn that stuff.

Somewhere in that range of companies. Lorilyn, she said she went to Google but she wanted to do something smaller, and you have to base it on your fit. That might be a fit conversation. What’s going to actually provide me the coaching mentorship for product management? Is it a direct hire for product management, or is it a two-step process?

You can ask those questions if people have already done it, that’s a great thing. And if they’re supportive of it that’s also great. Because not everyone has to apply directly to product management. I think a lot of people have done a transition to get there.

Devani: Yea, that makes sense. I want to be a product manager. I’ve just been hired, maybe as an assistant product manager or an entry-level role at a startup in product management. How do I become the best product manager I can be? What’s the roadmap for that?

Eason: Honestly I’m always a student. As I mentioned to you earlier, I didn’t have a clear definition of product management early on my career, and I don’t know folks when they were in undergrad like, “I want to be a product manager.”

I actually continuously read books. I look at blogs and see things that are going on just to kind of get a sense of what people are defining as product management. And I do a healthy amount of YouTube searching, like what are people saying about product management, what they’re doing and not doing? There’s a lot of external research I’ve been doing.

And I think a company like Google or more mature companies is, you also see other mentors and other people doing product management, see how they’re doing.

Obviously, they got it right. They’re promoted, they’re doing something well. And sometimes it requires having a lunch conversation or in a coffee shop, things like, “Hey, how did you think about this?” It might have been happenstance, or some are very logical, and I just got to ask those questions.

I think a bit of personal research, just always be hungry for it, because I think it’s always evolving. But then also it’s asking people and gaining that insight. Lorilyn, what’re your thoughts?

McCue: I thought it was really helpful whenever I followed my own curiosity. There’s two voices inside of your head whenever you see something that you’re not quite sure about. It’s like, on one hand I could pretend that I kind of know what’s going on and just blow past it. Or you could honor that curiosity and say, “Can we just slow down? I don’t quite understand what’s going on here.”

Every time that I dug into stuff a little bit more, whether it was an engineering question, or it’s a user problem that I didn’t quite understand, or a query where I was like, “I think maybe if I figure this out I can do more of this stuff on my own.” Any time I dug into that it was really helpful.

That’s one thing. Especially in the beginning, you can just be a sponge of curiosity, kind of like that learning thing that Jamal said.

The other thing that was helpful is getting coffee with a bunch of people throughout the company in different organizations, like have your friend in sales, have your friend in customer success, have your friend in legal. Have somebody in each of these groups that you can ask the questions, like, “What’s going on here.” And they can translate for you.

You build that relationship, and you just get a bigger view of the company in general and how everything fits together. It’s almost always an invaluable understanding that you gain through forming those relationships early on.

Devani: It seems there is a lot of relationship building where you’re not necessarily authorized as a manager to tell people how to spend their time or what to work on, but you have to convince them and persuade them to go on a certain path. Do you guys find that to be true? How do you manage that if so?

McCue: Definitely. It’s funny, everybody always says, “It must be really different in the military where you’re in charge and everybody follows your every order.” It’s not totally like that. In the military, they teach that leadership is all about forming relationships and being at the front, and having your people want to follow you, and providing a compelling mission and reason to do what you’re doing. It’s not telling everybody and that’s how it works. It would be a horrible experience if it was like that.

And I feel like product management is similar. The engineers that I’m working with are not my direct reports at all. But we’re forming these relationships, and we are working together to create this mission. And I’m trying to convey that vision and say why we’re doing things in a way that’s motivating. And communicating that to other people in the organization. It’s imperative that you have that skill.

I love that. I really enjoy forming relationships. I think it’s a great part of the job. It’s like a perk for me.

Devani: You get paid to build relationships?

McCue: Yeah. I meet really cool people and talk with them and try to do cool stuff together.

Eason: I agree.

Devani: Let’s talk a little bit more about product management in terms of it being a role that someone needs to hire for. We’ve talked about if you want to go into product management, but let’s say you’re starting a company and you’ve been a full stack developer, or you’ve been on the sales or BD side. And now you have to manage product. You’ve never done it before.

What advice would you have for someone who knows they’re not going to be a product manager, but in the interim they have to basically play that role?

Eason: I heard two parts, like how do I hire someone and be the product manager in the company?

Devani: Yeah, let’s start with B and then we’ll move to A after that. I just started my company. I have no idea how to manage a product but I know I have to do it.

Eason: I think it’s a realization that it’s… I was doing venture capital for a little bit and you always run into a lot of great engineers with a lot of great engineering ideas but they’re not understanding how people would actually use the product or buy the product or have the user experience.

I think realizing that at some point someone has to use your service or product. You have to take that mental assessment. Can you objectively get away from your product and say this product is not going to work.

Sometimes it’s hard for you to say, you spent three months working on this product and realizing it’s not going to work. And so if you don’t have that product personally you have to be very conscious about it. Although there’s a lot of engineering work that’s going on here, or I may have a great customer that’s using this, there’s always that end-user experience that needs to be kept in mind.

I think that kind of relates to how you would hire someone. If you realize this is not a skill you have and sometimes it’s hard to do, find that person who can be objective. And find a person who’s going to be that voice of reason where it’s like this is super cool. It looks awesome, but no one’s going to use this.

And having that realization first, before going out and rolling your product out and realizing in day 1 no one’s using it, you could’ve figured it out internally. I think hiring someone who can do that for you, if that’s a gap for you, I think that’s one assessment.

And the other part is it kind of relates to Lorilyn’s part is that you try to find someone who’s actually a bridge builder. Essentially many times you might have a great engineering team or a great sales team, but they may not be talking to each other.

Someone who’s not well-versed in understanding or trying to understand what’s the sales ramification of this decision, and the engineering ramification of the decision, the marketing aspect of the decision. Because it’s not usually the black and white decisions. It’s some sort of multitude of things had to go on and understanding how this prioritizes and impacts the product.

I guess in hiring someone, what are the gaps that need to be bridged between? You might need a brighter person who understands UX and engineering, a person who has marketing engineering skills. And optimize around those gaps you have so you can have that growth in your company.

McCue: I would say with the B thing first, if like you are the de facto product manager, like, “Congrats, welcome, you’re the product manager.” I would say you can’t spend too much time talking to users and creating systems that enable you to put an early version in front of a user as soon as possible.

Whether you’re using a website like usertesting.com, or you can just throw a prototype in front of people and get their actual thoughts on it, or whether it’s having a set of beta customers who will be forgiving and give you really honest feedback. Or even just taking a picture of something, or you know some guy a couple blocks down who uses your product, going over there and being like “Would this work for your needs?”

I can’t count the number of times that I thought we understood the problem truly and thoroughly, and then when we show an early prototype we would realize we do not understand this problem thoroughly.

One example we had is we have at Slack there’s this grid product. It’s like our premium product where you can have different Slack workspaces, teams inside of your company so sales could have their own Slack workspace, and marketing can have their own Slack workspace. But those people could still talk to each other and see what’s going on.

And so I’m on the platform team and we thought, “If Acme, Corp. wants to decide whether to install the Google Drive app they’re going to either have a company-wide policy of either we allow the Google Drive app or we don’t allow the Google Drive app.

And we recently had a developer board where we chatted with customers. And a person at a company like this said, “Oh no. Each division has their own agreement with the different software providers. This app could be good on this workspace with sales but not good on legal.”

And so we realized that instead of having apps approved at the big company level they really had to be pushed down to the workspace level, which kind of changed the way we thought about how our approval process and flow should go. But that’s just not something I would’ve known without talking to that person and without them seeing a picture of how this could go.

I think if you’re a product manager, like just try to get things in front of users as soon as possible and as rough a form as possible before you start coding, before you make one-way doors that you can’t come back out of.

Eason: I would have to add this. Lorilyn’s talking about doing fast-forward types and MVPs. You may not know that. I guess you just think, that’s a cool thing, and the whole process of what’s formally called the product development life cycle may not be second nature to you.

Formerly in my life, I used to do teaching and I used to teach product managers. And lots of people who actually take the course are CEO’s who are like, “I want to be good at product skills. I just want to take a course on this.”

Again, back to my self-learning, there are things you can just be like, I want to learn about product management. Although I’m not wanting to be one, I can just learn about some skills. And I’m understanding AB testing, prototyping, user research things, these topics that are more probably product manager types of things they kind of run. But just being familiar, if you’re doing it or not doing, it can help you be more informed about if you’re doing the right thing for your product or not.

Devani: Before going into the hiring and managing aspect of it, can you give me some differences and contrast between a PM when it means product manager, versus a PM when it means project manager, versus when it means anything else, product marketing, whatever else you got.

Eason: I’ll just talk about my personal experience. When I said I joined my team, I didn’t have any support to like, “Hey, here’s this product.” And I look around Google and was like, “There’s this other person doing this thing over there. Can we get one of those?” They’re like, “No.”

Devani: You’re on your own.

Eason: Eventually over time, we actually hired for each of the positions that you described, and I definitely know the time when I was doing it and when I was not doing it.

For instance, one thing that’s kind of confusing for some people when they’re hiring is like product manager versus program manager. Program managers, they’re primarily responsible for driving the schedule, and the release, and bugs, and sort of the whole process of things. And the distinction is they’re not typically a person who’s defining the requirements and setting what we’re going. But they’re an integral part of the team in getting all this process done.

Sometimes, as I mentioned earlier, as a product manager you’re doing some program manager things, but that can actually hurt you. If you spend your time doing all these process things and never gone around to doing user things, you’re kind of hindering the team.

The third part of management is product marketing. Really it’s like who’s in charge of doing the go to market plan. It can be from the social media or your website. Maybe if you have a bigger team, like press relations, or other things of that nature. Who’s crafting all the things we’re doing around getting this product out. And if it’s a virtual product, it’s software-based. But if there’s any retail components like, how do you talk to retail partners, or anything else of that nature.

When I didn’t have that person, I spent a lot of time doing slide decks and doing graphics myself, and doing these other attributes. I actually enjoyed it. It was actually quite fun, but again, this takes time. This takes time away from these other roles.

And so really we’re having one or two people who were focused on like, “The product is almost ready to go. How do we get people to start using it? What sort of ad or ad campaign process or co-promotion process?”

All these things I’m familiar with from my MBA perspective, so I think that helps. I know what’s supposed to happen, but…

Devani: You know you’re not supposed to do it.

Eason: I’m not supposed to be doing that stuff. It was very helpful when we hired them, like now I can do these other roles here.

McCue: We have program managers at Slack. I recently chatted with them to get an explanation of what project management is versus program management. Like Jamal said, the project manager is going to take Project XYZ and make sure there are processes to make sure it’s on time.

The product manager will decide exactly what the user problems are that we’re tackling with this project to create a spec as to what exactly we’re going to do, and decide what order we’re going to do these projects in. And then the project manager is like, we’ll help them make that happen on time.

We don’t have project managers at Slack, but you can think of a program manager, at least at Slack, the way we call it is somebody who will look at many projects at a more strategic level of projects.

For example, I worked with a program manager when we changed our terms of service, which impacted a lot of different groups throughout Slack and required a lot of coordination. We have a program manager that thinks about our conferences that we have. It’s not just one conference. It’s like many conferences throughout the world.

We have those program managers. And I think all product managers would love to have a project manager because…

Eason: It’s awesome.

McCue: I’m very jealous. And then the product marketing manager, they are more focused on helping make the features but also the go-to-market plan. “We’ve made this feature, now how are we going to launch it? How are we going to promote it? How are we going to get people to know about it? How are we going to coordinate with other people in the company to make sure we’re cross-promoting stuff?” That’s something that’s helpful to have as a partner as well.

Devani: This is the perfect context. That was the lead in for the next question here which is, we have this scenario where you have a small founding team. Maybe you have a couple of people who can do development. You have a couple of people who are more customer facing in doing sales.

They’re going to hire their first PM. Everyone agrees, we’re going to hire a PM. Of all these different things that PM’s do when you don’t actually have a separate project manager, product marketer, program manager what do you think is the most important thing for the first PM to really take on? Maybe it’s all those things. I don’t know.

Eason: In my observation, usually if a founding CEO or a founding engineer who founded the company, it’s actually taking away the product from that CEO. The CEO can focus on being the CEO, and not being chief product manager at the same time.

Whatever their product is, that’s usually what’s going to be scoped. What’s preventing us from getting from our current state to actually getting them to users? Especially it’s product number one. It’s more than just the software. It’s like a personal release of your baby.

Devani: Yeah, it’s the emotional, psychological aspect.

Eason: “I created that.” “I know. But now you have to be responsible for this thing.”

And I think the other part is kind of to Lorilyn’s earlier point, it’s like many times it’s kind of breaking down, here’s this great, amazing product. We need to get those out in front of users as soon as possible. So it’s usually like that first MVP, like how do you get someone with the first set of users.

For instance, when I was working at my first startup, we were developing this out for a few months. And then we’re like, “This is going to work.” And then we’re sort of like managing around for a little bit. I was like, “We should get some people.” And then sometimes I have to say that question like, “Let’s get some people who actually use this thing.” You’re like, “Yeah, that makes sense.”

Because at some point if it’s a startup you’re going to keep it secret. No one’s going to know about it. But at some point if you want some people to use, then it’s no longer a secret, you got to make a public announcement about it, or at least have some sort of trial so we can assess it.

I think it’s one of those two things. Like, taking away from the initial CEO, and then really driving towards that initial MVP. Especially if no users are using it, it’s an important feedback to have.

McCue: Yeah, I’d agree with that. I think the combination of the strategic focus as well as being able to parse that strategic focus into a set of manageable little mini things where there’s a lot of check in with users along the way, I think that’s the most important skill the project manager can have.

People are going to inherently make that happen, just because it’s so painful to be in a poorly executed project to where systems will try to evolve somehow. And they may be the best ones. And then the market you have to think about it too, but you can’t market something if you haven’t built the right thing.

Eason: The biggest trap is always, don’t get stuck in doing those other roles in continuum. Because essentially what ends up happening is that, let’s say you over-index on product marketing stuff, and eventually realize, we might need another product manager because it doesn’t seem like it’s getting done. And then I’m like, I’m the product manager. But no, there’s still other work that hasn’t been done.

I’ve seen it time and time again, so make sure you’re very clear with everyone. This is what I’m doing. This is what I’m not doing. And so everyone’s on the same page.

If they’ve never had a product manager before, that might require having a lot of one on one conversations saying, “This is what I’ve done, or this is what I need to do.” And setting the stakes.

Sometimes the title can be very ambiguous, going back to your first question, not everyone knows what they’re supposed to do, and they may just give you some random things that may not actually help you in a career as a product manager but also help the company and the product. Because you’re spending your time working on stuff that’s not value added from the product perspective.

Devani: I think there’s this confusion around how wide or narrow the scope can be. And there’s also examples where you don’t have a product manager, but you can still get a product out the door because someone is the de facto serving as that, whether it’s a founder or an executive role, or if it’s someone who’s an engineer who’s doing all of that work, or if it’s a designer whose job is understood to be just designing, but they’re actually doing product management on top of it. And that kind of abstracts the fact that you’re missing that role, because someone’s just picking up the Slack. No pun intended.

Moving forward, I would love to hear from you guys, just some stories of times where you had some big wins and/or big losses as a PM. Or something fell to you. You had to make a decision or you had to drive direction. Can you share some stories?

Eason: I can share my earlier days with Google. My product is basically to enable lots of things on Android, lots of products. Android is on phones, TVs, automobiles, and wearable devices. And so I have this grand vision that we need to help developers in all these platforms.

What ends up happening is that inevitably, in my space, is that there’s a need for consumers to buy these devices. There’s also a need for the app developers to make apps that run on these devices.

So there’s always an index, so let’s get the product out the door. Whenever a user buys a smartphone, the first thing you want to get is the apps. If the apps are not there, the product is not that helpful.

I feel like in my case, when I first joined the team I was like, “We’re getting the developer story, why do developers matter?” It took a while for me to convince everyone that this is an important factor. It’s like one of my initial lessons. All that great strategy actually required selling this to lots of people and having some patience.

Ironically six months to a year later, “We don’t have that developer.” So I can pull up my PRD from a year ago. Here is the plan. I don’t want to say I told you so. Let me just send you this email.

But I think it’s good to have vision, but I understand that it may take a while to sell that vision, especially in this case, I was working with four or five major product teams that were focused on one major thing. That was difficult.

Success. One thing that’s really cool for me is that when you launch a product, people actually want to use and are excited about it. I think in the developer space, in contrast to consumer products, when you launch a consumer product, there’s this, nebulous consumer, you don’t know who that person is. You’re like, you’re using my product but you don’t have a name to face this.

In our product it’s like, developers are pretty passionate about things we’re using. And they’re pretty big on social media, Twitter, Reddit, or whatever, and they go to these conferences.

The first time we launched a feature that basically helped productivity of developers, like to do some pain point. And then within 30 minutes of launching that feature, they’re like, “This is amazing.” You get this instant feedback.

I can remember that first social media confirmation. These people actually download this thing and actually use it. It’s pretty powerful.

And in the same regards to having a pain point is that when we launched our product we weren’t quite there on quality or an issue it was kind of buggy. Within 30 minutes they’re like, “This sucks.” You can feel that pain.

It’s the highs and lows of having direct user feedback and knowing if we’re doing the right thing or not.

Devani: People rely on your product to do their job, right?

Eason: Exactly. It’s a pretty important thing.

McCue: Actually I was thinking about… I’m going to say something that sounds like it’s going against my own advice. I remember we were building a feature on mobile when I was on the new user experience team. And we were addressing a couple of problems. Mobile was a little bit more confusing, and instead of signing into a team, some people were creating a completely new team not realizing they were doing that.

Also some people had many, many teams that they were a part of on Slack and there was a real pain to remember… What was the website URL? What email did I use? What password do they use?

And so we’re developing a new way to sign in where you put it in your email. You get an email. You click on the button and then we boom sign you into all of the teams that you’re associated with. It’s very helpful for some people in this room.

And so we really were focusing on those two particular use cases the most. And we realized at some point that some companies have really fancy ways of signing in. And those fancy ways of signing in made this solution a little more complicated.

We wanted to get a product out the door and be able to learn and reiterate from that. We basically scoped down the project, and in doing so we made it a little bit hard for those who had these special ways of signing in. These people are often the ones that are the biggest companies that are paying the most.

I think what I wish we had done in that case is waited a little bit longer to make sure that we had really addressed those really important users as well and released a little bit later. Because the V1, trying to make it go out faster-made things actually a little bit worse for these people who are signing in this special way.

And so for me, the lesson was always try to get to the most minimum viable product, but also consider the impact on the people who are really driving your business. And they may be considered edge cases, but often they’re really important. That was a good lesson for me.

Devani: You gotta be really comprehensive and think through every possible eventuality.

McCue: Yeah, which is tough.

Devani: It’s a good skill to have. Can you walk us through, I would say a typical day but I’m sure day-to-day is very different. So how about a typical week, what are the different conversations you’re having, the different work you’re doing that’s just solo work? How do you manage your time and things like that?

McCue: One thing that’s interesting for me is often at times I’m at different phases of projects, I’m managing many projects at a time. In the beginning, I’ll be figuring out the user problem, making a brief that captures the true problem that we’re addressing. I’ll be getting data to back up that this is actually a problem and how best to address the most people in the best way.

I’ll be talking with engineers and designers about how to address this the best way. And then in the next phase, where we’ve defined the problem and now we’re really speccing out what our solution could look like, talking with designers, bringing in engineers for feedback. And then we kind of figure out what we’re going to build and then we’re building it. We’re measuring it and making some kind of decision, because I do a lot of experiments.

The last important part is telling a story, saying, “Here’s what we learned.” Make sure the company understands that, and telling what the next steps are. But the thing is I could be at a different phase of this for each project. This week I’m in the story-telling phase of one project. I’m saying, “This is how this did.” For another project I’m in the ideation stage, trying to figure out what we’re going to do, what problems are we addressing.

And then on another project, I’m kicking off. Like we’re in the kick-off phase. I had a kick-off this week. I’m trying to figure out how to best capture this. During the week there’s a lot of different tasks switching that’s going on, what phase we’re in.

There’s also the next quarter planning, like planning for the year, which also takes a lot of bandwidth and figuring out. We use OKR’s which is objectives and key results. We have a set of goals for that quarter and measuring those.

This week I’m in different phases of this project, which sometimes incorporates a lot of meetings. There’s a lot of meetings. If you don’t like being in meetings, just don’t be a product manager.

I think I asked you this at some point as like when do you do your work. And you’re like, “I do my work in meetings. The meeting is my work.” I was like, okay. It’s true. You make decisions and you really are planning things in those meetings.

I like to work from home on Thursdays, which gives me a little bit of space to do more strategic thinking, what’s happening next, what are we doing next? Take a step back. That’s been helpful for me.

Eason: I agree with her. There’s always these projects in flight. But I like to think about it also as another imagery. If you think about a tornado, it’s like the spinning chaos around. But in the middle, there’s this zen. That zen for me is usually the morning time. I come in pretty early just to have that initial zen when no engineers are there, no one’s in the office, and I could be working on next requirements or responding to emails.

Come 9 o’clock through 4 o’clock, it’s pretty much meetings and organizing and briefing. That is kind of the deal for product management. I remember one of my engineers, they tried to add a calendar invite and were like, “Hey, your calendar is so full.” I was like, “That’s kind of what I do.”

That same engineer, I think they literally have two meetings in a week. And the rest of the time is coding. “I can’t meet because I’m coding.” I was like I can’t just block off my entire week not doing any of that stuff.

I think it just comes with it. I think it’s what I mentioned, this is continuous projects and always in flight. All the phases that she described are spot on. But I think one key thing is how do you find your time to do this zen work, you can do taking the Thursday off, or working from home, or coming in early. Because ultimately all these different tasks can consume you.

Comparing it when I first started at Google, it was like my peak of creating a stock of information. I was pumping on that every week, it has ideas, putting it down on paper. As you start getting these things in flight you don’t have much time to create as much.

It’s definitely a challenge in my mind, how do I keep that same momentum of idea creation in that space.

Devani: In addition to content switching there’s a lot of parallels, a lot of competing interest and just managing multiple projects into one as opposed to, maybe if you’re an engineer and you have one problem that you need to solve, and you’re going to solve that problem before you move on to the next one.

Eason: And there’s nothing wrong, either way, either approach, just going in…

Devani: If you don’t like you’re probably not going to like this job.

Eason: Yeah.

McCue: Something that I’ve done, I know some people have a more consistent work schedule. I know Jamal is more consistent.

Eason: I try.

McCue: I’m a little bit less predictable in terms of when I know I’m doing my best work. There are some times where I’m just really in the groove. I always text my husband and be like, “Hey, do you mind if I surge tonight?” Because I’m just in it, so I’m really productive in that moment, so I’ll just stay a little bit later that night.

And then there’s other days where my brain is fried at 4:30 and I could try to stay longer but there’s really no use. I should leave now.

And so I’ve been a little flexible in my schedule and allowed myself to surge when I’m really productive and just pull back. And I think it all evens out. I think a lot of people like working that way or should work in that way.

And a lot of times the things that I do when I’m surging they really pay dividends in the months to come. Like that one doc that I finally wrote up saying, this is how we’re thinking about this problem. I reference that a bunch of times. Whereas if I just try to do a little bit of that each day, it wouldn’t have happened.

Devani: Yeah, it may not be as efficient. You’re kind of maximizing on your own awareness of when you’re productive and when you’re not.

You both have managers, I’m sure. What makes a good manager for managing a PM? And maybe what makes a bad manager? …I don’t want to get you guys in trouble.

Eason: I think it comes with different things. I was going to compare this to actually… In the Army it’s a little bit more defined. Like here’s your role and responsibility. People have some complaints about that, but I just have that clear responsibility. Here this is your responsibility, this is your task, and you derive your own process.

I think managers who can set that up where it’s like, “Here’s your resources. Here’s the general area just kind of figured out”, I think that’s where product managers can thrive because you’re supposed to kind of like understand these hairier problems.

I think in contrast, where, if a manager is like on the proverbial micromanaging, and here’s what you need to be doing, this is not a job that works well with that. If you feel like you’re being micromanaged it makes it really difficult for you to find your creativity and your growth in managing your product.

I think succinctly, it’s like having a manager is going to give you the space to go off by yourself. I think the second part is giving you the visibility and credit where you want to be successful. What we mean by that is that my parallel in the military it’s like, you want to give the credit down to the lowest level.

Ultimately I didn’t write a line of code that we shipped. It’s always to the credit of team that work on this stuff, like here’s what’s going on. I think managers who can recognize it’s a team effort, yes, I’m doing critical meetings, I’m coordinating, I’m communicating out all these various things. But I’m actually doing all that in the service of my team so they can actually be successful.

I think managers that can recognize that and do that same thing. I think that’s helpful because I think ultimately, it’s never good when someone’s like, “I did all this work.” “You did it yourself?”

Devani: And they’re just looking like, “You can’t write a single line.”

Eason: I think that’s the big things in my mind.

McCue: One thing is I think is that product management is a hard function to be a manager in, because you’re wearing two hats. One hat is the strategy piece. You’re communicating with the execs and trying to say what are you working on and why? And how is that going? And then there’s the other piece of you’re trying to nurture this person’s career and development.

And I would say, so far what I’ve seen in product management is more of the former. There’s a lot of that great advice about strategy and what you’re working on and how to think about stuff.

I think people management side is a little bit less focused on in product management. It’s kind of like you get help in it. Obviously, you’re getting advice. But I think the strategy piece is such an important part of managing product managers that sometimes the people management piece can fall a little bit by the wayside. Not everywhere, but…

Eason: I can say from Google, I think it’s evolved to where it’s like, they’re very intentional. We want people to do as much product management as they can do in order to contribute as much as possible and not burden the management.

Some people may not actually want to be people managers. It’s not like everyone excited about doing that. Even in the engineering team, some engineers really love just being engineers. To tell them to manage engineers, they’re like, I don’t want to do this thing.

I think you also don’t want to force people. If it’s not right for you, then you can accelerate in just being a great manager of the product, not necessarily of people. I think they made it easy for you to choose that. You don’t have to do that to be successful in the company.

McCue: I would love to see more of people management in the product management. Maybe that’s coming from the military and just seeing how important it is for us to take care of the people we work with. That’s just so ingrained.

I think a good product manager would take the time to create systems or take the time to really make sure that they’re nurturing on the people side as well if possible, which is hard.

Devani: Yeah, the lesser thought of skill or practice. Before we wrap up, a couple of quick questions for you. What is your favorite piece of software that you use as a product manager? You can’t say Slack.

Eason: I can’t say Google products? They’re everywhere.

Devani: Do you guys use other products? You have your own internal products and you can build stuff very quickly.

Eason: Surprisingly, most things we build ourselves. “Oh, this is a problem? Let’s just build it.” It’s rare. But I think it’s good because employees are… I use a lot of Google products and if I don’t like something, I’ll just go to the product manager’s desk like, “This isn’t working.” I can file the bug to them. If you’re not using your own product, I think you’re missing out the experience.

McCue: I have a couple in mind, but they’re all very recency biased. One I love usertesting.com. I was amazed when I first found it. We had a regular rolling research testing that we did, but it took a long time to get participants and bring them in. And then there’s this magical website that let you put things in front of people, create a task, and then the next day, you have 5 to 10 participants who have given you feedback. That was just mind-blowing for me, so shout-out to usertesting.com.

Also, I love Mural. We have a lot of people who are remote, and Mural is basically like a sticky note app. I’m sure they’ll hate that description.

Instead of being in a room putting up sticky notes you can just make sticky notes on the board on the computer. You can drag them around and do dot voting right there. It just speeds up the brainstorming process and allows the remote people to be involved rather than pointing the camera at the whiteboard where all the sticky notes are and you need to take them off afterwards. I really have enjoyed using Mural. I used it yesterday. I was just thinking about it.

Devani: We’ll give you a pass Jamal, since you have all these internal tools. What is a resource, like a book or an article, something you’ve read recently that really popped out in your mind, that gave you a new dimension or a new way of thinking or perspective about product management, about what you do every day? And maybe not just product management, just about what you do every day and how to do it.

Eason: There’s this book that just came out, “The Billionaire Coach”. What’s interesting about it is it’s actually written by the mentees of a coach who mentored a lot of the CEOs in Silicon Valley.

I think it’s interesting, because there’s this aspect of coaching that I think you need at all levels. You’re thinking about sports. An athlete is getting coached all the time. Michael Jordan, or any athlete, they’re being coached all the time. But in the professional world, it’s like you just kind of go by yourself and I’m assuming they’ll figure it out.

I think that inspired me to think about how my coaching, how am I helping my team and employees, and how do I seek out coaching as well. Because you can kind of get bogged down by your day to day work, but you’re not in your A-game at all times and you might need a third person perspective to say, “This isn’t going well.”

And sometimes your manager may or may not be able to give you that advice but some of you have no vested interest except your success can be there. I think that was a good book and resource to look at.

Devani: Awesome, “The Billionaire Coach”?

Eason: Yes.

McCue: I’m going to do a pass.

Devani: No worries. That brings us to the end of today. Jamal and Lorilyn, thank you for joining us. This has been the product management version of The Operators, and thank you everyone for joining us.

Eason: Thank you.

McCue: Thanks.